I found the letter placed on my desk. The envelope had been tidily cut open with a paper knife, its contents, a single sheet, still crisply folded inside. I presumed this was Mr. Cross’s passive way of letting it be known that he’d like to resume his duties in the detective office. We’ll see about that, I smiled, to his newly turned back. He does bring a certain amount of life and color, despite his insufferable sniffing and pouting about.

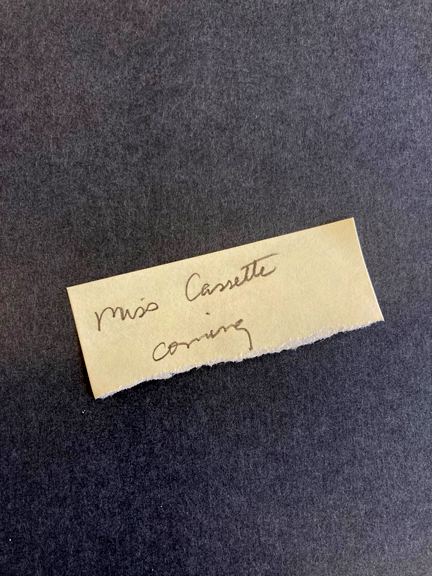

Dear Miss Cassette,

My book club is reading your book, and although I thought I had read all of it before, I am newly struck by your stories of the Woolworth family and their houses and can’t figure out why I didn’t tell you about an amazing thing we have here about them–though it’s possible it came to light after you did your original research…

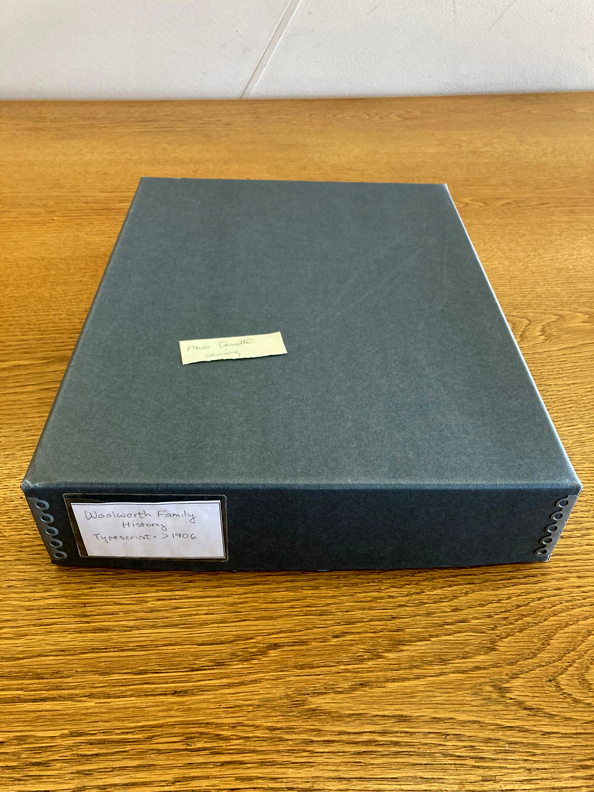

A favorite librarian around these parts, Martha Grenzeback of the W. Dale Clark Library, had written me and indeed had unearthed my idea of the gold-covered wooden chest from some remote backroom shelf. Unfortunately or fortunately, the library would discover this scrumptious two-volume history of the Woolworth family, only after I had turned in my manuscript to the publisher. The Woolworth investigation that I completed for my book, “The Clue to Bircheknolle,” was possibly one of my favorite cases, in that the Woolworths and the homes they built and their later uses, just enchanted as I tumbled down the rabbit hole. In my estimation, the fact that Martha had found new Woolworth clues was surely a treasure trove of the highest order. Even on the grimmest of winter days, I must have skipped down to the W. Dale Clark Library for I knew there glowed a brilliant bouquet of flowers awaiting me.

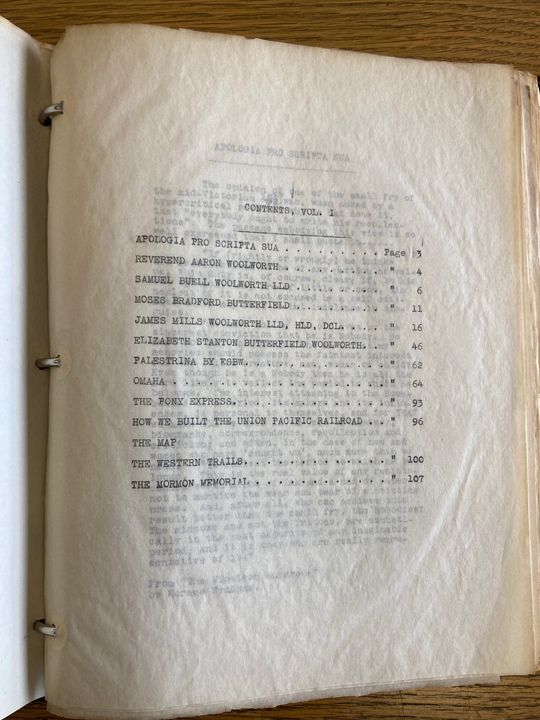

James Woolworth’s daughter, Meliora Woolworth Fairfield, wrote the found typescripts, possibly for a family history book, sometime after 1906. The thin, old time, typewriter pages were filled with intimate, compulsive, detailed descriptions of family and their homes included lovingly hand-drawn floor plans and rare, family photographs of the structures’ interiors and exteriors—they are an architectural Nancy Drew-ers transport of delight. To read Meliora’s depictions of life at home on the St. Mary’s Avenue hill lifted me in the wind like a small, downy under-feather and whipped me into little circles—to read the real life voice that I only imagined in my investigation! She had a keen eye, thoughtful, opinionated but composed and was painstakingly honest in a way that set me atwitter—as if I was poring over her private diary. I can’t imagine the context of a society woman divulging those perceptions, dishing on both family and famous Omahans, unless it was for future relations….but even then, she was famously the first Queen of Quivera at the original Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation Ball. She was a true writer. It seemed impossible that I could be allowed this deeper view so long after the research. Miss Meliora, Woolworth’s youngest daughter, was obsessive—just like us.

The best archival box awaiting me at the W. Dale Clark Library with a smile-producing note.

I had talked with my publisher years ago about including supplemental photographs on this website as complementary chapters to various investigations in the book, as I wasn’t allowed nearly enough images due to cost. On that note, here I am suggesting my book—My Omaha Obsession: Searching for the City and nudging that you specifically knuckle down to “The Clue to Bircheknolle.” The history of the family, the houses and what transpired after is laid out there and is not the purpose of today’s exploration. We will be rummaging through Meliora’s dossier and you certainly don’t need to have read my previous investigation to find joy in today’s collection.

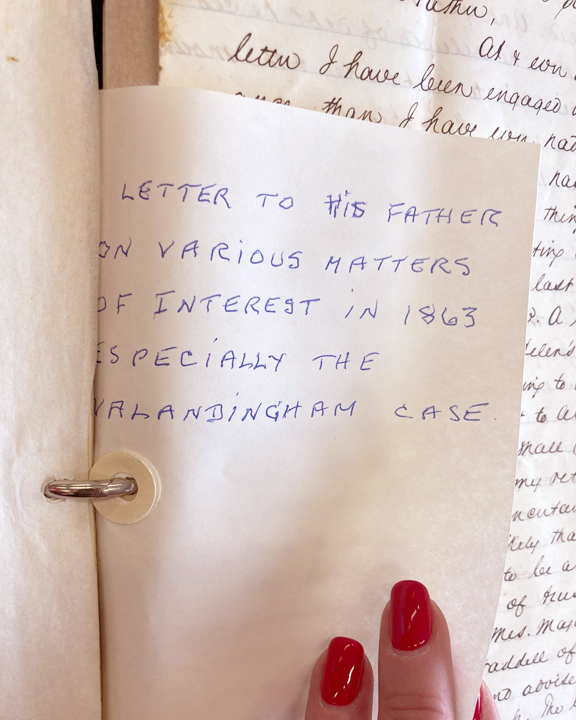

The table of contents and a secret note, pages later, announcing a handwritten letter by Judge Woolworth himself. Ballpoint pen? Classic white hole reinforcements? A thicker, more modern paper stock? Seemed evidence of a librarian of long ago, but certainly after 1906.

The voluminous onionskin papers were translucent in my hands. For as thin as it was, onionskin proved to be exceptionally crackly and loud. I was not the Mystery of Fog I aspire to as I turned each resounding, glorious page and I feared every bibliophile around me was casting quieting spells in my direction. There was one older fellow, a regular, scanning and turning his newspaper pages while crunching chips, who made me feel a bit better. Truthfully I wished I could steal away in private and hug and smell that perfectly catalogued, slate archival box with the metal edging. I still dream of it. Divine. To peer at Judge Woolworth’s hand-penned letter and take in the love with which a daughter toiled to collect and arrange her family’s legacy… My sainted aunt! I couldn’t believe my luck. I found many original photographs of 2211 and 2219, the family’s homes on St. Mary’s Avenue. Well….let me show you what I found. But first a bit of back story, if you are wondering what all of the fuss is about.

A Quick Woolworth Review

I won’t respade too deeply here. James Mills Woolworth was born in Onondaga Valley, New York in 1829. Omaha would come to know Woolworth as its first attorney, “a judge,” a politician, a history writer, a wealthy venture capitalist, and a real estate mogul. He was considered a Pioneer of Early Omaha, having moved to town in 1856. James and Helen Marie Beggs were married previous to moving here; son Charles was born in 1855, daughter Jeanie born in 1859. There were other mystery children that I discovered and purled on and on about in the book. Because mysterious, disappearing-from-history-book-people, particularly children, just as mysterious, disappearing-from-view houses, are what I adore.

The James Woolworth family lived in downtown Omaha, as most early Caucasian settlers did. I had tracked a number of possible addresses in my book. By 1871 James married second wife Elizabeth Stanton Butterfield (first wife disappeared to much conjecture in my book) and the couple has two children: Meliora Clarkson Woolworth born in 1873 (author of the Woolworth family collection that I will be borrowing excerpts from) and Robert Harper Clarkson Woolworth, born in 1874. Little Robert died in 1879. The family builds the handsome residence at 2211 St. Mary’s Avenue in 1880, my fixation–naming it Cortlandt, which wouldn’t be its only function or name in the troubling years to follow. In 1900 James Woolworth would have a delicious Tudor style home at 2219 St. Mary’s constructed on the western portion of his large property for daughter, Meliora and her new husband, Edmund Minor Fairfield. My main driving obsession was figuring out how the two Woolworth family houses at 2211 and 2219 St. Mary’s came to be and why they would transition into what they became. The investigation only got stranger from there but for our purposes today, I believe we are sufficiently up to speed. Oh yes, except that I forgot to mention that the 1950’s Rorick Apartments turned City View Apartments at 604 South 22nd Street now stand where the mansions once were.

Now we are ready.

The original photograph that inspired my investigation of 2211 St. Mary’s—the glorious home and grounds of the James Mills Woolworth family. Off to the right is daughter Meliora Woolworth’s home.

City View Apartments 604 South 22nd Street seen from the east side on 22nd Street. Photo I took in 2017 on a reconnaissance mission.

A Judge? Meliora Spills the Tea

First things first. I like to give credit where it is due. Dave Sommers, Esq. alerted me a while back that The Omaha Bar Association book club read My Omaha Obsession: Searching for the City. In reading, they found an error, which Dave kindly brought to my attention. I had quoted from an OWH clipping found at the library’s reference desk, where James Woolworth purportedly was elected Chief Justice of the Nebraska Supreme Court in 1873. Dave’s correction was that George Lake won that election. So I begin quarrying again and while it is true Woolworth was the Democratic party’s candidate for the position, he ultimately was not elected as Chief Justice of the Nebraska Supreme Court in 1873. Thank you Dave and thank you OBA book club. (Hello to Judge Coe!) I have sent word to my publisher, but it might be too late and I will forever be peddling more misinformation.

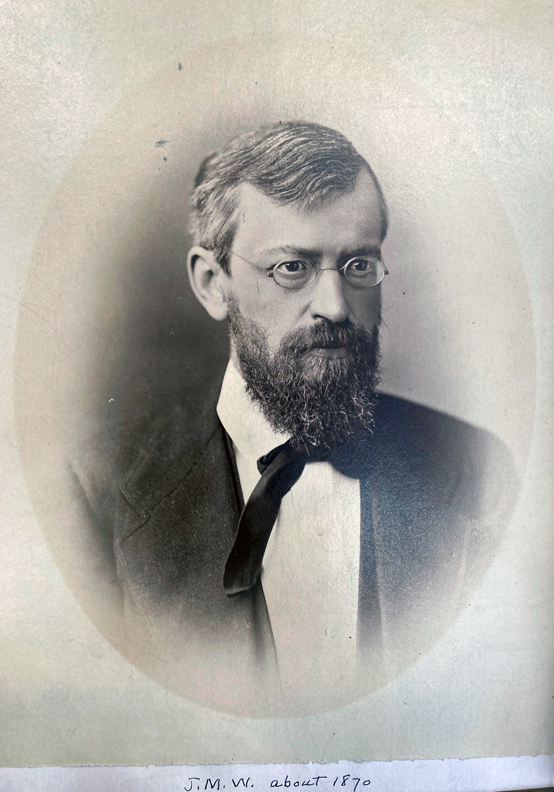

1870 James Mills Woolworth photo. Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

I thought one could become a judge through another path, other than winning an election, but as it turned out in this case, the highly esteemed Judge Woolworth was not even a judge. I learned from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s typescript: “The young lawyer was City Attorney in 1857, unsuccessful Democratic candidate for Chief Justice of the State Supreme Court in 1873 and was commonly called ‘Judge Woolworth’ thereafter, though he never had the right to the title, and disliked it, preferring to be called Chancellor.” So it would appear that the name “Judge” was merely a nickname like “Boss” or “Chief” and one that not only my publisher would need notification of, much of Omaha history might need to be amended.

MWF thoughts on her father’s early career:

“There was little business in Omaha at first but land speculation was rife and was the cause of much litigation. My father’s practice grew to such an extent that in 1858 a young lawyer who came to Omaha from New York intending to practice his profession soon departed saying there was no room for him, for ‘Woolworth and Poppleton have an unbreakable hold on the law.’ Later this young man, Chester A. Arthur, became Vice-President of the United States and President after the assassination of President Garfield.”

MWF’s thoughts on the mysterious death of father’s first wife, Helen Marie Beggs Woolworth and the early years in Omaha:

“The change from the comfortable familiar old home, full of friends and relations to the new, raw settlement, with its just storms, great heat in the summer and severe cold in winter, little service and that untrained, ubiquitous Indians squatting about the kitchen door demanding food, who, though pacified, were always an unpleasant and uncertain element, frequent child bearing, and very poor medical care, broke the wife’s health and she died in a few years. She left two young children, Charlie and Jeanie, to whom their father was devoted nurse and companion as well as break winner through their childhood, until his second marriage in 1871 to Elizabeth Butterfield, Principal of Brownell Hall, Bishop Clarkson’s church school for girls.”

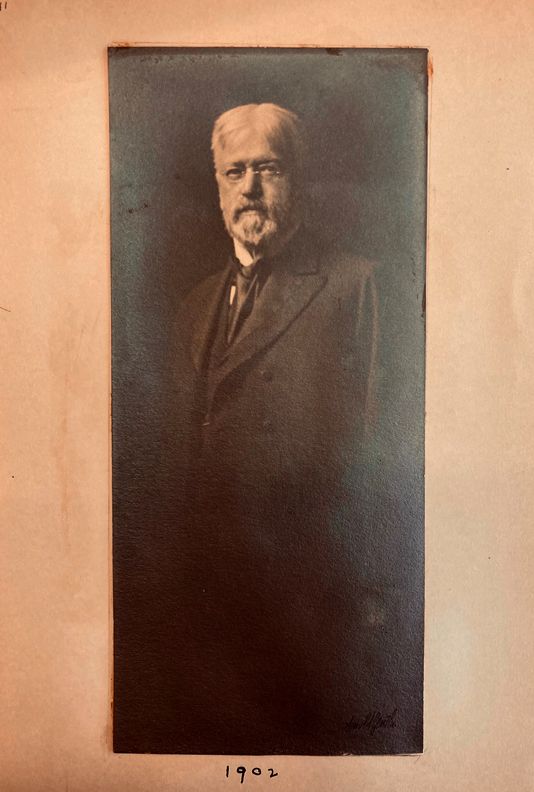

1902 photograph of James Mills Woolworth. Image borrowed from the archive of Meliora Woolworth Fairfield. W. Dale Clark Library.

MWF on her father:

“He was a sensitive affectionate impulsive and emotional man, easily depressed and easily enthused. His temper was hasty and irritable, too quick to be always just, but patient and long suffering with his children. His interest in their affairs was never failing and no demand upon his time and sympathy could be too great, and his letters are filled with his affection for them, his anticipations of their success and his unending concern for their health and happiness, and he could deny them nothing that his purse could supply (…) His additions to his library and his house and grounds were never ending, so that although he was supposed to have amassed wealth as other less generous men did, he was often in debt until a big fee came in, which was spent clearing up his notes and on new possessions, a journey or on his family.”

MWF on her father’s later years:

“Except for buying beautiful clothes he had been careless of his appearance and had never taken exercise, but in his later years he set up a masseur who came several nights a week and on Sunday mornings gave him a two hour session from which he emerged rosy and immaculate, his nails manicured and his white hair shining. He was proud of his vigorous health and youthful looks and used to say to me when we were traveling, ‘See those people? They are saying, ‘Who is that old girl with that young fellow?’ At seventy-four he was stricken with diabetes and as there was no insulin in those days, spent a painful three years in physical and mental decline and died in June 1906 and was buried from his dear Cathedral with the full choral service he loved. “

The Posh End of Town

We often complain of potholes here in Omaha—cheap aggregates in the concrete is what we’ve heard. We are a frugal, long suffering lot, aren’t we? But we pay in the end for our short cuts and short shortsightedness. ‘Tis our sad, little, simple, circular way. Meliora included a quote from the Omaha Herald, as it was called in 1868, that she obviously found apropos. This was her introduction to a very colorful reminiscence on the chuck-holed streets of downtown Omaha.

“’Near 12th and Douglas Streets yesterday there stood in the mudhole a white barrel upon which was painted in large letters, ‘No Bottom. Trains leave daily for China and intermediate point.’

As a child I had rubber boots and so had my mother for use in neighborhood visits. If we went any distance we drove, and not infrequently we could not do that. Rubbers were sucked off in crossing streets, and after the streets were paved the foundations of the work was so poorly done that I have seen a horse break through the asphalt and disappear, where the soil had washed away underneath. Sometimes the horse which fell into mud holes could be drawn out with ropes and a team, sometimes nothing could be done and they were abandoned. Long before the streets were paved the first streetcar appeared-an old stage coach bought for $700.00 and put on flanged wheels, with the driver perched up on the original high seat.”

“Omaha in 1875, from 14th and Farnam.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

“As most buildings were of wood brought from down river on the steam boats—there being no stone or timber suitable for buildings on the Missouri,–fire was an ever present menace. The hook and ladder company had no bell, and that on the Lutheran Church next door was rung for fires.”

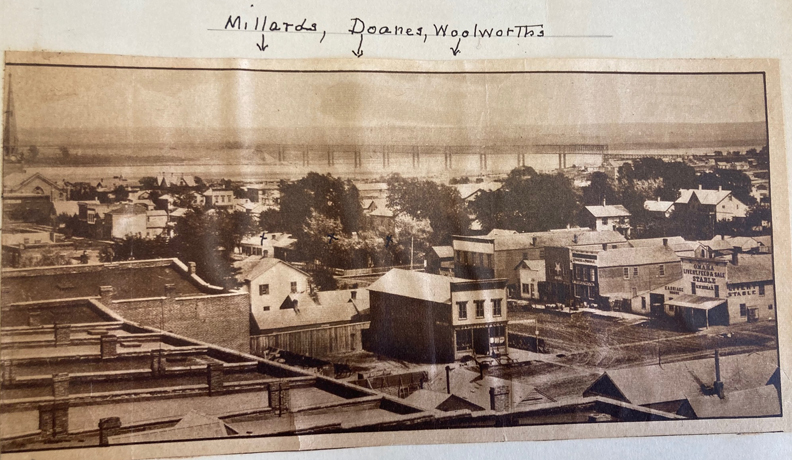

Where the Smart Set resides. The homes of the Millard, Doane and Woolworth families. Love the hand drawn labeling with arrows. Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

The Early Home

In my book I had traced the early Woolworth home to 1218 Howard, very near the heart of what is now the Old Market, at about the Omaha Healing Arts Center (OM). I would read of Rasmus Petersen, former president of the Gate City Malt Company of South Omaha, who along with his wife, turned the “old Woolworth home at Twelfth and Howard” into a large, profitable boarding house. I was not able to gather much detail on the residence but knew it must have been of good size. To find Meliora’s photo of 1218 Howard and description filed in her dossier was so satisfying to me.

“First Woolworth house at 12’ + Howard Sts.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

“The house where I was born was built by my father in the 60’s—a cream painted frame house with dark green trim a and blinds. It stood in the middle of a quarter block, and his two room office was in the upper corner of the lot, with its own gate to the street. The ground was flat and its chief beauty was the row of tall locust trees that surrounded it, so fragrant when in bloom.” She goes on to describe the high style interior “French, of the Third Empire,” the Library with its black Brussels carpet with red roses and green leaves and “the dining room of the ugly walnut that most people had in the 60’s and 70’s.” Gasp.

Elizabeth Stanton Butterfield Woolworth and the New House

I particularly savored Meliora’s perceptions of her dear mother of exceedingly good taste–with examination paid to her interior design, furnishings, the arts, fashion, study of child psychology, Society, her aquiline nose and “extremely fine white skin,” her greatest beauty—noting that “her face became a little weather beaten from the harsh Nebraska climate.” YES, we all know what you mean, Meliora. Mother Elizabeth had progressive beliefs about child rearing, education and the poor. What Meliora had labeled “radical ideas” for the time. Any daughter of any time would understand the words, “She was considered handsome though her figure was short waisted and she stooped, which was doubtless why she was insistent that I be trained to ‘stand up straight.’” Of particular interest was the mother’s life long commitment to Republicanism, “in spite of the equally convinced Democratic principles of my father. I suppose they had argued out their difference of opinion in past years for I never heard any political disagreements between them, though they made fun of each other’s politics at times.” It was exceptional, intimate reading that I could retype into oblivion here today, so I will put the breaks on at this juncture. But it is important information to take in that the home at 2211 St. Mary’s was built after Elizabeth fell into a deep depression subsequent to the death of her four-year-old boy.

“After the death of her own boy she was so shocked and resentful of the lack of all proper care by the old and incompetent physician that she fell into an alarming state of depression that was almost melancholia. She had always been subject to fits of great depression and the condition was so extreme at this time that my father put seriously in hand the building of the new house on St. Mary’s Avenue which had been under discussion for some time, in the hope of distracting her. Her taste and good judgment were evident in its comparative simplicity at a period when house decoration was beginning to emerge from the ugliness of the mid-Victorian bad taste into the over elaborate but better taste of the new Eastlake designs.”

I would behold with anticipation as Mrs. Woolworth took up the distraction of luxury rug buying and all matter of sophisticated interior furnishings. Meliora described her mother was “not as happy during several years as she should have been” after the death of her little boy—what we now know is normal, understandable grieving. Of note, Mother Elizabeth Woolworth never lost her passion for music and that seemed to bring her through her darkest days.

Although I knew young Robert Harper Clarkson Woolworth had died suddenly and the stately home with an imposing nature at 2211 St. Mary’s Avenue had sprung up not long after, I had no idea the new residence and the planning of, was hoped to improve the bereaved mother’s resolve. It seemed the whole corner suggested a poised dignity, a sought after state of being. I will think on that for a long time.

The Cortlandt Lookbook

2211 St. Mary’s Avenue was located just south of what is now referred to as the Park East area. The large southwest corner lot sat facing east on what is now called 22nd Street, originally South Avenue; its northern most border ran along St. Mary’s Avenue. This plat is between what is now the Hillcrest Addition and Cortlandt Place Addition. Omaha Illustrated christened the Woolworth mansion “One of the most handsome residences in Omaha.”

MWF’s writings on the early 2211 St. Mary’s:

“For some time there had been talk of a new house further West, to get away from encroaching business and to give more room for the ever increasing library. (…) An acre and a third was bought ten blocks above us on St. Mary’s Avenue, close to the Clarksons and so far out that there were on a few sparsely settled streets between us and the virgin prairie so that I often watched the prairie fires from our upper windows.”

I will admit to a good deal of ruminating on “Cortlandt,” the residence and grounds named by the Woolworths, in my book. But had I had a chance to see the following photographs, I would possibly still be writing the book for they are shiver producing. Hold yourselves.

“Larsen. 2211 St. Mary’s Avenue from The North. 1881.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

Notice the labeling of “Larsen.” He was someone I did a good deal of obsessing about in the book. We will discuss him in a bit as Meliora lent even more clues. Here was see 2211 St. Mary’s in its first years. Quite a stunning vision. Note that “Cortlandt” is spelled out on the garden lawn. Also one of the early streetcars tries to inch its way up the treacherous St. Mary’s route. I do believe the streetcar driver might be posing with Mr. Larsen?

“The effect of the house is marred by its placing on the steep hill which runs up to it from the street. It is set due East and West instead of straight with the street which turns at 17’ Street to run North West, and this makes the house seem to tip up at the East end. Endeavors to remedy this defect by thick plantings of shrubbery and trees failed, for the fierce cold and North Winds killed most of the vegetation on the North side. The South side of the house is the more attractive, partly for this reason.”

The more I pored over Miss Meliora’s writing, the more I found answers to my questions. It was such a large reward.

“For several of the first years there the name of the place, ‘Cortlandt’ was planted in dwarf red coleus on the North lawn. This looks to us now like a suburban railroad station but it was then rather often seen, and there was a sentiment about it, for both my parents came from Cortlandt County in New York. The wall around most of the place was of pale cream stone and was, I understand, a very fine bit of stone laying. It had a little sharp spiked iron fence on top which was, I believe, much resented by the children who wished to run along the wide wall’s top.”

“Old High School. Old Douglas C’y C’t House. View Toward Northeast, 2211 St. Mary’s Avenue, 1881.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library. Lovely view from the Woolworth porch. To finally see it…

“1882.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library. Love the horses passing through the porte-cochère.

“Its construction was of great beams bolted together and the work was done by day labor and by hand, instead of by contract and with all doors and windows coming ready to use from the mill, as is done now. This was, of course, very expensive and my father told me years later that he had never admitted its cost—nearly 30,000 dollars—a very big sum for those days and for a town like Omaha. All the woodwork inside and out was put together by hand—every edge on the outside was chamfered and this work and its painting, down with a small brush, took much time and was costly. These flat edges, the doors, window frames and shutters were of greenish black and the house was very dark red, the roof of ‘blue’ slate patterned with red and the little iron fence along the ridge which matched that on the stone wall around the place was black picked out with gilt.”

The southern view of the Woolworth mansion. 1898. Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

Detail of my favorite details.

“2211 St. Mary’s Avenue, from the East. 1898.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

Detailed view with carriage house in the rear.

“There were two big cisterns for rainwater as there was no municipal water system at the time the house was built and we had the luxury of soft water, both hot and cold.”

Cortlandt’s Interiors

“Parlor-Library Dining Room Hall from front door. 2211 St. Mary’s Avenue. 1881.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

I stepped through the front door and stopped dead. If you look closely, you will see Miss Cassette hard blinking, floating up the stairs as if levitating in a sepia haze.

“Parlor + Library, 2211. St. Mary’s Avenue. 1885.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

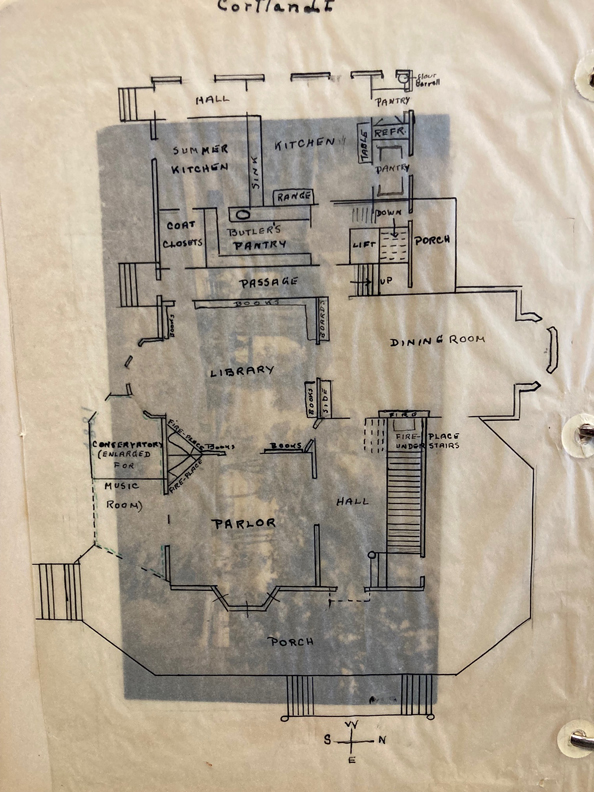

Meliora’s lovingly hand drawn floor plan of Cortlandt’s first floor. Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library. This is an exceptional layout for ease and grace of socializing. I really like how the porch wrapped across with access from the dining room for an after dinner stroll or smoke.

“A glance at the plan of the lower floor of the house shows how carefully it was arrange for arriving guests to that there should be no jostling of those ascending and descending. Carriages arrived at the South door by the library, people went up the back stairs to the dressing rooms and came down the front. My mother made a point of this arrangement and it added much to the looks of a party, as well as to the comfort of the guests.”

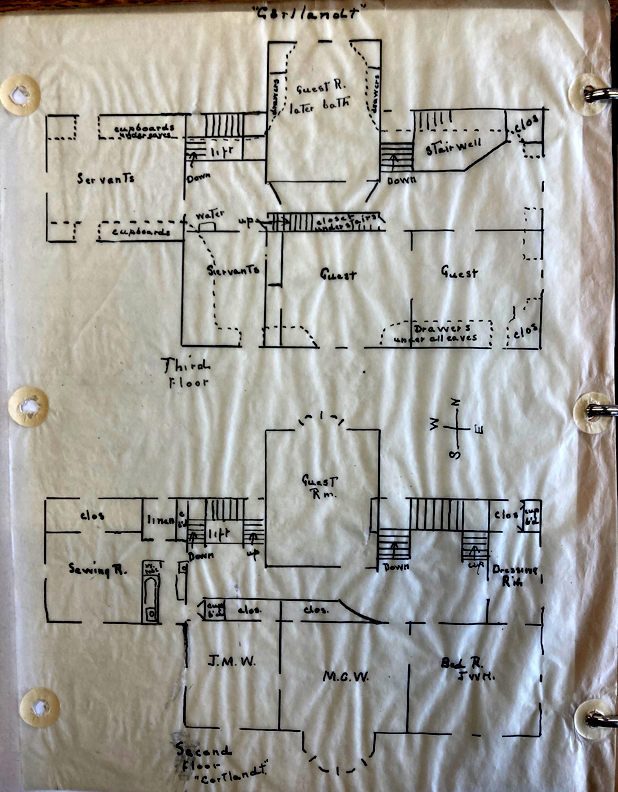

“Second Floor, Third Floor Cortlandt.” Meliora’s very detailed floor plans of Cortlandt’s second and third floors. Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

I was interested to learn that there was a fourth floor, which Miss Meliora did not draw up and trunks were stored there. She also described multiple stairwells from the cellar to the top floors, described as horribly drafty and “unendurable.”

“The wood in the hall was red oak, the parlor of soft white pine which takes a beautiful finish and is, I believe, unobtainable now. The library was white oak, the dining room natural cherry, unstained, with a carved mahogany mantel, that in the parlor white mahogany. The backstairs elevator and hall were oak and all the upstairs halls and rooms were Georgia pine, painted. The one bathroom and the butler’s pantry were pine rather elaborately paneled with walnut.”

Trust me, when I say with delight, there were practically volumes devoted to the descriptions of the Cortlandt woodwork. There are many more pages elaborating about wall coloring and rugs and fringe. It was divine.

“Library. 1898” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library. This, to me, is perhaps my favorite image. Mr. Woolworth’s pride and joy—his book collection. I have always loved a dark, rich stained wood.

“Parlor. 1898.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library. It is interesting to view how the parlor and décor had changed since the earlier photos. Mrs. Woolworth passed away a year before this photo was taken.

2219 St. Mary’s Avenue Lookbook

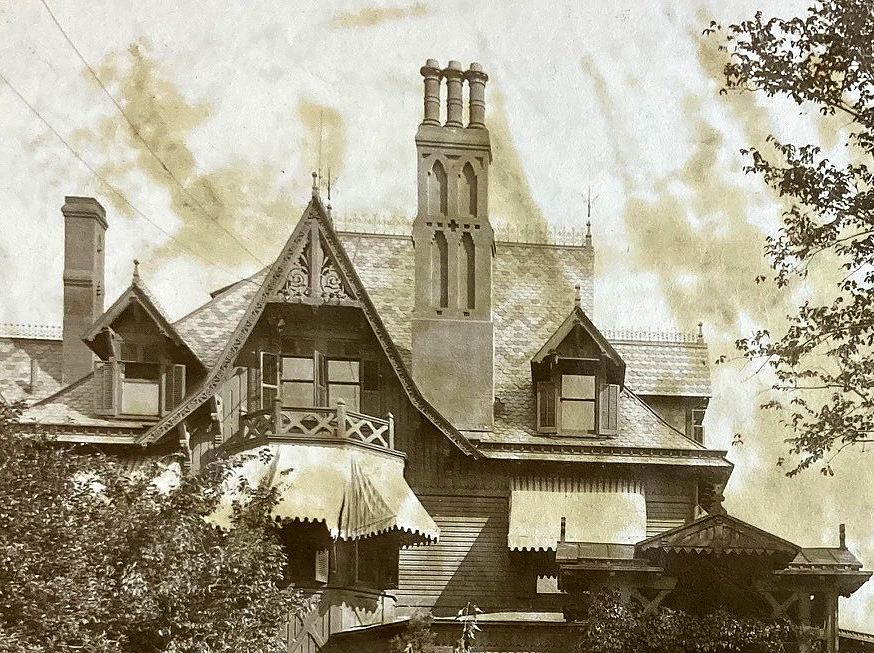

When Miss Meliora was to marry Edmund Fairfield in 1900, Father Woolworth would not hear of the couple’s plan to reside at Omaha’s first apartment house, because he thought it uncivilized. He wanted Meliora close to him and hired on Architect Thomas Kimball to design a home on the northwest corner of the Woolworth estate. After much deliberation about the architectural style of the home (originally proposed was a house of the same characteristics as Mr. Woolworth’s), they settled on “what Mr. Kimball called 13th century domestic Gothic.” This is what Miss Cassette labeled a Fairytale Tudor in the book but with these new photos to drool over, I am simply calling 2219, Devastating. It was wonderful to finally receive this confirmation about the architect and fasten down the Kimball name.

“North side-entrance, 2219 St. Mary’s Avenue. 1902.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library. The rare full timbering had a striking, Tim Burton playfulness. St. Mary’s Avenue provided the entry point to the Fairfield property, but the formal front of house faced east or was it south? Note that by then St. Mary’s had cobblestone.

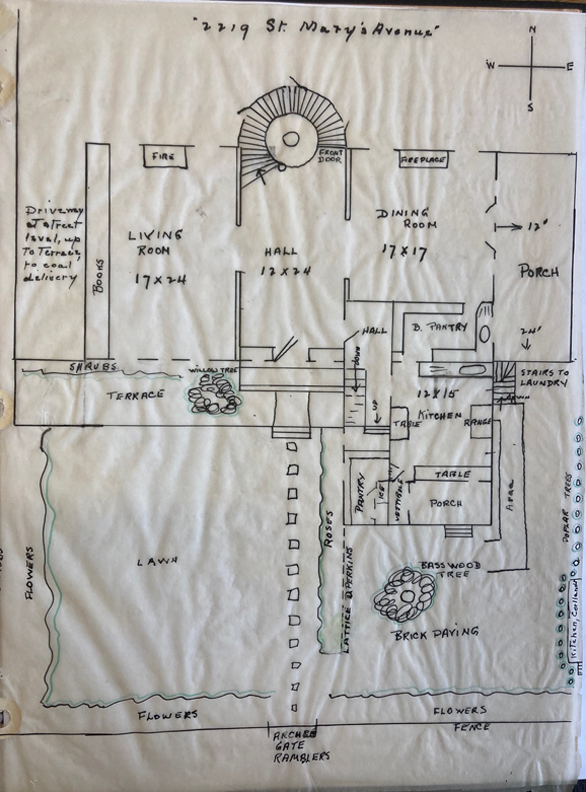

MWF’s explanation of the unusual entry drive to her home:

“The lot was short and I wanted all possible space for the garden—hence placing of the house close to the street on a sharp slope which necessitated the peculiar entrance and, to get the coal into the South side of the house, another bewildering affair, a short drive ending in a high brick wall up to the top of the terrace, with a blind arch in it and a big iron ring in its midst. This was even more puzzling than the entrance and people stood and stared and conjectured—“Was it the entrance to the wine cellar?” Not at all. It was an inspiration of Mr. Kimball’s who planned that the horses should be unhitched from the coal wagon, a rope fastened to them, run back through the ring and fastened to the wagon, so that when the team was led forward the wagon would back into the drive up to the coal chute—a perfectly practical and sensible arrangement but too unusual for a driver to cope with and they continued to back their wagons into the place in spite of explanations.”

Let’s magnify the northern, street level door. I was fascinated by this entrance when I was in research phase for obvious reasons. It was a real puzzler. I just love Meliora’s narration.

“The entrance from the street was planned to protect anyone arriving at the house from the snow and fierce North winds in winter, and was perfectly charming and perfectly bewildering to the uninitiated. One entered through an arch into a large semi-circle paneled to the ceiling with dark oak and saw ahead two broad steps leading to a wide low door with heavy iron hinges and a tiny peephole but no bell. To the right stairs ran up around the outer wall lit by small casement windows of amber bulls-eyes and a pierced oak screen on the inner side. At the top was the front door, but the inexperienced feared to make the ascent, thinking they would penetrate to the bedrooms, and stayed below hammering on the lower door which only led to the basement, until an exasperated maid called ‘Come up.’ All this amused me a good deal more than it did the victims.”

“East side. 1902.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

“South Side 2219 St. Mary’s Avenue. 1902.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library. This southern elevation was actually the front of the home.

Miss Meliora’s hand drawn first floor plan of her home at 2219 St. Mary’s Avenue. Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

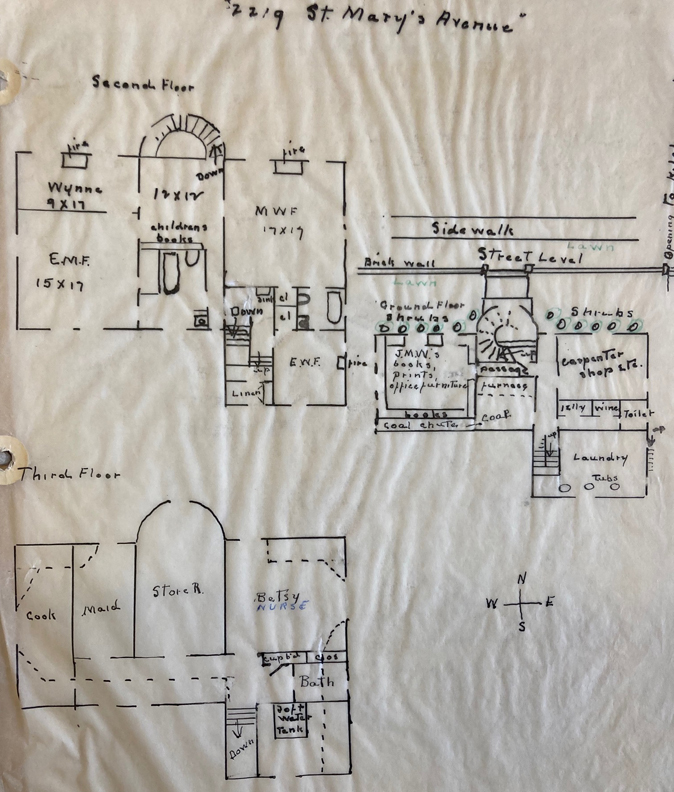

Miss Meliora’s hand drawn floor plans of her home at 2219 St. Mary’s Avenue. Included are second, third and basement plans. Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library. Note that “J. M. W.’s (her father’s) books, prints and office furniture” had a trickled over to her house at street level. I thought this might have been due to James Woolworth’s book addiction that we had learned of…but I later read:

“After my father’s death we had the empty room below the living room arranged as a library, with cream walls, dark woodwork and book cases around the room and curtains of a lovely brown and gold Japanese brocade, and in this room we put the rust and gold rug from his office, the office furniture which was very lovely Eastlake walnut, portraits of lawyers and all his books that came to me—a beautiful room.”

2219 St. Mary’s Avenue Interiors

I savored Meliora’s appraisal of her own residence, although I couldn’t help but notice the brevity– as compared to illumination of her parent’s home. Maybe she had worn herself out.

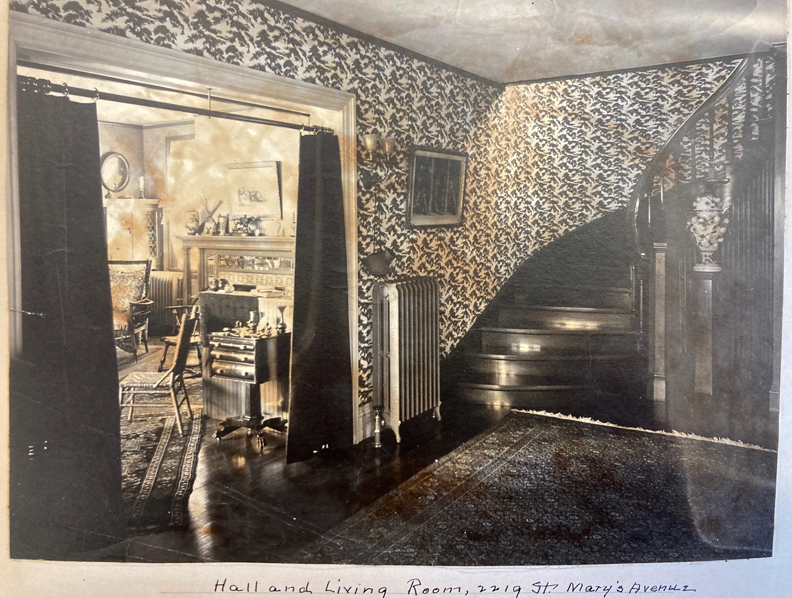

“Hall and Living Room, 2219 St. Mary’s Avenue.”

“The hall had white woodwork with a white paper covered with a pattern of pine boughs in dark bluish green and dark brown. When I went to the sixteenth century castle of the Shoguns in Kyoto I found this pattern painted on gold everywhere. The rug was the big blue and and red one, sixteen by eight feet which has been so much admired by lovers of fine rugs, a mahogany settee and my mother’s melodeon serving as a hall table. The pictures here and in the dining room were my mother’s lovely old line engravings and the fine mezzotint of Rembrandt Rabbi. In the small circle of the stair well was a white pedestal holding a big Dresden vase covered with flowers and birds.”

I know at this late hour I really shouldn’t be futzing about but I truly could not help it. I had to colorize the 1902 hallway, just because.

“Living room, 2219 St. Mary’s Avenue. 1902.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

“There were too many things in the room, according to the fashion of that time, until I possessed the furniture and pictures and other things from my father’s house, when I had developed taste enough to have fewer ornaments.”

“South end of Living Room, 2219 St. Mary’s Avenue.” Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

“The living room opposite was all green, walls and woodwork, with curtains at first of ruffled organdy and later of linen printed closely with all sorts of garden flowers. The mantel, designed by Mr. Kimball, had charming green and yellow tiles surrounded by narrow mirrors, and there were narrow mirrors filling the spaces between the three South windows.”

Image borrowed from Meliora Woolworth Fairfield’s archives. W. Dale Clark Library.

“It was a beautiful house, perfect for entering and comfortable for everyday living, though not a well planned one for the housekeeper, lacking as it did a coat closet and other conveniences that make for easy house-keeping. But if Mr. Kimball fell short in such matters, he was successful in the living quarters both in comfort and beauty and the outside was picturesque and unusual.”

Since Librarian Martha notified of the Woolworth cache, I have begun walking St. Mary’s Avenue sidewalks in my dreams. There are no cars. I’ve rung the Fairfield house bell. It echoed away into the distance and through all of those timber-clad rooms. The house sounded hollowed out and empty, although I haven’t gotten inside just yet.

An Afterword on Larsen

This possibly will not mean much to anyone but me and maybe nothing at all unless one has recently read “The Larsen Mystery” within “The Clue to Bircheknolle.” I came across Larsen and the death of a Little Andy Larsen in my study of the Woolworth compound. My stakeout led me to an Anton Larsen, long time domestic servant of the Woolworth family. To discover that Meliora included Larsen (not just included but wrote pages and pages on) in her memoir, even labeling him in the previous photo of the Woolworth grounds, piqued my interest—because he had certainly captivated me back in 2017.

“Larsen, of whom I have spoken so much, was a character, a tyrant, and a perfectly indispensable feature of our existence for twenty five years. He came to us at the Howard Street house when eighteen years of age, fresh from the Danish farms, unable to read or write, and ignorant of everything but the most elementary farm work. He at once went to night school and soon spoke English, read, wrote a good hand and knew enough arithmetic for all his needs. Where he learned to grow flowers I do not know, but he doubtless picked the brains of those who did, especially those of Donahue, the Clarkson’s gardener who, when he left them, set up the first florist’s shop and greenhouses in Omaha and was, with his sons, the leading firm of the kind for many years. In due time Larsen came to be a good carpenter and plumber and did most of the smaller repairs about the house. He built perfect replicas of the old and new houses for birdhouses. He had endless sisters and cousins many of whom began their careers as maids in our house. He had no style and saw no need of any and being of a sociable nature, was with difficulty restrained from friendly converse when driving. I think that was one reason he so disliked the brougham, in which he was totally cut off from any chance to talk. My mother cared nothing at all for conventions of this sort if they interfered with her convenience, and I have an idea that when she was alone in the surrey with Larsen an animated discourse about domestic affairs went on between them. I suffered acutely from all this, wishing we could make the stately progress of the Kountze or Patrick equipages in silent elegance, but my mother only said, ‘I had to tell Larsen—‘

Larsen was full of good reasons for not doing things that he thought superfluous. In time the vegetable garden disappeared, then the large flower border, and he tried hard to avoid washing the horses and carriages as soon as they came in, saying they would be dirty the next time they were used. Here the family was firm, and they were sent back to the barn if orders had not been obeyed. He hated to wear a livery in summer and would come out on a hot day in his work clothes with a disreputable old straw hat and mutter fiercely when sent to change. He really was, I suppose, overworked.”

Brilliant writing and if a quarter of it were true, I was along for the ride. Lo and behold, Meliora’s older, half sister, Jeanie, disparaged Larsen, as did James Woolworth, apparently. In fact Miss Meliora noted that when her mother died, Larsen lost his best friend in the home. Meliora did write some sharp things about Larsen, which I thought were deliciously snarky, until I discovered the family actually fired him. Larsen was understandably devastated and packed up and removed for work at the Union Pacific shop. It was all very surprising to me.

Anton Larsen, you’re A-OK in my book.

Obsessed with this part of town and still want more? Check out:

Mysteries of Omaha: 2226 Howard Street

Mysteries of Omaha: 2561 Douglas Street

For the Love of 2406 Farnam Street

Magnificent Obsession: 1928 Leavenworth Street

I welcome your feedback and comments. Let us hear from you. Please share your additional clues to the story in the “Comments,” as we know more together. Everyone would love to read what you have to say and it makes the sharing of Omaha history more fun. You can use an anonymous smokescreen name if need be.

You can keep up with my latest investigations by joining my email group. Click on “Contact” then look for “Sign me up for the Newsletter!” Enter your email address. You will get sent email updates every time I have written a new article. Also feel free to join My Omaha Obsession on Facebook. Thank you, Omaha friends. Miss Cassette

© Miss Cassette and myomahaobsession, 2022. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Miss Cassette and myomahaobsession with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

If you are looking for more architectural and Omaha history sleuthing fun, ask your local or bigbox bookseller for my new book: My Omaha Obsession: Searching for the City. Also available everywhere online. Thank you.

That those grand homes and others no longer exist is such a tragic loss of art and history. They are the landmarks that give a city its soul and unique identity. I only wish I had a knack for scriptwriting because the stories of early Omaha would give Julian Fellowes a run for his money.

What a treasure – “real history was speaking” and you were able to reach out and touch it, listen to it, and share it with us. Thank you.

What a treasure trove. Now we know much of the rest of the story. The house plans explain so much. From the descriptions of the parties they had I am surprised how small the rooms seem to house all those guests.

Fabulous article. I couldn’t stop reading. The pictures are priceless history. Thank you for sending me back in time.

Your sleuthing and reporting are such a gift to me. Putting faces and stories to the places I grew up. Thank you! xx

I may have overlooked what I’m about to ask about, but were the two homes demolished by the time she made all the floor plan drawings? Or was part of her motivation making them the hope they’d be saved?

For herself and those recognizing their importance and value, the feelings must have been visceral watching them being razed.

It was my interpretation that she drew up the plans to show what the houses’ lay outs once were–for her family’s records.