In step with the sensationalist reporting of the 1920s tabloids, it was conceivably the Omaha newshawks who gave The River Girl her haunting name. Despite that, it wasn’t all provocative paper selling. Although limited to her death and where her dismembered body parts were discovered, The River Girl epithet was a somber, accurate depiction of her fateful casting. A simple name, she might have been called this by the poor boys who discovered her remains or the nearby neighbors forced to recall every odd bump and bang in the preceding nights. Omaha’s introduction to The River Girl, the events that followed and a whole host of characters who were thrust into the light captured my attention years ago and though I could never hope to solve her mystery, I held vigil. The murder victim is unknown to this day. This is my examination of the events.

Be apprised, tonight’s dark investigation might be unsettling to some readers. I have limited the quotes taken directly from newspapers of the times, which were quite explicit and could be unapologetically gruesome, but I did include those that illuminate an honest depiction of the scene and months to follow. There are no graphic images or photographs, I promise you that, but sometimes descript phrases can linger in the mind. Please read on with this awareness. If historic crime is not your cup of tea, we will plan to see you at our next investigation.

“Ladies and gentlemen, our My Omaha Obsession investigation is sponsored by Camel Turkish and Domestic Blend Cigarettes. Always Just the Right Note. So many things are not quite right in this perplexing world, that a touch of authority is actually refreshing…And this is why people of sensitive taste hold fast to Camels. That perfect blend strikes just the right note in the scale of cigarette enjoyment.”

The Paper on the Porch

On the Monday morning of October 5, 1925 Omaha awoke to news of an unknown murdered girl discovered over the weekend on the muddy riverbanks of the Missouri. There had not been a story like it since wild wolves had ripped apart the unnamed “Mystery Girl” years earlier and left her near the Washington highway. The Omaha Daily Bee and the Omaha World-Herald were not only the first papers to press but their reporters were potentially the first people up and down the riverbank looking for “clews,*” surely contaminating the whole crime scene–this, in absence of the authorities who purportedly announced they would not be taking up the curious case over boundary disputes. Various police and sheriff departments would become involved over time. Let’s start at the top.

*This murder took place in a time when local reporters used the word clew, instead of clue, hinting at a folkloric ball of thread that guides one out of a maze. It was this motif, based in myth, that seemed to fit The River Girl case all too perfectly, in my estimation, as the case wore on.

“River Gives Up Severed Body of Girl.” Omaha Daily Bee Monday, October 5, 1925.

“Head, 3 Limbs Missing…With only the dismembered fragments of a young woman’s body as clues to one of the most gruesome murder mysteries uncovered in Omaha in years, Omaha and Council Bluffs police and sheriff’s officers are seeking a degenerate fiend who is believed to have murdered the young woman, severed the head and limbs and torso with a saw and thrown the dismembered body into the Missouri river, north of Florence.”

Searching for an obvious degenerate fiend might have been their first mistake or that may have been sensational writing aimed to pique the curious. On Saturday, October 3, two boys were out hunting on the Iowa side of the river, two blocks north of the Illinois Central bridge and found the lower part of a woman’s torso. Then on Sunday morning, October 4th a farm boy found a right leg also on the Iowa side of the river; concurrently two other boys found the upper part of a female torso on the Nebraska side, six miles north of Florence.

Daily Bee: “Dr. Samuel McCleneghan, coroner’s physician, said that the body was apparently that of a woman about 18 to 22 years, weighing about 110 pounds. There were no parts of the body found which could serve for identification. Dr. McCleneghan said that the body had unquestionably been mutilated with a saw. Police are virtually certain that the young woman was probably murdered at some house in Omaha, that the murderer then mutilated the body to prevent recognition, and carried the gruesome remains to the spot north of Florence to throw the evidence of the crime in the river.” Deputy Dan Phillips would “continue the search up and down the river bank and that the Iowa side is also being subjected to minute search for clues.”

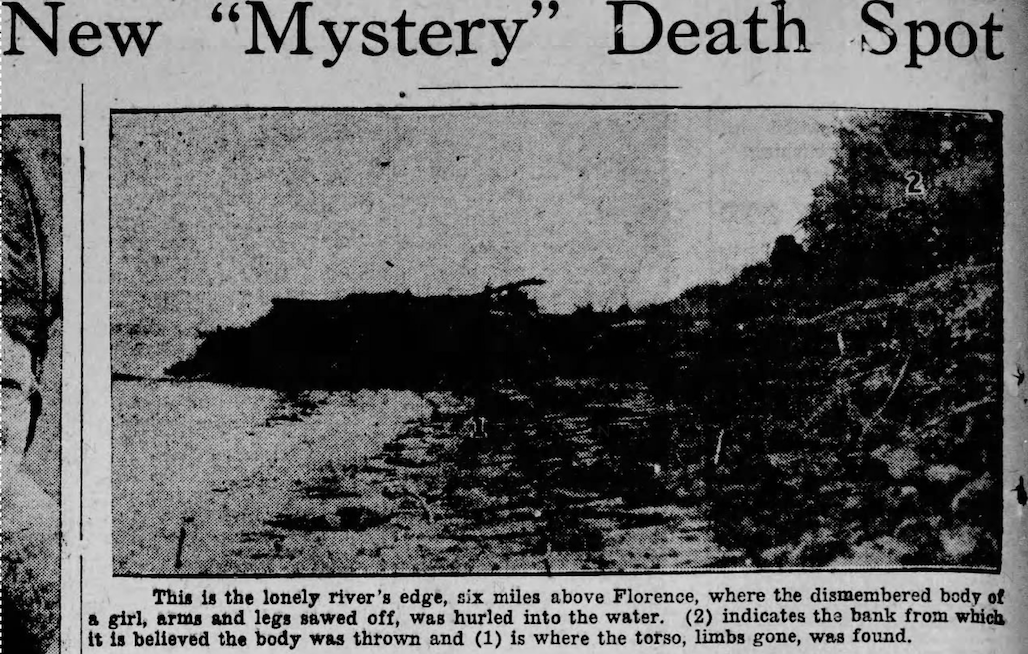

“The spot north of Florence where the lower part of the torso was found is only a few yards from a branch in the road, one branch turning to the left to climb the bank and the other descending along the banks of the river. From this lower road a 25 foot bank descends almost to the edge of the river. It was at the foot of this bank, only a few feet from water that the upper part of the torso was found. Investigators believe that the murderer drove to the crossroads and from there threw the parts of the body into the river, hoping that all trace of the murder would quickly be lost. The head and limbs could easily be thrown into the river from the lower road but the heavier torso, it is supposed, could not be thrown so far and fell on the bank, rolling almost to the water’s edge. The murderer left, it is supposed, believing that all of the body had been cast into the muddy waters of the river. This probably occurred about a week ago.”

As to why it was believed the crime was committed in an Omaha house was not made clear.

“Dismembered, Body of Girl Found in River.” Omaha Evening World-Herald October 5, 1925.

Not to be outscooped, by the time of Monday evening’s World-Herald printing on October 5, 1925, the plot line had developed new conflicts. The woman’s remains found on the Nebraska side of the Missouri River were taken to Hulse and Riepen’s morgue. “The other parts of the body are held at Cutler’s morgue in Council Bluffs. Sheriff Endres said he had a deputy working the case Sunday (Oct 4) but had withdrawn him today, 5th. ‘The body was found in Washington County,’ he said, ‘and the authorities at Blair should do the investigating.'” (Jurisdiction issues were beginning in the confusion of remains being found in different counties and states.) “Omaha police also are not working on the mystery. A search up and down the river bank by newspaper men today revealed nothing to lend a clue to the mystery.” (A potentially contaminated scene in the madness.) “The spot where the hacked body was tossed to the river is near a road, frequented a great deal by booze parties, according to residents of the neighborhood. J. W. Snodderly, whose home is but a short distance away said today he had heard two revolver shots about 8 o’clock Thursday or Friday. Shots at that hour, he said, are unusual.” (What time were revolver shots usual in the area, I wondered.) “Revolver shots also were heard in the vicinity about a week ago by J. H. Kolle, who lives near the Ponca School. He said he was awakened at 2 am by shooting and shortly afterwards a car sped north past his house. It was on a road which would lead to the river.”

“The flesh of all the parts was firm, fair and pink. The torso bled freely when it was moved. The head had been sawed off from behind. The left arm had been sawed part way and twisted off. The right arm had been sawed off cleanly. The legs had been sawed off at the hips.” I concluded from this The River Girl was Caucasian. This detailed account presumably from Dr. Samuel McCleneghan or was it Sheriff Enders?

Cars parked along a curve in a road near the Missouri River. Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). The Durham Museum. 1926.

Within days the Omaha World-Herald would coin the unidentified murder victim The River Girl. The Omaha Daily Bee would label the unknown perpetrator or perpetrators The Saw Killer.

The Professionals

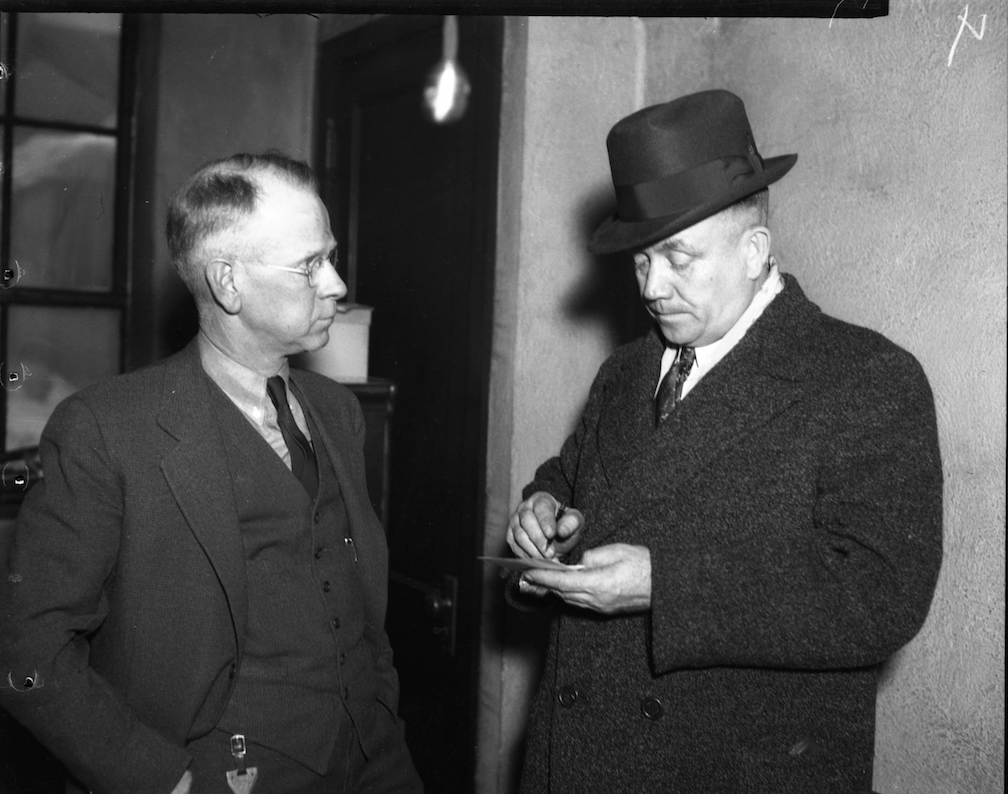

Image borrowed from the Morning World-Herald. August 1, 1923.

Hulse & Riepen Undertakers were considered Omaha pioneer funeral directors. Their business was located on 701 South 16th Street, later moved to their 23rd and Cuming Street operation by the time of The River Girl case. By October 5, the woman’s remains found on the Nebraska side of the Missouri River were taken to Hulse and Riepen’s morgue. Oddly the other parts of the body were held at Cutler’s morgue in Council Bluffs, Iowa. The Hulse and Riepen Undertakers involvement in The River Girl case would be ongoing.

I found Dr. Samuel McCleneghan employed as the coroner’s physician as early as 1911, possibly earlier. He would be called back into The River Girl case a number of times. “Dr. Sam” Richard McCleneghan was born in 1890, a 1907 graduate of Creighton University. In addition to his work as the Douglas County coroner’s physician, of his 50 years of medical practice, Dr. Samuel McCleneghan served as head of the obstetrics department at Doctor’s Hospital, he served as Union Pacific’s doctor, the Douglas County coroner’s physician, clinical professor of Creighton and a staff member of St. Joseph’s Hospital. A longtime, well known Omaha physician, Dr. Sam McClenegan died at the age of 93 in 1974.

Cat T. Braasch shared this image of Dr. Sam McCleneghan and Mrs. McCleneghan from 1951.

Michael Lawrence “Mike” Endres immigrated to the United States from Bavaria, Germany in 1890, arriving in Omaha by 1898. His wife, Charlotte Rydell Endres was a Swedish immigrant. In his early Omaha years Endres had a contracting business as well as a wallpaper, paint, oil and glass store up on Ames Avenue until 1917 when he was elected County and City Treasurer. At the time of The River Girl mystery, Mike Endres was fifty years old and had been elected Sheriff of Douglas County just three years prior. He was not particularly popular with a portion of the good community when he initiated his first step to ending gambling in Omaha. He would work to outlaw the games in pool halls and cigar stores. He only served as Sheriff until 1927. I share these things in part as explanation to some of the early decisions in The River Girl mystery.

Omaha Daily Bee Newspaper, 1923.

The Omaha Boys

On Sunday morning, October 4th, William Stohlman 18, 5528 North 27th Street and Roy Dahl, 18, 3066 Ernst Street, were up early to go hunting north of Florence. As this was said to be in the Washington County area, I wondered if they were near Fort Calhoun or Blair. I imagined this was possibly a spot that the boys knew and had hunted previously. The quiet and stillness of the riverbank was in my mind. Apparently the two followed the lower road at the branch off and almost stumbled over part of the body. “Without touching the body,” the boys hurried home and told Stohlman’s parents of the discovery. Police and the sheriff were notified and sent investigators. They searched the river bank for miles above and below the spot but found no more of the body.

Young William Stohlman’s family home at 5528 North 27th Street where the boys returned with the ghastly report was built in 1919. Later William Randolph Stohlman joined the U. S. Army where he served as a combat veteran in both World War II and the Korean War. He returned to the States in 1952. I did not find in my search that he ever married or had children, but would certainly like to know any family details if anyone cares to share. William Stohlman died in 1961 at the age of 55, still living in this house, his boyhood home.

William’s pal, young Roy Frederick Dahl, had become a deputy sheriff by 1938. He was tasked early in his career with solving a murder-suicide between a bride and groom wedded just nine days. It struck me that both William and Roy were witness to the horrors of this world at such a young age but I can only guess the impact, as these things are different for everyone. Finding The River Girl was just a glimpse into the traumatic events that they must have endured throughout their lives.

The Dahl parents, Fred and Anna, were Swedish immigrants. Mr. Fred E. Dahl worked as a tailor for a clothing store. A strange coincidence, which served as a foreshadowing into my own investigation of The River Girl, is that father Fred E. Dahl would report his wife Anna missing in 1937 long after she had “disappeared” three months earlier. Supposedly Mrs. Dahl left Omaha to visit relatives in Western Iowa but when he didn’t hear from her, Mr. Dahl wrote to the relatives and found his wife had never arrived. This was at a time when only about half the American homes had telephones. I would find through an ancestry site that Anna Dahl, his wife, died in 1964. The 1940 United States Census logged the Dahl couple living together again with their two daughters, Ruth and Jane. Roy was working as deputy sheriff by then and out of the house with his own family. So maybe Mrs. Dahl was just in hiding or having a long, solo vacation in 1937. Strangely I would find a lot of women missing and in hiding during this time period of underutilized telephones and sparingly-used postal addresses.

While William and Roy made their miserable discovery known, the right leg of the body was found about the same time Sunday morning by a “farmer boy living near Council Bluffs.” It was first reported as the “left leg” but that changed shortly after first reporting. The unnamed farm boy found the limb washed up onto the bank, several miles below the spot where the upper part of the torso was found and on the opposite side of the river. The lower part of the torso had been found floating Saturday (Oct 3) by Alden Head, 14, 1020 North 32nd Street, Council Bluffs, who was hunting along the river near the Illinois Central bridge. The body was found floating in a backwash of the river. If you fine sleuths are tracking this like I am, you have noted a change in the storyline. This is common. Initially they had reported there were “two boys were out hunting on the Iowa side of the river, two blocks north of the Illinois Central bridge and found the lower part of a woman’s torso.” Ultimately changed to one boy–Alden Head.

Another boy was tracked down by the authorities, as he provided an apparent timeline that they found useful. “William Boone, 14, of Florence, who was found by investigators fishing near the crossroads above Florence, told police that he had passed that spot nearly every day for two weeks, and seen the mutilated portion of the body lying there for the past four or five days. He said that he had not examined it closely and had believed that it was the body of a dog or cat washed up by the river. His statement and the condition of the parts of the body, which was badly decomposed, leads investigators to believe that the murder took place at least a week ago.” It is unclear to me what portion of the body William Boone saw near the crossroads above Florence.

Looking northeast from Central High School at the area north of Capitol Avenue. The air is hazy with smoke in this image. A combination of homes, apartments aand businesses. Along the river’s edge are the Union Pacific shops. You can see the Loose-Wilkes Biscuit Co. just below them. In the background is the Illinois Central Missouri River Bridge, a rail through truss double swing bridge spanning the Missouri River. Just a slight distance the east of this bridge is where The River Girl’s lower torso was found floating by Alden Head of Council Bluffs. The bridge is currently owned by the Canadian National Railway and was closed in 1980. Also known as the IC Bridge or the East Omaha Bridge a portion is kept swung open to allow for passage on the river. In my day we just called this the old train bridge and people would jump off of it. Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). The Durham Museum. May of 1911.

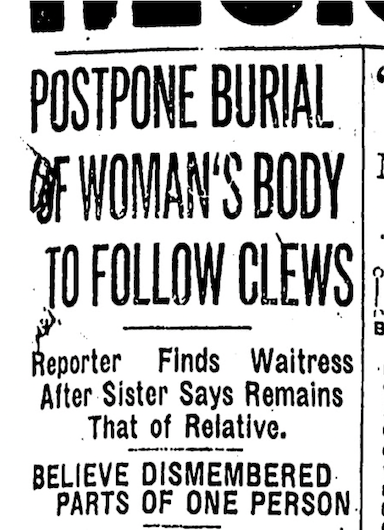

Postpone Burial of Woman’s Body to Follow Clews. October 6, 1925. OWH.

A burial for The River Girl was being planned by Hulse and Riepen Undertakers but understandably they wanted to wait as long as possible to hopefully identify the young miss. “The dismembered parts were matched yesterday and officers said it convinced them that they were all of the same body.” Examination of said parts established that the woman was a blonde, presumably about 120 to 140 pound and between the ages of 18-23. Although they didn’t say, the woman was Caucasian. The body had evidently been sawed into four sections, in addition to the sawing off of the arms. The head was still missing.

Again burial was postponed when “a theory was advanced” in light of information brought forward by a Mr. C. S. Webber of the Rees Printing Company. Mr. Webber said that the previous Wednesday he “saw the torso of a body floating more than 150 yards north of the place where it was found.” The idea being that the body had been thrown into the river “farther north of where it was first believed by authorities to have been tossed.”

A view of the Missouri River from a hill. Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). The Durham Museum. 1926.

There were marks on The River Girl’s back, suspicioned as the result of being thrown from the high cliff to the river bank. The officials were certain that the killer committed his crime in a house in Omaha, “calmly sawed the body to bits, then drove to the high bluffs and hurled it, bit by bit, into the river—but that one piece proved too heavy to hurl so far and laid on the bank for several days.”

Jurisdiction Dispute

The cast of characters that I would find connected to this case were as follows: Douglas County Sheriff M. L. Endres and Deputy Sheriff Dan Phillips. Washington County Attorney’s Investigator Harvey Sautter; Washington County Coroner Steinwender; County Attorney Reed O’Hanlon of Blair; Washington County Sheriff Morris Mehrens.

Generally speaking, the agency where a body is discovered investigates the murder and those lines are very clear. The River Girl investigation became complicated because both jurisdictions were within Nebraska as well as Iowa. Whether or not the scene where the second part of the torso was found was in Douglas County or in Washington County became the very public dispute. “If it were in Washington County, it was not an eighth of mile over the line.” This hinted at The River Girl being found in the Fort Calhoun area, which I linked back to the previous “booze parties” comment. We know from our earlier investigations of the wild and wooly Fort Calhoun road houses and “country clubs” during Prohibition. For their part, Washington County was willing to defray the expense of The River Girl burial but indicated “the burden of responsibility for solving the mystery” was on Douglas County. County Attorney Reed O’Hanlon of Blair professed the body should be buried in Douglas County, because his examination of the scene convinced him that the crime was committed in Douglas County and if persecution was to materialize in the future, it would be in Douglas County. He stated Washington County would cooperate as much as they could but only after he made plain that there were no missing women from Washington County. Sheriff Endres was reluctant to assume the responsibility for the case but said Douglas County would investigate. He said, “As yet, I am without a clew.” No truer words were spoken on that day. Council Bluffs authorities relinquished their part in the case when they turned over the limb and portion of The River Girl torso to Hulse and Riepen Undertakers in Omaha.

Deputy Sherriff Dan Phillips of Douglas County would take up as The River Girl lead from there on out.

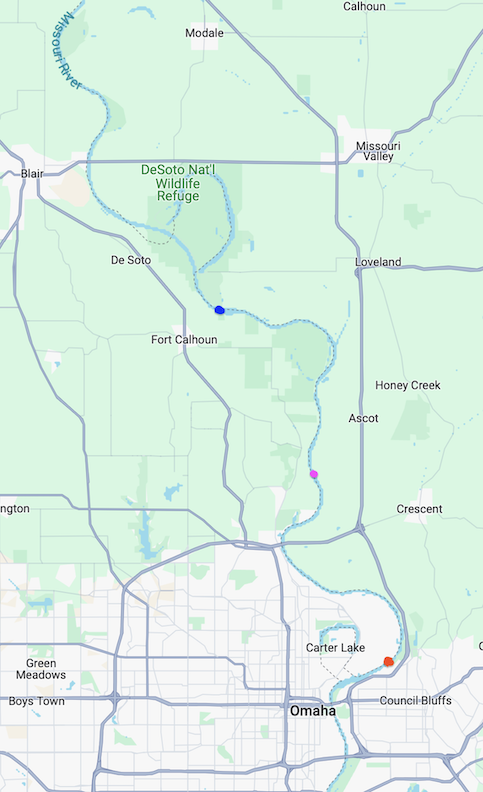

Map image by Google Map.

Red dot denotes where Alden Head found the lower torso on October 3, Iowa side, near the train bridge.

Blue dot approximately where The River Girl upper torso was found October 4, in Washington County, Nebraska side– said to be just over the county line.

Pink dot is my guesstimate where on October 4, the unnamed farm boy found The River Girl’s right leg on the Iowa side. Reported to be miles from the Washington County site, but north of the Oct 3rd discovery.

Studying this map, it is hard to understand why the authorities were so sure that The River Girl was killed in an Omaha house. I do understand why they believe the first of her remains were unsuccessfully dumped in Washington County.

The Dirty Side of Omaha

The investigation into the mid-1920s Omaha is one shrouded in deep veils of mystery. There were transparent layers, which most people at the time could see and were able to discuss. These are the layers that an amateur detective decades later is able to track. But there was and is so much more that I, and perhaps you, will never be able to truly see or comprehend. I have compiled some of the obvious social concerns of 1925. When I share my findings about the perceived changing of society and underworld culture in Omaha, it is not to blame The River Girl or cast her in this underbelly light as some willing (or otherwise) participant. On a very foundational level we know The River Girl came across a violent person or persons from this area or passing through. My suspicions are that The Saw Killer was from this area.

Downtown dance hall. Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). The Durham Museum. 1928

Very near the time of The River Girl’s death, “law and order Sundays” were being installed from the churches’ pulpits to curb a recent crime wave or what they were calling the jazz-mad age. Omahans voiced concern over the startling increase in murders, robberies and many other serious crimes. From what I found, there was evidence that this was a nationwide scare, trickling down to Omaha, because the Omaha Police and occasionally the press would come out exposing low crime numbers for the city. Was this some sort of targeted Safe and Good Omaha campaign? A case such as Guy Parker, 17, who was in critical condition at Lord Lister hospital from a revolver bullet lodged near his heart when a man he was attempting to rob, in turn shot him, roused local community leaders to their own campaign. Juveniles and young men and women were under attack for their “Jazzing along the doubtful path to destruction.” High school parties were marked for their heavy drinking seemingly “accepted by the very best families” who had also become negligent in their heavy partying ways. “Damage has been done to furniture in hotels and the drunken youth have reeled from the ballrooms in the small hours of the mornings.” To read the overview, there were an endless string of crimes in all descriptions. Other proclaimed the United States the most lawless civilized nation on Earth. “Homicides are up.” Interviews with the local Welfare Board staff had a tone: “I can’t understand how a mother or father can be so absolutely silly as to let a daughter of 14 or 15 go to a public dance hall, right into the jaws of temptation where lewd males often lie in wait like spiders for their insolent and ignorant prey.” Dance halls and pool rooms were thought the breeding ground. “Crime immorality and depravity are born and cradled in Omaha dance halls. These are the schools of the underworld. In them the lowest class of men search for their prey among girls just entering their teens.”

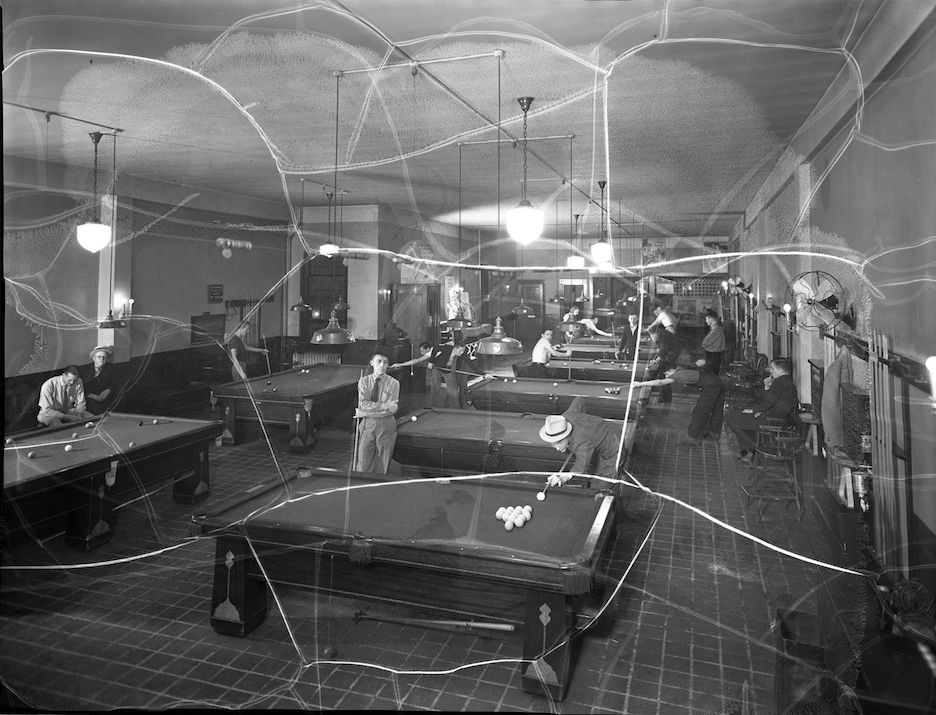

Downtown pool hall. Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972).

There were hints of larger but hidden systems working beneath the Welfare Board’s view. Months before The River Girl was found, federal prohibition agents started a nationwide search for Frank L. Peterson, Omaha manager of an alcohol distributer, the Rossville company who had disappeared from Omaha January 21. Prohibition agents had discovered a shortage of over 5,000 gallons of alcohol from the Rossville Company. As manager of the agency, Peterson had distribution of alcohol for Nebraska, Colorado, Iowa and Missouri.

16th Street. United Cigar. Mercedes Cigar. Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972).

There were unseen killings in the bootleggers’ war between rival gangs. The Omaha Police had their publicized raiding squads but there was also open discussion of the OPD turning a blind eye. It was common knowledge that the king of the underworld operated in the downtown district, less than two squares from the corner of 16th and Harney, an open gambling house. During the summer of 1925 the newspapers carried a story to the effect that the sheriff visited the place and “saw nothing more than a few innocent games of pinochle.” As a local wrote in to the papers: “Right today I can take a fifteen-minute walk in the downtown district and along this route I can show anyone fourteen houses of prostitution, four bootleg joints and six gambling places—all of the above are running open. These places have all been running a long time. Law enforcement should have made a fight against these places long ago.” Meanwhile at the same time The River Girl was being discovered in this area,“100 white girls” were found in a raid of New York City’s underworld, hidden within Chinatown but the girls didn’t want to leave.

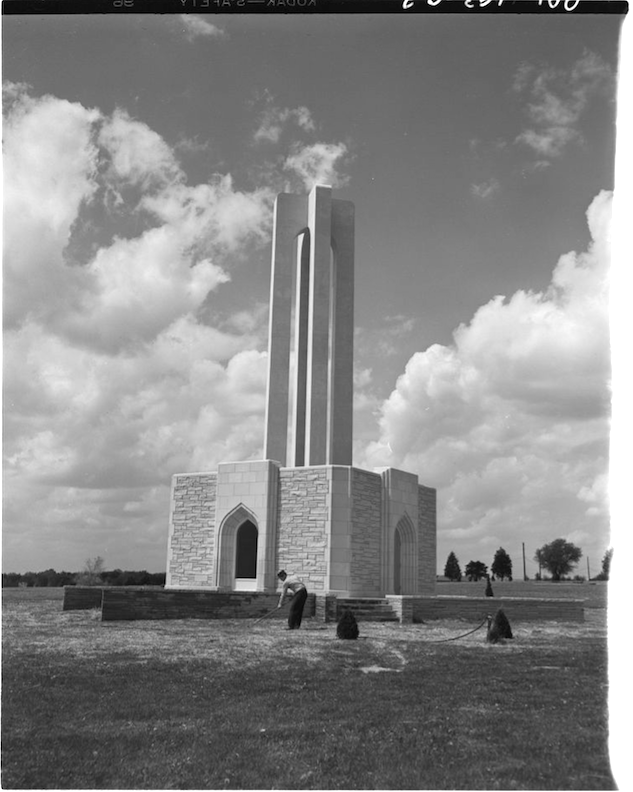

Funeral for The River Girl

When they had gathered as much of the The River Girl remains as they could to date, there was obvious social concern about protocol and interring her body in a timely manner. The River Girl was buried in the Evergreen Cemetery, in a plot donated by the Hulse & Riepen Undertakers. Evergreen Memorial Park, as it is called now, was privately founded in 1872 and is located at 76th and Center Streets (2300 South 78th Street.) The opening and closing of the grave is a significant funeral ritual– a symbolic passage to the hereafter, in many culture’s beliefs. An actual funeral was held and a grave designated “with the inscription ‘The River Girl.’” This clue would have me walking in the rain up at the beautiful Evergreen for hours. More on that later.

On the left: October 8, 1925. Omaha Evening World Herald. On the right: October 9, 1925. Omaha Evening Bee.

What I hadn’t imagined when I began following the leads of The River Girl case was the amount of missing women from small towns and those who didn’t want to be found in Omaha.

Missing in Omaha

Mrs. Clifford Corbin was recovering from an operation at the St. Joseph’s hospital when she sat up and made a public declaration—the dismembered body was “that of my sister, Mrs. Estelle Plumley, who has been missing nearly two weeks.” The reason Mrs. Corbin determined The River Girl was her sister was that her sister had not been to visit at her hospital bed and the description fit Estelle Plumley. Mrs. Plumley of Ralston, Iowa’s husband, Ray P. Plumley reported her missing on September 14 and that “she probably was in Omaha. She may have used the name of Peggy Hener.” To the credit of the Omaha World-Herald reporter, Mrs. Estelle Plumley was found after merely a half hour search, quietly working as a waitress at the Boston Restaurant at 15th and Dodge Streets. Upon finding Mrs. Plumley she was described as a 28 year old blonde; 140 pounds and five feet two. Unassuming and surely not communicating with her family, did Estelle Plumley cut off contact? In response to finding Mrs. Plumley, the sister strangely said, “Mrs. Plumley left him and he knew where she was at the present time.” This might suggest that Mrs. Corbin feared that her brother in law was capable of murder. Or at the end of the day, did the sister very publicly just want a hospital visit from her sister?

The authorities and press were then attempting to establish whether the victim was Mrs. Hans Shockley of Ames, Iowa. Mysteriously “she disappeared from Mondamin, Iowa while she and her husband were motoring through the town on July 18. (…) The best means of identification in the absence of the heard, is a scar on Mrs. Shockley’s left leg, the sheriff said. “She was in a delicate condition when she dropped from sight, while Dr. S. McCleneghan, who performed the autopsy on the body, does not believe the River Girl was. Mrs. Shockley was 22, about 5 feet 7 inches tall and weighed approximately 110 pounds.” I found later writing that said, “he believed the murder victim probably was not Mrs. Shockley because the murder victim apparently had not been in a delicate condition.” (This is an old-fashioned euphemism meaning a woman was pregnant.) This manhunt led to the discovery that Mrs. Shockley was alive and well and in Omaha. On the face of it, pregnant or having given birth and hiding from her husband? If my math adds up, the young miss who moved to Omaha was Leah Anna Johnson Shockley. I discovered her son, Kenneth Eugene Shockley was indeed born in September of 1925 in Omaha. By the time of the 1930 Census, however, Charles “Hans” Shockley and Leah Johnson Shockley had reunited and were living with their four children back in Ames, Iowa.

George Buehler’s Discovery and First Exhumation

October 15, 1925. Omaha Evening World-Herald.

On October 15th the Omaha World-Herald and the Omaha Daily News announced that the left arm of The River Girl was discovered on October 14th by George Buehler, employee of the Woods Brothers Construction company, out of Lincoln, Nebraska. The arm was found near a retard (to protect the bank from erosion) being built for the waterworks, three miles above Florence. It was noted there was no jewelry, scars or marks which might lead to identification. “It was found three miles down the river, on the Iowa side from where the upper part of the torso was found and about the same distance above where the lower portion was located. (…) The limb had been sawed off just below the shoulder joint and in spite of the fact that it apparently had been in the water for some time, it was in fairly good state of preservation.”

Within a few months, George Buehler was involved in a number of river misfortunes. Buehler was watchman of “Elisha Wood” moored in the Missouri river at Bellevue for the winter. (The Elisha Wood, later discovered to be a two hundred ton steamboat, named the Eliza Woods, belonged to the Woods Brothers Construction company. It was named after Colonel Woods’ wife. The Woods’ steamboat had hefty contracts for up and down the river for protection work.) One night, a 24-year-old soda fountain clerk, Leo Patrick Hanley and friends were messing around, throwing bricks into the ice when Hanley drowned after slipping off the barge. In a later telling of the event by young shoe salesman, George Jarman, it was just the two of them at the river. Let me see if I can explain this. The young men allegedly roped bricks to their waists in order to keep hold of the bricks as they repeatedly threw them at the icy river. Jarman stated one of the brick’s weight and thrust pulled Hanley into the frozen river. Jarman offered to throw Hanley a rope but Hanley was said to have yelled back, “I can swim.” Then he suddenly disappeared in the blackness. Jarman drove through the night to the Buehler house to alert the no doubt horrified family. It was all so odd. George Buehler was then tasked with taking out the Elisha Wood boat to recover Hanley’s body, unfortunately, never found. Tragically, a group of friends were witness to 19 year old George Jarman’s drowning in a sand pit the very next summer. The in-progress mystery helped lend some clues. A year later, at age 32, George Buehler was listed as “pilot of the steamboat Eliza Woods.” The boat’s fireman, Frank Vannorman, 19 was servicing the boat when he was injured and fell into the swift current of the Missouri, while unconscious. Buehler jumped in and saved his fellow boatman. The Eliza Woods had been “stationed recently on construction work near the Illinois Central bridge.” Months later the Eliza Woods capsized in the Missouri River near Atherton, Missouri, when the boat encountered a sharp wind and was driven against the retards being placed in the river near the east bank. Two people died and fifteen people were rescued from the overturned steamer or swam to safety.

The Case for the Missing Fremont Girl and Second Exhumation

27 year old, Fremont coal driver, Fred Oliver came forward and reported to Sheriff Johnson of Dodge County, he was “positive that it is the body of his wife,” from whom he has been separated for a year. Mrs. Edna Oliver was a blonde, 24 years old, weighing 140 pounds, had three children and was said to be living in Omaha with another man. That man was being sought for questioning. Florence Fontenelle and Minne Lusa Review reported on the growing pressure from the Fremont woman’s family. Sheriff W. A. Johnson of Fremont was predicted to soon ask that The River Girl’s body be exhumed. Mr. Oliver had The River Girl exhumed on a late Friday, October 16, from her Evergreen grave in the presence of Oliver and officials of Douglas, Dodge and Washington counties. Oliver proclaimed that the scar on the torso of the body, made by abscesses, was identical to his wife’ body. (He had to use a large magnifying glass to find them.) Acting on Mr. Oliver’s statement, the officials of the three counties searched along the Iowa and Nebraska banks of the river in hopes of finding The River Girl’s head. Washington County Attorney Reed O’Hanlon was dubious of the Mr. Oliver’s identification. His questioning came from the fact that the scars on The River Girl “were tiny”—so small that Hulse & Ripen did not even make note of them in their preparation of the body.

On the left October 17, 1925. Omaha World-Herald. On the right: Oct 18, 1925. Omaha Daily Bee.

Edna Oliver left the Fremont home of her father, Andrew Christofferson on September 8 (some accounts say the 9th) to live with an Omaha coalheaver, Ed Moore, “who had been paying her attentions.” After Mrs. Oliver and Ed Moore left for Omaha, they had not been heard from since. That man was being sought by Sheriff Mehrens of Blair for aid in solving the disappearance of the woman. (Why Blair?) Oliver said he and his wife were separated and she had planned to divorce him.

Mrs. Oliver was said to have worked as a charwoman at a hospital. When I followed that lead, it appeared that back in January of 1925, Edna Oliver had moved into the St. Joseph’s hospital in Omaha “for care and shelter until her baby was born.” On March 12 she left the hospital without permission and failed to return. The hospital shared with the newsmen that Mrs. Oliver related that her “husband had deserted” her. She was given light employment within the hospital, sewing and work in the kitchen. She was reprimanded for breaking hospital rules, which forbade her to go out nights, a rule she continued to break.

West entrance to St. Joseph’s Hospital on 10th and Martha Street. Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). The Durham Museum. 1926.

It was later revealed that Ed Moore was known to beat Mrs. Oliver and had knocked her down on several occasions. “It is because they fought so much that she left him for a while.” The pursuit of Mrs. Fred Oliver became more problematic when it was learned prior to her disappearance from Fremont, she “had figured in a sensational incident in which she charged three men with kidnapping her and driving her to a lonely spot in Saunders county.” The matter was dropped by the Saunders County attorney because of lack of evidence. Later it was reported threats of violence were directed against Mrs. Oliver and certain Fremont officials. (Who threatened and how was this communicated?) Later still it was revealed that in May of 1925, Mrs. Oliver sued her husband for divorce, alleging cruelty. The day before she disappeared, she had buried her two-month-old baby. Of the three living children, the oldest was only five. One son was living with her father, Mr. Christofferson in Fremont; the other two children had been placed in an Omaha institution the previous spring. I wondered if this was Saint James Orphanage? All of this hinted at a very complex set of stressors, potential mental health issues, lack of resources and true tragedies–possibly insurmountable for a young woman.

Just to give an idea of the old 10th Street. Sam Raiss’s rooming house would have been a bit south of this. Looking straight north on 10th Street from Jackson Street. On the right is the old Wright & Wilhelm Hardware warehouse. Across the street is the old Windsor Hotel. There are cars and streetcars going down the street. Circa. 1930. Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). Durham Museum.

Deputy Sheriff Dan Phillips headed a search party which visited “more than fifty cheap rooming houses and hotels” to search for Edna Oliver and Ed Moore. They were reported to have left the rooming house of Sam Raiss, 504 ½ South 10th Street. According to Raise, the woman said to him, “Haven’t you seen in the newspapers where they are looking for me?” She had borrowed two dollars from Mr. Raiss on Saturday, stating that her sister was ill back in Fremont. When Mrs. Oliver left the next day, Raiss was of the belief that she’d gone to her sister’s side. Ed Moore checked out later in the morning. But when the sheriff checked in with the sister she was not ill and had not been in communication with Edna.

The Real Mrs. Fred Oliver and New Efforts

As if there wasn’t proof enough that Edna Christofferson Oliver was alive, Coroner’s Physician McCleneghan came forward with his evidence. His examination of “the river body” determined “the woman had not given birth to a baby within four months and probably not within six months, if ever.” When Mrs. Oliver disappeared from Fremont the day after burying her infant. Sheriff Johnson of Fremont’s theory was that Mrs. Oliver, upon reading that the body was identified as hers, fled to further forestall being found in the company of Ed Moore. Deputy Sheriff Dan Phillips confessed that he was baffled by the conflicting circumstances all around. Interestingly Phillips divulged many people had called him with clues. These tipsters all refused to give their names. “They insisted they are sure this must be the body of some woman whom they know to be missing.” When Phillips asked them to come in, they refused or if they did make appointments, they failed to keep them.

A photograph of Mrs. Oliver was positively identified by Sam Raiss at his rooming house and he confirmed she had lived there from October 1 to October 18.

October 22, 1925. Omaha Daily. I was thrown off Edna Oliver’s trail. If anyone in her family has more information, I would like to know the rest of the story. In the end, I was cast down for the multitude of hardships everyone in the Oliver and Christofferson families had been dealt.

Meanwhile Sheriff Endres detailed Deputy Sheriffs Phillips and McBride were tasked with patrolling the river banks and dragging the water at spots where body parts might be lodged. Curiously the department had been furnished a motor boat by the Metropolitan Utilities District as they began a deeper search for the “Head of River Girl.” Fishermen and hunters along the Missouri were drawn into the search and asked to keep careful watch. It was hoped that The River Girl’s head would appear with the rising of the river.

Death of an Unknown Man

Just when things couldn’t get any more tangled, two hunters found a man hanging from a tree in a clump of willows on the Nebraska banks of the Missouri river on Sunday, October 25, 1925. East Omahans E. W. Gonnoll and C. Bushnell happened upon the apparent suicide—a Caucasian male, about 30 years of age, 140 pounds, dressed in a blue suit, army shirt, cap and gaberdine coat. In his pockets were found an Elgin watch, $3.61 in cash, a pocketknife with the figure of a naval officer on the handle and word “Shipman” inscribed, among other things. Also a shaving brush and “a pint bottle with a few drops of whisky still in it” were found on site. The body was said to have” hung there probably a week or maybe two weeks,” estimated Harvey Sautter, special investigator for Coroner Steinwender of Washington County. He thought it was possible this suicide might be related to The River Girl death. He was in the process of examining baggage left uncalled for at local hotels in an effort to establish the identity. Deputy Sheriff Dan Phillips shared, “It is easily conceivable that the man who killed and cut up the body of the girl might have wandered down the bank, perhaps realizing his awful crime and finally, in remorse and horror, might have himself.” Later news suspicioned the man to be from Philadelphia, because of a trademark in his hat. The coat also bore a particular label. The laundry mark, “H” in indelible ink appeared on his shirt collar. “His clothing was of exceptionally good material.” Local mortician John A. Gentleman telegraphed Philadelphia in an attempt to find his identity. Thought to have killed himself, probably after a prolonged drinking spell. Ultimately it was regarded as a coincidence that the bodies of the two dead, the murdered woman and the male who completed suicide were found in the same month, on the same bank of the river, at no great distance from each other.

More Missing Women

Deputy Sheriff Dan Phillips floated a vague tip a handful of times in different tabloids about a missing Omaha woman thought to be The River Girl. He never identified her by name, which was wise considering all of the unaccounted. By November he said the missing Omaha girl reports could not be substantiated and left it at that. During this time Mrs. Edith Heal, mother of a missing Canadian girl came forward with a $500 reward for solution of her daughter’s mysterious January 13th disappearance. Daughter Florence Heal was 20 years old, dark brown bobbed hair, dark brown eyes. Gone from Sarnia, Ontario without a trace.

Young Florence Heal. November 3, 1925. Omaha Daily News.

Mr. and Mrs. C. N. England of Nebraska City suggested that The River Girl might be their daughter, Mrs. Cuba England Ames (sometimes Amos), whom they had not heard from for weeks. Cuba England married Henry Ames in Omaha in the Spring of 1925. The bride’s parents were concerned because they never met Mr. Ames and obviously were not invited to the nuptials. Later the newlyweds moved to Hastings where Henry Ames conducted a photo studio. The England couple received a later in September from their daughter letting them know she was moving to Hastings, (news to the parents) and shortly after the mother sent a special delivery letter. A man received the letter but not reply was ever sent. Cuba England Ames’ descriptors tallied with The River Girl. They asked the police to investigate.

By November 15 the Omaha Daily News delivered a messy story. They described Mrs. Cuba Margaret England Amos as alive and living in Omaha. She had separated from her husband Henry E. Amos (earlier called Henry Ames) and was rooming at 623 North 20th Street, until Friday, “when she feared she would be traced there and left.” The girl said she opposed returning to her mother, who they called Mrs. C. N. England in Nebraska City “because she was chased away when she was fifteen years old.” The World-Herald followed up with their tell-all of the young bride, only 18 years of age. They reported she was now rooming at 1717 Chicago Street and had simply neglected to write her mother. When Cuba read of her mother’s fears, she apparently wrote home. But the “letter was unsigned and in unfamiliar handwriting” so Mrs. England did not believe it was her daughter. Henry Amos had been unable to support her so the couple was living apart. Additional the couple had a baby “that is being cared for by a friend.”

The runaway bride was linked to a rooming house at 623 North 20th Street. This the general area, very near the old Jefferson Square. Looking north on 20th Street from Douglas Street. The oid Omaha Club is on the left. On the right is a mix of houses and apartments. Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). The Durham Museum. 1926.

Like a young Helena Bonham Carter, 18 year old Mrs. Cuba Margaret England Amos was alive. November 15, 1925 Omaha World-Herald.

The drama continued to play out when Mr. and Mrs. C. N. England, their son and daughter came to get Cuba. They visited her rented rooms at 1717 Chicago Street and the home where she was keeping her 5 month old, Mary “but could not find her. They said they would return with the child if the daughter chose to remain in Omaha.” Another article reported her as being “pretty destitute.” I am not sure what became of Cuba Margaret England, but I did find the previous 1920 US Census, which showed her to be the eighth child (living in the home) of Charlie and Jennie England in Nebraska City. There were more siblings after her. Again a very sad story of a young woman enveloped in Omaha for her own reasons.

Another Discovery and Another Grave Opening

It was an odd twist of fate that undertaker Harry E. Swanson should find The River Girl’s arm at river’s edge when hunting in a rowboat. It was November 11th and Swanson was said to be near Florence. Swanson described the arm was white and well preserved, and he would know. “It was caught in the weeds near the shore.” The undertaker put the dismembered arm on the shore and reported his find to Deputy Sheriff Dan Phillips. It was announced the additional body part would be interred shortly.

Sheriff Mehrens and County Attorney O’Hanlon of Blair were at the gravesite for the interment on November 13th. They said they had “no further clews in the probe, but considered a deep scar on the thumb of the arm as the best clew yet.” The River Girl’s arm was laid to rest with her frequently disturbed remains.

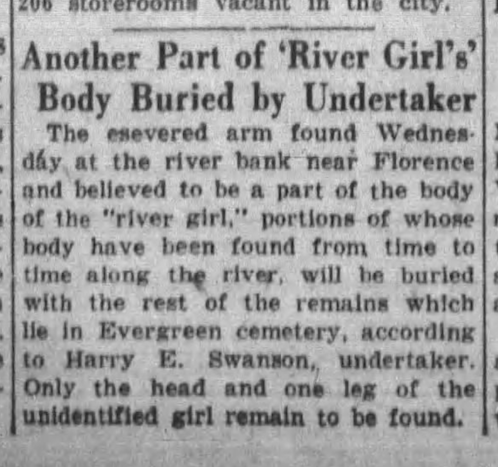

November 12, 1925. Omaha Evening Bee.

Blanche Stewart, Missing Girl

Blanche Stewart, 18 years of age, was reported as the possible River Girl by her mother, Mrs. J. W. Stewart of Verdon, Nebraska. Blanche had disappeared September 17, 1925. The parents had recently learned that their daughter cut her thumb when slicing meat while working for the neighbor, which made them think of The River Girl’s clue. The mother stated that her daughter had been engaged to a Fort Crook soldier, Frank Phillips, now on the rifle range at Plattsmouth. Deputy Sheriff Phillips was planning to pay him a visit. They stated they would return to open the grave again if they didn’t get the answers they needed.

1925 Nov 24 Omaha Evening Bee. “Mr. and Mrs. J. W. Stewart of Verdon, Ne and their daughter, Blanche, shown at the top. The Stewarts are in Omaha in an effort to determine whether their daughter, last heard from in Omaha August 10, may be the mystery girl, parts of whose body were found along the banks of the Missouri river both on the Neb and Iowa sides.”

Later the mother wrote a letter to Deputy Sheriff saying “the descriptions do not tally but that she believes her daughter is being held in Omaha against her will or that she is working in a restaurant.” In a follow up article, Mrs. Stewart said she had found a letter written by daughter Blanche, while visiting in Norfolk. Blanche was “still alive and working in Omaha.”

A Limb is Identified

Another year had turned over without much hope of ever identifying The River Girl. Surprisingly on March 14, 1926 the river presented the last limb of the unnamed girl. Fisherman Joe Polson discovered the left leg about four miles north of Peru, Nebraska floating in an eddy the side of the channel. (Peru is many miles south of Omaha, about an hour if one was driving straight there.) Because it was found just within the boundaries of Nemaha county, Sheriff Charles H. Davis and Deputy Oscar Flag went to Peru and “took charge of the leg.” Sheriff Endres said Dan Phillips was leader in the investigation and would be there shortly. The leg was positively identified by Deputy Sheriff Dan Phillips and Sheriff Morris Mehren as part of The River Girl’s body. Phillips said he was positive the leg belonged to the body “from the manner in which it has been sawed away and by the short, stubby toes. The foot had a high arch and instep, exactly like the right leg.” The leg was brought to Omaha and placed in the Hulse & Riepen morgue. The fourth interment was March 16th.

March 16, 1926. Omaha Daily News.

The Aftermath or My Search Right into the Corner

Then there was nothing. Nothing ever again about The River Girl except to say that William N. Coffey, a “Wisconsin bigamist wife slayer,” who confessed to dismembering his second wife’s body, was the only person (I could find) who had even been publicly suspicioned of being involved in The River Girl case. Around the very same time period, Coffey or “The Rubber Stamp Murderer,” as he was called by the newspapers, was reported to have severed his wife’s body parts and wrapped them separately in newspapers. He admitted to throwing the remains in the river and then later he said he buried each body part separately in the woods. For their part, the Wisconsin authorities did not believe Coffey had any connection with the Omaha River Girl. When questioned about the Omaha mystery, Coffey asserted he was nowhere near Omaha at the time of the local murder and had never even heard of the case.

They never found The River Girl’s head. They never opened the grave again, although it was moved–this I would find out much later.

Miss Cassette Detective Agency Theory

For myself there was still so much I would never understand. Were there clues on some shelf of the Omaha Police Department? How about all of these tipsters that Sheriff Deputy Dan Phillips was contacted by? What led the police to believe The River Girl was killed in an Omaha house? “There is a man or men, fiendishly insane roaming freely, perhaps the streets that every Omahan trods.” Was the Saw Killer of the Omaha Underworld? I don’t think so. Wouldn’t we have heard of this type of killing again in our town? Why couldn’t the murderer have been a farmer up in the Fort Calhoun area or a farmer’s son who picked up a young woman traveling through Omaha or just off the train in Omaha? One person. It would seem to me that his deadly deeds could have been done in a barn or out building without much attention. He could have wrapped her and transported her easily from a rural area to this cliff. This person would also know the area well. I believe her head was buried or hidden as to never be found. I think The River Girl was an out of town, young, blonde come to the big city to work and begin a life. Her family never knew what became of her and maybe this is a good thing.

I would continue to look into any lead I could think of. Sheriff Deputy Dan Phillips who certainly gave so much time and energy to The River Girl case, never spoke publicly in the media about her again. He died at the young age of 55 in the summer of 1938. His obituary read: “Died of a heart attack Tuesday after collapsing while eating breakfast.

He once gained fame as leader of Sheriff Mike Endres’ ‘raiders’ in Douglas county during the prohibition era, and also had been a member formerly of the Omaha police morals squad and before that a railroad detective. For the past few years he had operated the Phillips Produce company in Omaha. He had been ill about six weeks.

Surviving him are his widow, Mary; three sons, Irwin of Rock Island, Illinois, Ray of Omaha and Thomas of Beacon, Iowa; three sisters, Mrs. F. C. Sobeck of Green Bay, Wisconsin, and Mrs. G. R. Reay and Miss Marie Phillips of LaCrosse, Wisconsin.”

The Hastings Daily Tribune. August 30, 1938.

My Gravesite Visit

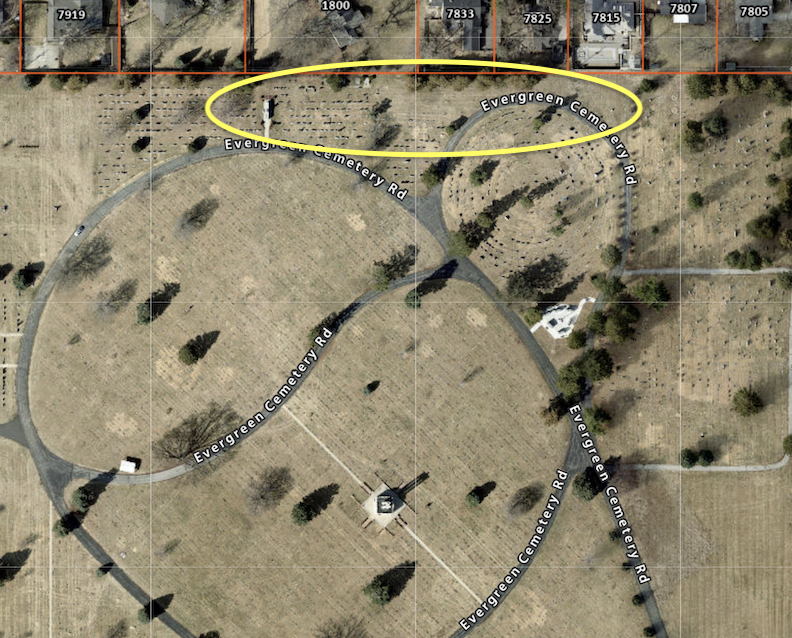

I could not believe my luck but after reviewing the Evergreen Cemetery and a burial site, I knew The River Girl was in Section F; Row 3; Grave 8.

After all this time, I mustered the will to go walk the cemetery rows and try to find The River Girl. Of course it was raining and ever so windy.

I worked the whole Section F area. My umbrella blew inside out a number of times. Was I being filmed? Finding a Row 3 became complicated by the fact that there was a north and a south with paths in between. It became psychotic. There was no River Girl.

I called the Evergreen office the next day and spoke with Nick. He offered to help me find the grave. It was through this meeting that I learned Section F Singles is very different than Section F. Nick was very kind.

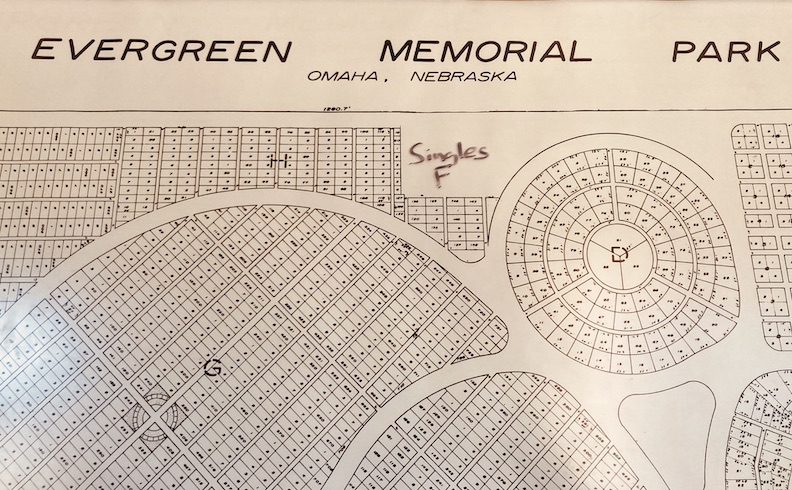

A portion of a very cool map of graves in the Evergreen offices.

Nick brought me to the correct area, up north and then walked the plots with his directory until he found what he thought was The River Girl. He was diligent. Sadly there was no marker, no grave designated “with the inscription ‘The River Girl,’” as it was back in 1925.

Interestingly Nick noted that the whole of Section F Singles had been moved within the cemetery, although he wasn’t sure when. He added that it had not happened in the time that he had been employed there.

Section F Singles Row 3; Grave 8. This is where The River Girl rests now. Three rows south of these two trees. Directly to the left of her grave is the flat headstone of Duane Dennis Field. To The River Girl’s right (or east) if Baby Richard Widman. It is very hard to find, honestly and without the inscription of The River Girl or even a blank, flat marker, I felt a heaviness. Had her marker been damaged with age or with disinterments or even with the last move to the new area?

Using the historic DOGIS aerials, I was able to see when Section F Singles was plotted. I would guess the cemetery staff moved the Section F Singles in the very late 80s to the early 1990s. Aerial from the DOGIS site; the yellow oval is where The River Girl is buried.

The Police Files

I called the Omaha Police Department and spoke with Officer Chris Gordon, who was very nice. I explained what I was working on and that I was interested to know if they had any 1925 or later case files on The River Girl. I really wondered if they ever had a suspect or suspects that they’d received tips on. I also needed to know why they thought The River Girl was killed in an Omaha home. Within a day I heard back from Officer Gordon– that they were able to have the OPD records supervisor look through all of their historical records and they found cases from 1922, but unfortunately there was a gap between 1923 and 1933. No case files. “Looks like your case of interest falls in this gap of lost documents.” Dismayed and perplexed. Did these missing case files point to an even bigger mystery than The River Girl?

Much thanks for Officer Chris Gordon, Omaha Police Department, Nick and staff at Evergreen Cemetery.

For The River Girl and all the mystery women who came to Omaha for their own reasons.

I welcome your feedback and comments on The River Girl case and 1925 Omaha. Please share your additional clues to the story in the “Comments,” as we know more together. I am actively looking for any family connections with the found missing girls. Everyone would love to read what you have to say and it makes the sharing of Omaha history more fun. You can use an anonymous smokescreen name if need be. We want to hear from you.

You can keep up with my latest investigations by joining my email group. Click on “Contact” then look for “Sign me up for the Newsletter!” Enter your email address. You will get sent email updates every time I have written a new article. Also feel free to join My Omaha Obsession on Facebook. Thank you, Omaha friends. Miss Cassette

© Miss Cassette and myomahaobsession, 2024. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Miss Cassette and myomahaobsession with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

If you are looking for more architectural and Omaha history sleuthing fun, ask your local or bigbox bookseller for my book: My Omaha Obsession: Searching for the City. Also available everywhere online. Thank you.

Wow. Deeply sad. Dark and depraved. Gruesome and cinematic.

I do think it’s hard to imagine what Omaha was like during that period from only photos and news clippings. Putting it all together in such a thoughtful narrative brings it to life. So few traces of early Omaha’s physical history have survived to remind us as we move about daily life in the city. Our sense of place is only a feeling, or feelings with memory, and somewhat intangible.

Had the murder taken place in more recent times, it might have been solved today through DNA.

Was there evidence the “river girl”had been sexually assaulted? Was that even a consideration in those days? You really get an alarming impression women had a tough time navigating the world then.

As I continued to read, I was thinking of season 4 of Fargo. Oddly, despite that story being set in 1950, the violence, the dark mood, the set pieces, and the dress of the men and women seemed much earlier to me, more like the late 20s of this sinister tale.

And where is the head today? Did the murderer actually take the time and effort to bury the head? especially after crudely hacking the body into pieces and clumsily attempting to toss the pieces into the Missouri river? Did the head travel down the Missouri River all the way to the sea? Did it not snag on brush or debris like an arm or limb might?

Somewhere lies a head, and somewhere lies a murderer (or murderers) who may have been alive as late as 1990–2000.

Hello Howard, I really appreciate your thoughts–as always. I found no evidence The River Girl being sexually assaulted. I wondered if they would have mentioned it but the more I searched it seemed they did mention in news articles of the time when someone was sexually assaulted. Like you, I had thought about the killer and the manner in which he left The River Girl. this is going to be even grosser than what I wrote previously–Wouldn’t a head have floated in the river? Why would the killer risk that? But then again, he was not the sharpest… maybe young. Why risk throwing her head in and having it float? Wouldn’t people have seen it from the river’s edge? But then I wondered if he had shot her, maybe parts of her head were destroyed. Easier to just throw away in the trash? If one considers that he dismembered her to easily transport her, to hide her and not just for sick folly, then you’ve got to wonder if he was moving her out of an area with a lot of people and wanting to hide detection. Which might lead back to the detective’s theory of the killing take place in Omaha. Ultimately the head was the only means of identification, if it had a good deal of integrity. Could it have been a souvenir? I think it could have been destroyed due to the manner of killing.

I wonder if the killer was in the Mafia? Sioux City was supposedly a place the mafia would go to lay low. I believe I read Al Capone would hide out in Sioux City when he needed to get out of Chicago.

So, what if the saw killer was a short-tempered psychopathic mafia thug traveling cross-country with the river girl? What if river girl was a prostitute he picked up in Sioux City or Omaha? You note the “dirty side of Omaha”had fourteen houses of prostitution, four bootleg joints, and four gambling houses.

Maybe the two violently argue and he goes psycho and, excuse me for being graphic, blows her head off in a field somewhere between Sioux City and Omaha.

Omaha wasn’t exactly a metropolis in the 1920s. Certainly not compared to today. In fact as late as the 1950s, 72nd street and Ak-Sar-Ben was still considered rural countryside.

My mother had an art school friend who drove a cab and was murdered near Ak-Sar-Ben in the late 40s or early 50s. I can’t recall the details, but it was front page news back then because the murder was so violent and involved a manhunt.

True-crime stories like these are reminders that a very dark, rough underbelly must have existed in Omaha during the first half of the twentieth century.

I wonder if Edna remarried?

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVGD-TZHT

Hi Tim, Somehow I am not able to open this link. Maybe one needs to be a member. Thanks for sending it, regardless.

Some additional hits

Perhaps we should raise money for a grave marker….

Please keep investigating “Crime Files”! It was very interesting!

Thank you so much, Dawn. It was quite an experience. I do have another one halfway done. Thanks for the encouragement.

I am trying to read all the stories in your blog in chronological order. I am currently up to late 2018. The stories are enjoyable and are teaching me a lot about Omaha. I believe we are a similar age. You have mentioned a few people you know from Omaha’s music scene from the 80s and 90s that I also know. Mostly from going to Dirt Cheap, Homer’s, Drastic Plastic, record shows and concerts. Thanks for the stories. Luckily, I am retired recently and have time to read the long stories. 🙂

i think i know who the river girl is