As I had mentioned in Park Avenue Recollection, when I first saw the building at 501 Park Avenue, evidently, I took no great interest in it. Carelessness on my part but there were many eyefuls in the surrounding neighborhood, which claimed my attention in those days. And even then, upon first formal meeting and further inspection, I was a bit taken aback.

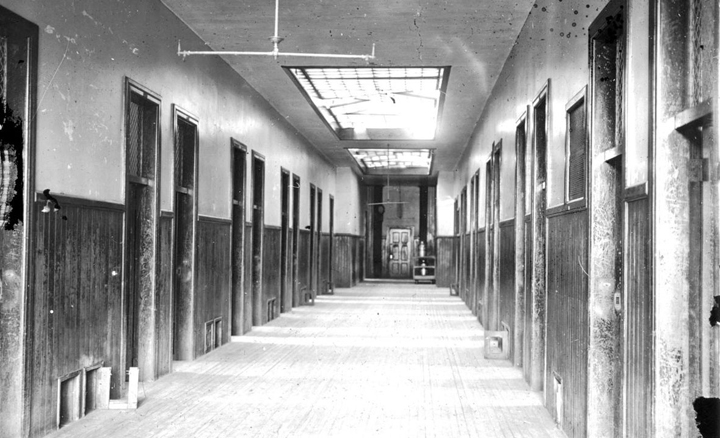

The first thing that comes to memory, as I think of it all of these years later, was the overpowering smell of chlorine and mildew—of musty wetness all around. Today I might have inquired about the odor but back then I was sweet and quiet and wouldn’t have known how to approach the unexpungeable stench. I recall the rental manager and I walked the hallways of what felt like an institution, an institution filled with all older, single males, superficially wandering or keying into doorways and briskly ducking inside. I felt so very uncomfortable in those halls. There was something terribly off. It seemed even the manager felt ill at ease with the proceedings and the inhabitants. The indoor swimming pool, from another time altogether, seemed to be centered lowly within the wings and offshoot halls, to recollection. I might be wrong on that account. A lifelong swimmer, the water and surrounding walls of this pool room did not give respite or call to me. In fact, I felt panicked and smothered in that large but shrinking room. This has always bothered me. Perhaps the ventilation was poor, I thought. Although I remember parts of the building being very interesting, the apartment offered me was on a lower level, in memory, and there were far too many things that felt trapped about the place. I slipped away quickly and continued my apartment search elsewhere.

Frightened might be a bit severe. Unsettled was probably the better word for my experience. Years later I would find out two of my friends had similar eerie, if not downright disturbing, experiences within this building. I will share those later in our investigation. The point being that on that dank, despairing day back in the early 1990s, I had no idea of what I was truly looking at when I toured the historic hospital turned health club. Now, so many years passed its razing, even as I type, I imagine the original structure and her people regard me gravely from the great beyond, “Well, well, well… Weren’t we worth waiting for?” The answer is yes.

I had pledged a proper investigation into the curious hospital-health club-apartment building when we last gathered, and now you may as well know, I had also made a vow to the historic building and her humans as well. I am Irish, you understand, so this is a wake, of sorts. Yes, for a building. I should explain to newcomers that we have an arrangement at these vigils: I will get all dreamy and give way too many details and not always the particulars that some of folks might want and then The Initiated Columbos will soak it up, add to it, question, gather more data or move on with a snort. The purpose being, that at some point, we might want to remember what building was at 501 Park Avenue before SPACES came to be. For others among us, the old hospital and her people already have a place in our rather crowded, memory files. I say let us draw up all that we can. So let’s take off in that direction without delay. For those of you who like prescribed beginnings, please review our previous installment: Park Avenue Recollection. Some of you rather like slipping down slopes without formal induction and we welcome you also.

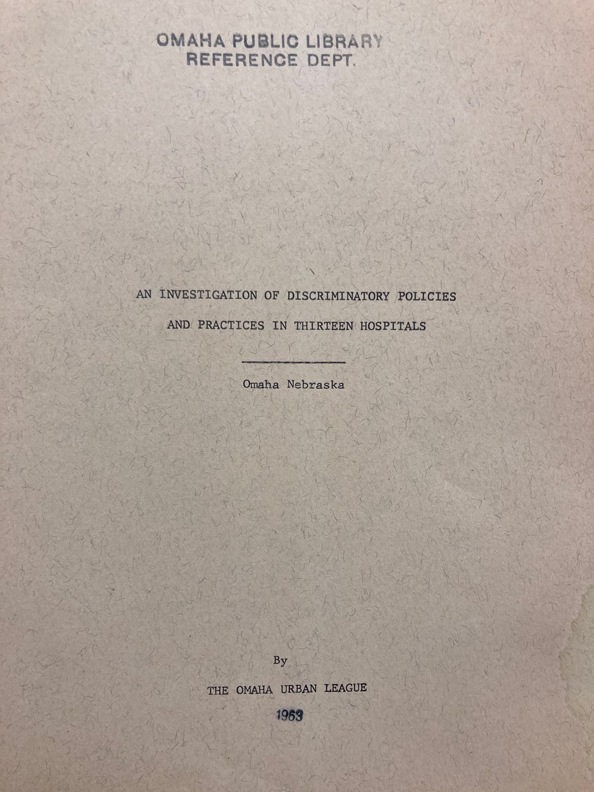

Investigation at a Glance:

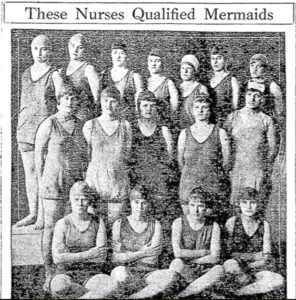

Long a Park Avenue devotee, a chance encounter with the Park Ave Health Club and Apartments in the early 1990s spurred my hunt to unravel the unusual origins of this strange building. Readers are given exclusive entry to the privately run Nicholas Senn Hospital. Follow along the twisting path to meet its founders and the story behind their Field Club mansion, a mysterious death, the mermaid nurses and daughters, the Doctors Hospital, lingering spirits, memories and Omaha lore.

Hanscom Park and the Park Avenue District

I believe the Park Avenue neighborhood began with the development of Hanscom Park. The origins of multiple neighborhoods seemed to follow creation of this significant park—at least these are my suspicions after a lengthy time on this beat, a lot of which was just spent wandering around and whistling and daydreaming. Admittedly, I did crack some books and sniff in the archival newspapers for dates and the overall tone of the times. As always, I am open to anyone else’s theories.

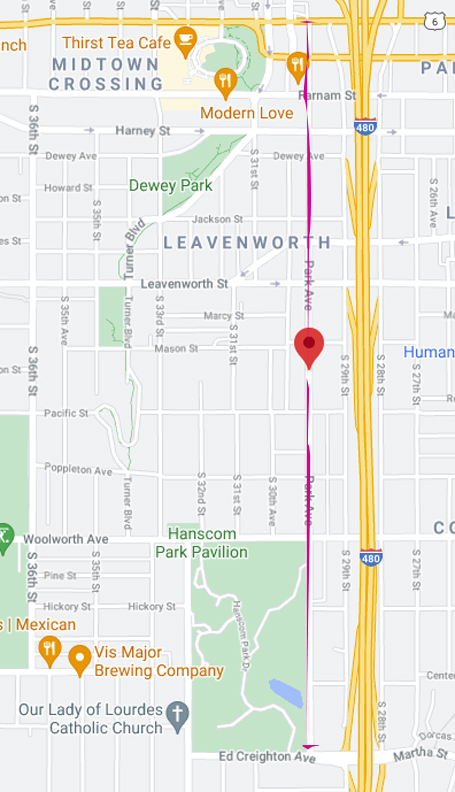

Hot pink line marks Park Avenue as it runs north-south, a short fourteen blocks from Ed Creighton Avenue on the southern border of Hanscom Park to its northern conclusion at Dodge. North is shown at the top of the image. Park Avenue is, interestingly, only one-way from St. Mary’s Avenue north to its endcap at Dodge. Image borrowed from Google Map.

Hanscom Park is the oldest existing public park in Omaha; there is a large, historic neighborhood also called Hanscom Park, directly to its south and west. The public park itself is comprised of 57.7 acres, clockwise from Woolworth Avenue on the north side to Park Avenue, Ed Creighton Avenue on the southern edge to western 32nd Avenue. Andrew Jackson Hanscom and James Gabriel Megeath donated the land to the city in 1872. We’ll get into Mr. Hanscom in a bit but Mr. Megeath was said to have purchased upward of 380 acres of land in his early Omaha days as a pioneer general merchandiser at his Megeath & Co. His follow-up act found Megeath at the head of a very successful company, developed as a secondary business to the new Union Pacific Railroad. Megeath’s enterprise engaged as a forwarding company, organizing shipments to folks across the country or other corporations; his business was said to have handled the bulk of forwarding freight through the UP, making Mr. Megeath a very wealthy man. At the time of Hanscom and Megeath’s generous donation, the large tract was “situated in what was then the extreme southwest portion of Omaha, was a wilderness of hazel brush and natural forest trees.”

A pavilion at Hanscom Park. It has a large wrap-around porch and balcony and is partially blocked by trees. There are people sitting on the steps of the pavilion. There is part of a path in the bottom left corner. Creator: Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). Publisher: The Durham Museum. Date: Photo possibly from the Fall of 1913.

From World-Herald archives, it would appear that the Hanscom Park grounds were first opened up as a public space in 1879 but it wasn’t until 1889, according to the Federal Writers’ Project, that Hanscom Park was formally landscaped and park facilities added. Through the dense History of Omaha and South Omaha by Savage and Bell, I would learn of the peculiar financial particulars in this plan. (And maybe this is quite normal–Miss Cassette is not known for her business mindedness). “No charge was made for the property, but the gift was upon condition that the city expend in improving it the sum of three thousand dollars in 1873.” There were differing dollar amounts for different years, at times increasing to continue “to forever keep the property in good order…” The book also divulged it was reputed landscape architect, Horace William Shaler Cleveland who designed the park’s natural, rolling, wooded look. (Cleveland is also responsible for Omaha’s Parks and Boulevards System. Check out my Dundee Sunks investigation for more on Cleveland.) I was fascinated to get an early view of Hanscom Park through the eyes of Edward Francis Morearty’s despairingly humorous Omaha Memories, published in 1917: “The city hired a park keeper at Hansom, who was paid a meager salary in addition to free house rent; the only ornaments worthy of note in the park up to 1890 were two cadaverous bald eagles, disgustingly devouring raw meats. On the east entrance to this park was an arch sign, which read, ‘Nature Designs and Art Improves;’ this old adage no doubt has been read by many who visited that park in the early ‘80s. If nature in its crude form ever needed the touch of art, that park certainly did.”

I am of the belief that Hanscom Park’s undulating, pastoral areas and winding paths are its most highly developed characteristics and are of superb design to this day. This clever arrangement creates separate vignettes and tranquil escapes. Around each curve allows park-goers a sense of privacy and serenity, while easily sharing the space with many other guests. Interesting to find that Cleveland laid this out. It is a divine place. I particularly love the dark view from the corner of Park Ave and Woolworth. The haunting depth of trees from that drop-off!

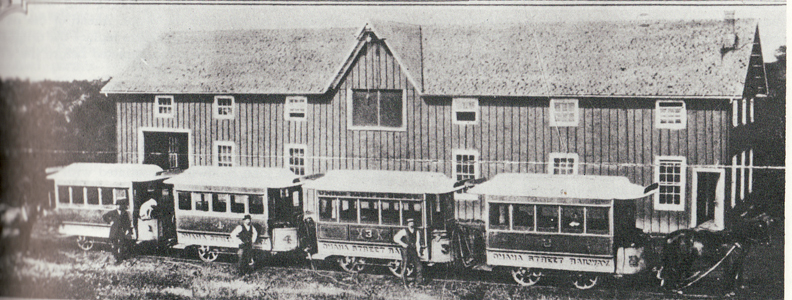

Richard Orr’s engrossing O & CB Streetcars of Omaha and Council Bluffs revealed that the carbarn and stables of the “Hanscom Park (streetcar) line” were built on the northeast corner of Park Avenue and Woolworth. One of his Omaha Horse Railway maps of 1881-1882 showed many Omaha streets already platted along the streetcar line “but many west of 24th were still cornfields or wooded areas and had not been opened.” Imagine the view from an early horse driven car.

Photograph borrowed from O & CB Streetcars of Omaha and Council Bluffs. 1882. “Bobtail cars 1, 4, 3 and 2, the first ones assigned to the Hanscom Park line, line up with their drivers and/or horses on the west side of the new stable and carbarn at Park and Woolworth Avenues.” Orr’s research showed that fifty customers could be transported in this fashion.

The lower lake at Hanscom Park. Creator: Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). Publisher: The Durham Museum. Date: 1916.

By 1898 Hanscom Park had two lakes, a cascade, flowerbeds, and fountains. At the time of the Federal Writers’ Project New Deal era survey, (found in the amazing American Guide Series: Omaha: A Guide to the City and Environs), Hanscom Park offered a bandstand with musical concerts paid for by the Park Board and Street Railway Company, a lagoon, a lake, tennis courts, a Spanish cannon, a large pavilion, and multiple playgrounds. “Northward, skirting Thirty-second Avenue, are greenhouses and a conservatory housing rare tropical plants—a gift of Mrs. George A. Joslyn.” At the time of the survey, Hanscom was second only to Omaha’s oldest park, Jefferson Square.

In a recent conversation with Chris McClellan, owner of Blue Line Coffee in Dundee, I only just learned of Jefferson Square. Chris educated that Jefferson Square had been an original Omaha park, if not the first. Once I set about to ferreting, I would find some discrepancies in dates. From what I could make out, the Jefferson Square land, located between Cass and Chicago Streets, 15th and 16th Streets, was “set aside” for a park in 1854. Its southwest corner became site of Omaha’s first public school, built in 1863. Jefferson Square was most definitely a functioning park by 1865. By the late 1930s- early 1940s, the Federal Writers’ Project survey made a point to snip Jefferson Square was “almost wholly a retreat for hoboes and the only recreations indulged are smoking, resting, swapping yarns and scratching.” Perhaps because of this public besmirching or other behind closed doors plans, the Jefferson Square Park was regrettably torn down in 1969 to make way for Interstate 480.

Jefferson Square Park as seen downtown in better days. I am a big fan of anything involving stanchions and chains. Creator: Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). Date unknown.

I first found evidence of real estate parcels opening up along Park Avenue by 1879. By year alone this real estate opportunity seemed to square with the informal opening of Hanscom Park. Mr. George Pickering Bemis, was a big real estate agent in town and from his “Bemis Column of Bargains” perch in the World-Herald, he would market “the finest residence lots in the city.” Terrace Addition was the latest development Bemis exhaustively promoted, “on the road to Hanscom Park.” A current survey of the Douglas County Assesor’s site revealed the Terrace Addition is comprised of twenty parcels along Park Avenue and 29th Street between Leavenworth and Mason. Bemis’ 1880 pronouncement described forty lots on Park Avenue and Georgia Street, “from $125 to $300. Seven years time at eight per cent. Interest to those who will put up good buildings. For further particulars apply to Geo. P. Bemis. Fifteenth and Douglas streets.” He urged, “Call and examine plats and post yourself up.” He could also be found in the 1880s transmitting from the Omaha Daily Bee. George Bemis was known as an early promoter of Omaha public parks, would go on to become mayor of Omaha and develop his own subdivision, the desirable Bemis Park Landmark Heritage District.

We had previously discovered in Chapter One of this ever growing tale, that Park Avenue was considered the western most fringe of Omaha in those days. The Streets of Omaha: Their Origins and Changes offered major clue that Park Avenue was long ago “officially changed to 29th Street, but due to popularity, retained its original name.” 29th Street extends both north and south throughout Omaha but maintains the Park Avenue name in this distinct area. Also worth re-mentioning–29th Street was once called Georgia Avenue, named in honor of Georgia Hanscom, daughter of Andrew Jackson Hanscom.

I found it interesting that the wealthy Andrew Hanscom family lived in the original downtown Paxton Hotel, apparently an apartment hotel for a handful of well to do Omaha families. Mr. Hanscom was known widely as an early Omaha attorney, a real estate broker and Nebraska Territory’s speaker of the first House of Representatives. In 1873, the year after Hanscom donated his soon to be namesake park to the city, he purchased controlling interest of the Omaha Street Railway Company. He later sold it off. Richard Orr estimated in his deep dig streetcar tome that Hanscom lasted only six months in his position as president of the Omaha Horse Railway. The World-Herald let on that in the summer of 1885 there was a specific “Park Avenue Street Car,” which “left the park every ten minutes.” They were referring to Hanscom Park. Interestingly Richard Orr called this the Hanscom Park line; Chris McClellan of Blue Line Coffee tipped me off that this later transitioned to the Green Line. Most Omahans still lived in downtown, north and south along the river, and in neighborhoods east of newly established Park Avenue. Evidently this constant streetcar was shuttling park lovers to Hanscom round the clock. I smiled to read that after 8:10pm, the rotation lagged to twenty-minute increments. Even still, that meant a tremendous amount of Omahans were traveling frequently to the new Hanscom oasis at all hours. As previously mentioned this Railway Company was later sponsoring Hanscom Park concerts. At any rate the continuous, convenient, transportation ensured the public park was being enjoyed and would be worth the investment to the city.

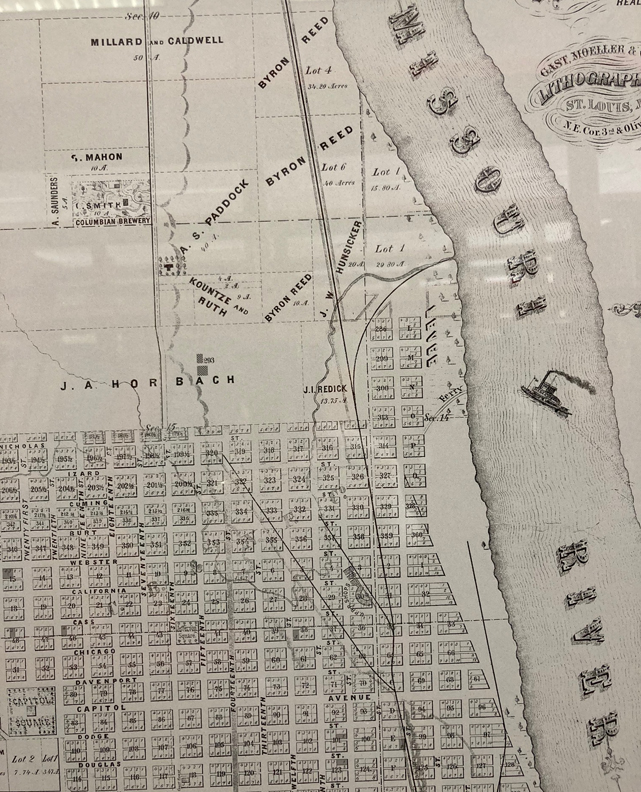

Great framed map down at the W. Dale Clark Library. 1866 map of Omaha. Twenty-first Street is the furthest west thoroughfare, at least that my photo captured. Can you spy full city block Jefferson Square? There is also a Capitol Square depicted.

I love this one. Glorious flowerbed designs, trees and the park conservatory-greenhouse at Hanscom Park. Creator: Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). Publisher: The Durham Museum. Date: 1917.

Larger tracts of land were being platted and divided into parcels all along Park Avenue in the early 1880s. The subdivisions comprising what I am calling the Park Avenue District were Hanscom Place, Rees Place, Terrace Addition, McCormick’s Addition and the Boggs & Hills Second Addition. As mentioned in the first chapter, many of the original grand houses, apartment buildings, duplexes and row houses of these early developments are still standing strong. Let’s move to the northern end of Park Avenue at Dewey so we can focus in on another one of these historic additions.

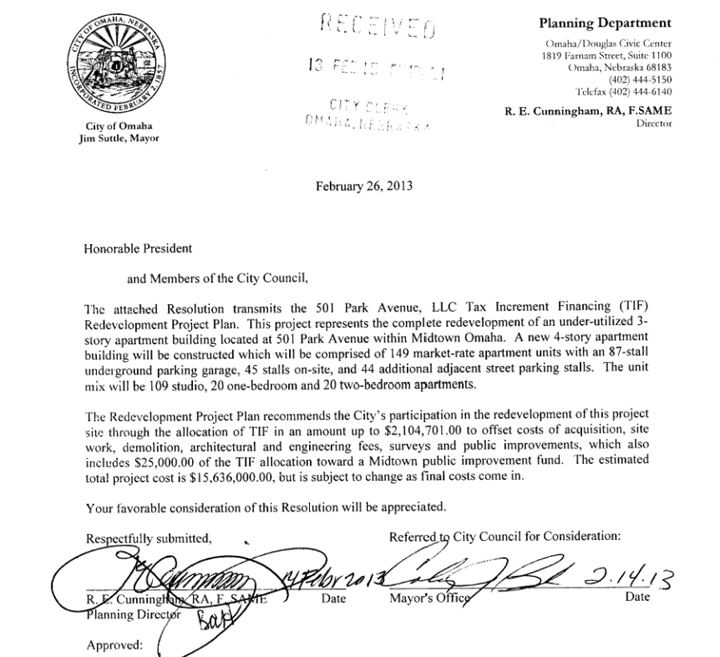

501 Park Avenue, on the southeastern corner of Park Avenue and Dewey Avenue, is now home to Bluestone’s $15 million SPACES apartment complex, built in 2014. But back in the late 1870s, Mr. John Redick owned this land. I’ve got to estimate Redick took into account the new Hanscom Park down the way when he drew up real estate plans for his John I. Redicks Subdivision. This corner, a lot within his subdivision, would later become the building site for the mysterious hospital of our fixation. Above photograph displays a portion of the west elevation of SPACES, running along Park Avenue. The second photo shows the north elevation of the SPACES building, parallel to Dewey Avenue.

John I. Redick

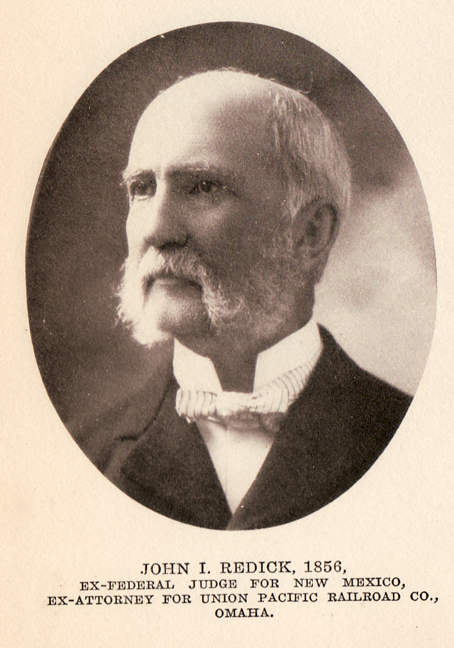

Purportedly Judge John Redick moved to Omaha in 1856 as an attorney. Arthur Cooper Wakeley’s massive Omaha: The Gate City and Douglas County Vol II stated that among men who figured prominently during the first half century of the city’s existence, none was better known than Honorable John Irvin Redick. Besides a well known attorney and jurist, Redick was an early real estate developer and businessman, known for building and railroad investment. Redick is one of those Omaha surnames that one will find sprinkled high and low throughout town. Redick Avenue; Redick Mansion turned Hall; I hadn’t heard of the Redick Opera House of yesteryear but most everyone has eyeballed and adored the cool Art Deco Redick Tower at 1504 Harney Street. I would discover in this stakeout that Judge Redick platted Redicks-Clark, Redicks Park, Redicks Grove, J. I. Redicks Subdivision and Redicks Second Addition subdivisions, possibly more–those are just the ones he named after himself. We can see one of his developments north of downtown in the 1866 map displayed earlier.

Great photo of Judge Redick scanned from Nebraskans 1854-1904 by Bee Publishing Co. 1904. One of my favorite treasures, this particular book was added to the Genealogical Society Library of the Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records in 1938, a donation of a William Stebbing. It was withdrawn from the library in 2002 and I came to own it a few years back.

As an interesting side note and testament to how busy folks were back then, Omaha: The Gate City tracked Mr. Redick living in Denver in 1877, where he served as attorney for the Union Pacific Railways. He returned to Omaha in about a year. By 1887 Redick had moved to Los Angeles where he was president of the Southern California National Bank until he returned to Omaha again in 1889. Through these moves I discovered Redick buying and selling Omaha land…or was his wife making these acquisitions?

A community favorite, the 11-story, buff brick Redick Tower was built in 1930 for the Garnett & Agor Company as an office building; Omaha architect, Joseph G. McArthur designed it “as an art deco skyscraper.” The Garnett & Agor Company curiously named their building for the Redick family because the Redicks had owned the land the Modern structure was built on since the 1870s. (Coincidentally the very time period Redick was readying to plat his rural land along Park Avenue.) I would learn from the fantastic Omaha City Architecture, published in 1977 by Landmarks, Inc and the Junior League, that by the mid-30’s the downtown structure was purchased by the Redick Tower Corporation. It is now a hotel. I love this 1970s photo by Lynn Meyer, featuring Mickey’s Night Club (go-go bar I’ve mentioned before) on the first floor. Camera faces the southeast corner. Image borrowed from one of my personal favs: Omaha City Architecture.

The first J. I Redicks Subdivision (before the replat) encapsulated buildings from Dewey Avenue on the north to 27th Street on the east with a southern border of Leavenworth to 31st Street on the west. I suspect I-80 had stolen a chunk of this original development. The early deed book (thanks to Mary B. at the Douglas County Register of Deeds office!) log for John I Redicks Subdivision show “Redick and wife” first began selling parcels as early as 1881. 1883 advertisements in the Omaha Daily Bee boasted of Redick’s “Elegant Building Sites.” By 1887 there were “Two lots and ten-room house in J. I. Redicks Sub-division at $7,500.”

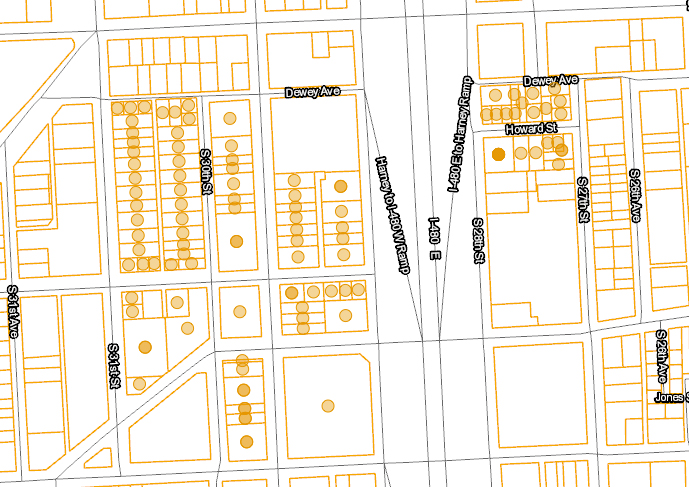

Image borrowed from the Douglas County Assessor’s site. Orange dots represent current parcels within the J. I. Redicks Subdivision. You will notice that the large parcel where the SPACES apartments now sit is no longer within the Redicks subdivision.

Specific Notes for Snoops

This next portion might be a bit technical and unpleasant for some. I haven’t gotten this specific in a while but some of you enjoy the process as much as I do, some just like getting in the mortar and others have written, asking how to begin doing their own house history research. If you don’t like these deed and boundaryline particulars, skip on to the next section and we’ll catch up with you later.

The SPACES apartment complex at 501 Park Avenue, former site of the hospital we are investigating, is now within the Brando Subdivision name. A visit to the Douglas County Assessor’s website, a tool I use religiously, will divulge such information. A person can enter in a specific address, if known, or scour the county map for the parcel in question. Once located and the “report” is opened, look for the “Legal Description.” In this case: BRANDO LOT 1 BLOCK 0. I figured this had to be a renaming of the original addition name after clicking on all surrounding historic extant parcels and finding they were all still within the J. I. Redicks Subdivision. In this case, I surmised 501 Park Avenue had originally been under J. I. Redicks and it was, but if, by chance, it was in another addition’s name altogether, the legal description would allow a person to trace it back to whatever it had been previously. This is key and anyone at the county offices will need this legal info in order to help you. That is, if you get stumped and need to ask questions. As we know around these parts, addresses strangely change over time. It has been explained to me that Legal Descriptions are not finite but are at least traceable. I am not exactly sure why but I have found it is common for a new building or development company to rename a historic subdivision name into something new fangled. For example the Christensens of Bluestone Development put their SPACES complex under the 501 Park Avenue LLC and Brando Lot I Block 0 replaced the earlier Legal Description of J. I Redicks Subdivision Lots 14, 15 and 16 of Block 5 in 2014. Clear as mud? I have begun to love this stuff and have only picked it up thanks to the great workers at the Register of Deeds and Assessors offices. It does get easier with practice.

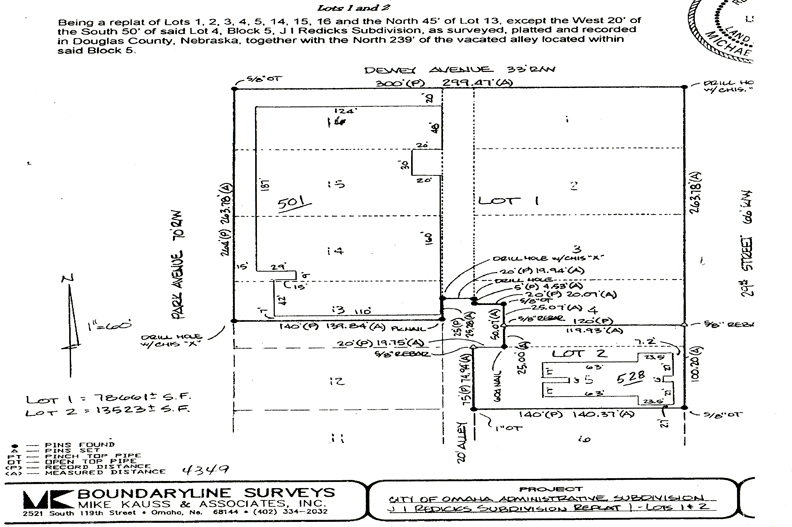

Not surprisingly the old hospital would grow over time and swallow up surrounding parcels. Mary, from the Deeds office, was able to find this cool J. I. Redicks Subdivision Replat boundaryline survey map, which I love. Thanks to the past work of Mike Kauss & Associates, we can see a replat was made to include a new Lot 1 and 2. The original lot numbers are written faintly beneath. I believe this was from the time that the Park Avenue Health Club parking lot was created to the east. There is a good deal that I don’t understand on this map and honestly, we don’t need to figure everything out here in order to gather some useful data. The discovery that the original hospital, which I knew to be at “501” was comprised of lots 13, 14, 15, and 16, potentially more. This gave me a starting point. The clues do not usually come in order, so you just gather everything you can find. At this backward point, I had a solid idea of the correct, historic lots and block name and I was able to begin ferreting through the correct deeds book.

On With the Stakeout

Through the deeds book, I observed “John I. Redick and wife” sold Lot 14, 15 and 16 of Block 5 to Charles Shiverick in June of 1885. (Snoops from the previous section, note that Lot 13 was not included in this parcel grouping initially.) Ella C. Shiverick then moved the parcels into the Shiverick Furniture Company name in 1899. Charles Shiverick & Co was one of the earliest furniture dealers in Omaha; they’d operated out of a number of different locations in downtown Omaha but I never found that the family business openly advertised a showroom or warehouse at this Park Ave.-Dewey Ave. location. Perhaps they had an early residence there or maybe it was an investment in the new hot area or plans to make a showroom there? It is interesting to consider, of the extant structures surrounding this mystery corner, the oldest ones are housing from the years 1888 and 1889.

Charles and wife Eleanor “Ella” Crary Shiverick had four children; the couple were members of two of Omaha’s oldest families. Years later the Shivericks had a posh residence at 38th and Jones, in the yummy part of the West Farnam District. Ella would go on to live at the Blackstone Hotel after husband Charles died in 1929. I always have to throw that in, if you’ve noticed—since my lifelong obsession with residential hotels after seeing My Bodyguard, as a kid.

The deed for Lots 14, 15 and 16 somehow got into the hands of the “Treasurer.” We have seen this curiosity before. Often called a treasurers deed, it can mean that the buyer acquired the property from the county. In this case, the treasurer sold the trio of lots to Richard L. Baker in May of 1911. Because both of the Shivericks were still alive at that time, I was confused. It turns out there was a 1903 filing that brought amended articles of incorporation announcing Shiverick Furniture Company was changed to the Baker Furniture Company. Further digging found a couple of court cases of Baker against Shiverick, Shiverick against Baker, which involved dispute over stocks and capital monies in the transition of the company. The Omaha Carpet Company merged with the Baker company in that time period and by April of 1910, a Mr. Roseborough and Mr. Dansken became the new business owners. Even though I could never actually locate a building to the Park-Dewey corner, the Baker Furniture Company held the deed until 1916. A few other names were logged on the deed to include the Redick Realty Company, which has me believing it was back in our man John I Redick’s folio. By June of 1917 William Condon sold the three lots to Albert P. Condon. And that, dear friends, is where our story really begins.

Origins of the Nicholas Senn Hospital

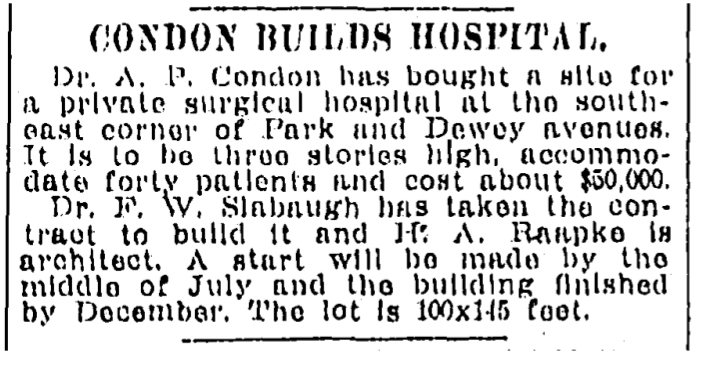

The first mention of the hospital building at 501 Park Avenue came in the summer of 1911 with this World-Herald piece. These are the kinds of articles ((we)) live for when gathering clues because the architect, builder and owner names are divulged. It isn’t usually this clear.

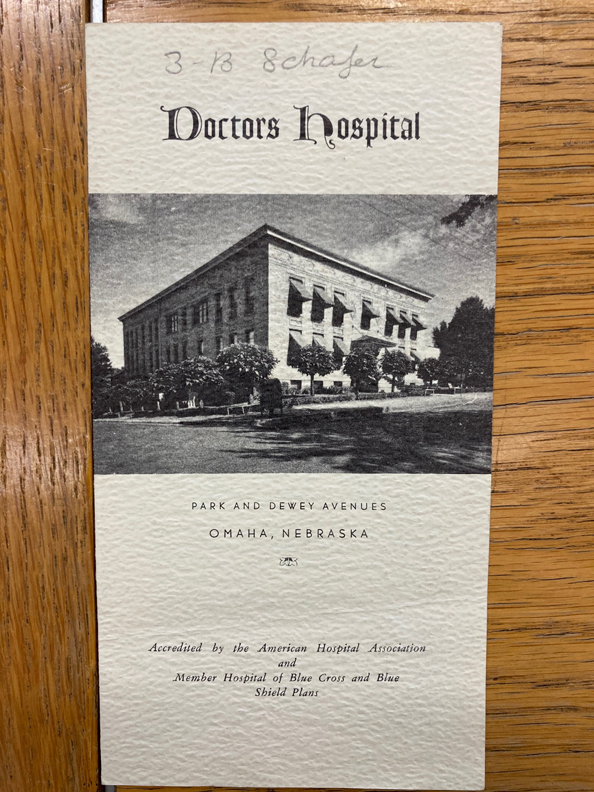

Image borrowed from OWH June 29, 1911: Dr. A. P. Condon bought a site for a surgical hospital on the southeast corner of Park and Dewey avenues. Three stories high, accommodating forty patients and would cost $50,000. The paper mentioned that building would begin in July 1911, with completion by December. I had already taken note of the name Albert P. Condon entered on the deed in 1917, so I found it odd that the same fellow would have forked out to build the hospital back in 1911 before owning the land. Then again another Condon sold it to him, so I figured it must have been a family operation.

Henry Raapke

We have come across both the Slabaugh and Raapke names in our past obsessions. Henry A. Raapke was a noted Omaha architect who worked in the city for about 50 years. After experiences in Italy, France, Greece, Germany, Switzerland, Holland and Belgium, following a four-year stint with Thomas Rogers Kimball, Mr. Henry Raapke would return to Omaha in 1908. From the Nebraska Historical Society, it would appear Raapke designed a number of residences before his hospital project for Dr. Condon. For those inquiring minds, check out these sites focused on all things Henry Raapke.

https://unomaha.omeka.net/exhibits/show/raapke

http://www.e-nebraskahistory.org/index.php?title=Henry_A._Raapke_%281876-1959%29,_Architect

Henry Raapke 1939. Photo borrowed from the Nebraska State Historical Society. Possibly the best architect photo I’ve ever seen, what with the story that grainy, pitted image tells. Raapke looks like one of the New Yorker Magazine editors from the forties or a hinky freelance street corner writer. These are compliments–I tip my hat.

The Beautiful Neighbors

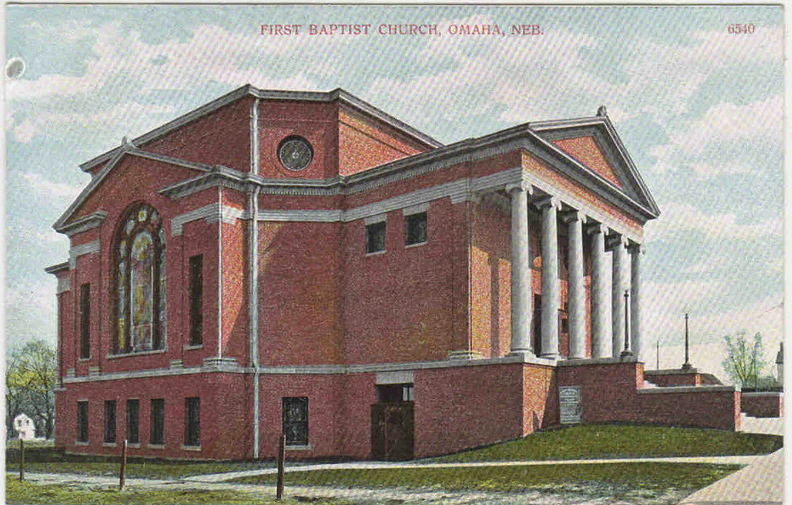

At the time of the hospital’s announcement, there was already an impressive feat of architecture right across Dewey Avenue to the north. As an aside–according to Brick’s The Streets of Omaha: Their Origins and Changes, “Dewey Avenue was named in honor of Charles H. Dewey of Dewey & Stone, pioneer Omaha merchants.” (You may want to scratch this down in your pad as this clue figures in later.) Brick noted Dewey Ave. was renamed from the odd fitting, Half-Howard Street. The architectural feat was none other than the First Baptist Church, on the southeast corner of Park Avenue and Harney or northeast corner of Park Avenue and Dewey, your preference. The church had been built and was serving its congregation in 1904. I figured the rest of the Park Avenue neighborhood was chockablock in large residential, single and multifamily buildings, based on the build dates of most extant structures. An impressive structure in the Classical Revival style, the First Baptist Church was designed by architect, John McDonald. John and Alan McDonald designed a parish and social building, or Sunday School addition, in 1925 with further updates in the forties.

Great postcards, both from 1910. Camera is facing at a southeast angle. This view abuts Harney Street. The 1904 church cost $44,500 to build.

Front exterior view of First Baptist Church. It has six pillars and two lampposts in front of it. Located at 401 Park Avenue. Creator: Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). Publisher: The Durham Museum. Date: 1900-1910.

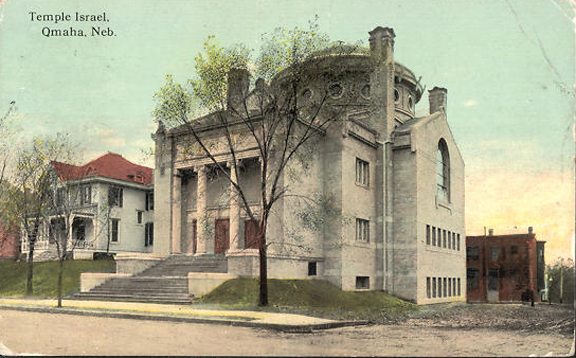

Another formidable anchor on the southern end of the J. I Redicks Subdivision was the gorgeous Temple Israel on the southwest corner of Park Avenue and Jackson Street. The temple was built back in 1907-08, according to Omaha: A Guide to the City and Environs. An Inventory of Historic Omaha Buildings identified its architect as the influential John Latenser. This place of worship has been known as St. Johns Greek Orthodox Church my whole life, but it was that large ornamental dome that really captured my attention.

The exterior of Temple Israel, located at 604 Park Avenue. Love the glimpse of the rowhouses in the block to the west. Creator: Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). Publisher: The Durham Museum. Date: 1925.

Temple Israel painted postcard from 1913.

Temple Israel (602 Park Avenue, sometimes assigned 604 Park Avenue) and its neighboring houses, now gone, from 1908. I shared this one previously but let’s have another look. It gives a great feel for what the neighborhood once was. Creator: Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). Publisher: The Durham Museum.

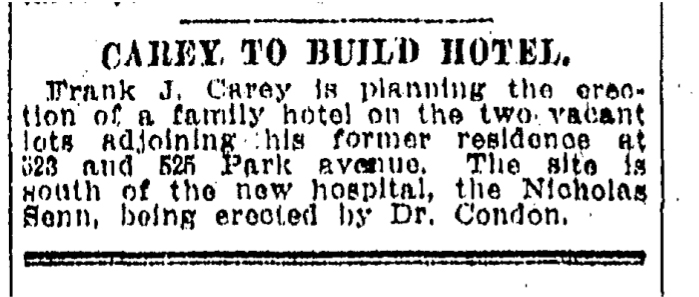

Meanwhile neighbor Frank Carey would spring from the coattails of the newly announced Condon hospital and advance his plans for nearby “family hotel.” I discovered Frank Carey was a hotel and laundry owner who continued to buy property around town. His name would come up again years later in the hospital case. Image from the OWH. 1911.

Raapke would have his work cut out for him.

Nicholas Senn

Dr. Albert P. Condon was a local physician in private practice. To quote the University of Nebraska Medical Center site, Condon’s hospital “was built as an investment and expansion” of his established practice. We will probe our Condon files in a bit (and also those of his wife, who often remained in the shadows) but first– the curious naming of his hospital.

Albert Condon named his Omaha hospital Nicholas Senn for the late-19th century surgeon who had also been his professor of surgery at Rush Medical College in Chicago, Illinois. Aside from being a mentor, Senn and Condon might have enjoyed a friendship. (I have no proof of this.) Dr. Senn was esteemed in the medical and military communities. Born in Switzerland in 1844, Senn lived the majority of his life in the United States Midwest until his 1908 death. He was venerated as an American surgeon and professor, involved in experimental research of acute pancreatitis, head and neck oncology, the intestinal tract, plastic surgery and the treatment of leukemia with x-rays. Senn authored many books and was reputed for his comprehensive, personal library of medical books, journals and archives. He founded the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States and later served as President of the American Surgical Association. One year before faithful student, Dr. Condon, named his hospital for his mentor, the Senn High School in Chicago was built in honor of the surgeon.

- Nicholas Senn in 1904 from Physicians Surgeons Medicine.

- Nicholas Senn in military uniform.

- Senn conducts a surgical clinic for medical students, 1895.

Nicholas Senn Hospital

Throughout my research, I discovered the Nicholas Senn Hospital was often mistakenly recorded as having opened in 1916 but the hospital actually admitted its first patients in January of 1912. The Gate City and Douglas County said opening day was February 1, 1912, but who’s splitting hairs? It is fascinating how many private hospitals existed in Omaha’s early years, extensions of numerous doctors’ own practices, as well as other specialty hospitals such as the Omaha Maternity Hospital, the City Emergency Hospital and the Douglas County Hospital. How could one hope to keep a private hospital afloat? Because of limited finances, most of these private hospitals did not stay in business for long. I was intrigued to see Nicholas Senn Hospital Association of Omaha was organized straight away as a charitable hospital. By June 16, 1916, the hospital association was dissolved and Nicholas Senn Hospital was re-organized as a non-profit charitable corporation, which is possibly why some historians thought it opened in that year. At that time Senn Hospital announced their plans to inaugurate “a large charity ward” to “render free medical and surgical care to indigent patients.” I will not pretend to fully understand what all of these distinctions meant.

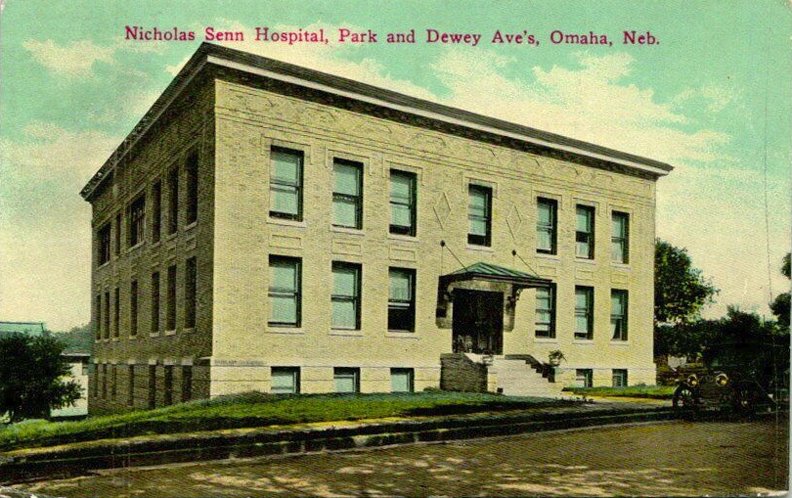

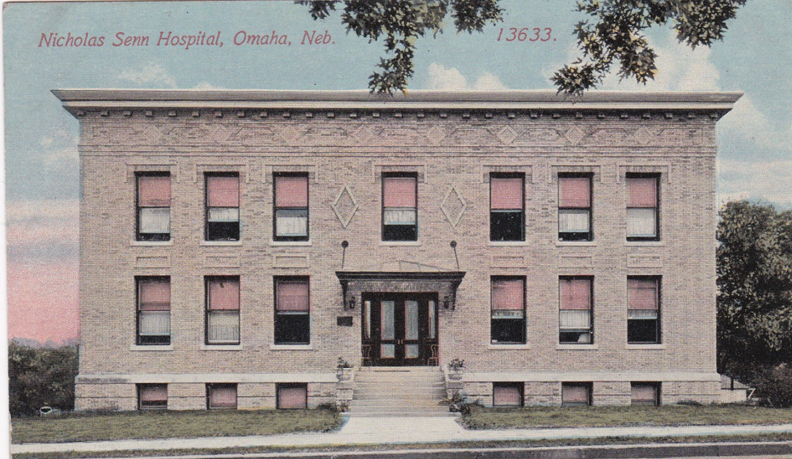

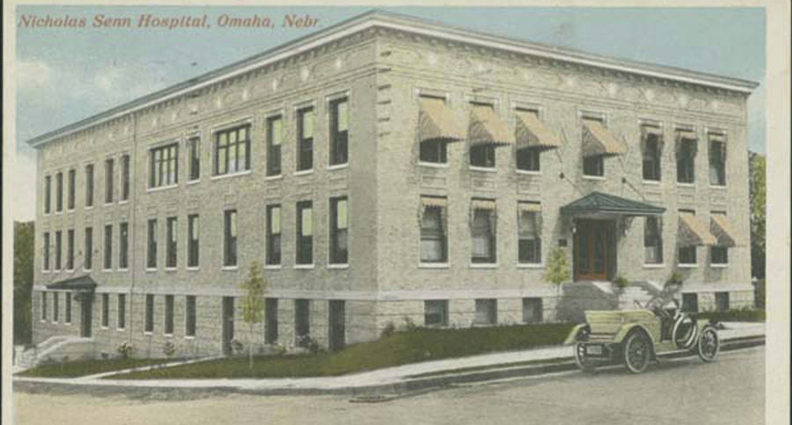

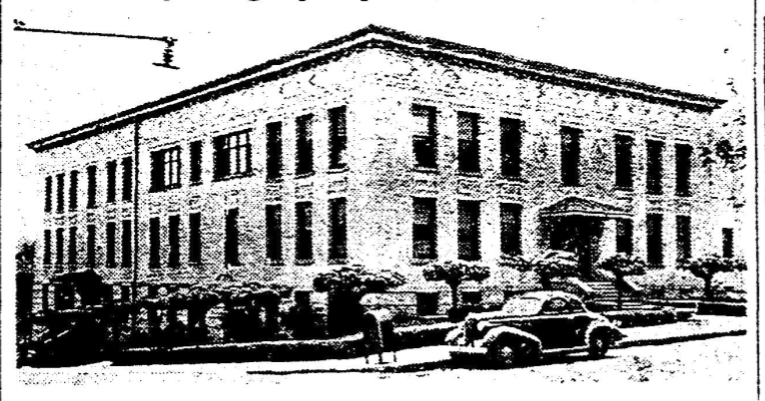

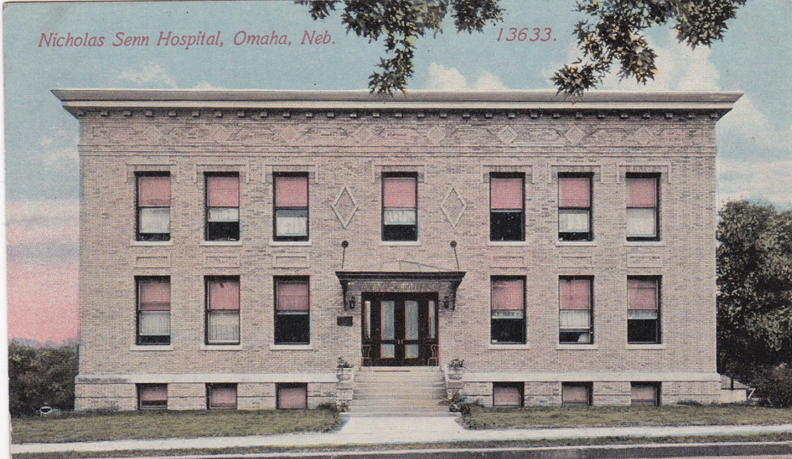

The earliest photo I could find for Nicholas Senn Hospital is this great postcard on Ebay. It is labeled 1913. I tend to believe this date is correct, because there is not yet an entrance door on the north (Dewey Ave) side at this point.

As we can observe, the original Nicholas Senn Hospital was a smaller-medium sized building of a simple, practical design. A respectable eclectic revival style, the brick hospital could have easily been an office building downtown or a library. Raapke’s design sent a serious, ordered message. The exterior masonry finishes were quite nice but not too showy. Perfect for a private hospital. Durable, fireproof. He used many classical touches—such as those peeking dentils underneath that proper cornice or is that a modillion under the cornice? The brickwork and inlaid patterns are well-composed. I admire the clean look. The buff brick was said to initially have “a green metal marquee overhanging double doors.” It is important to consider that although modest to our eyes, this was a thoroughly modern looking building in its day—this at a time when many local hospitals cared for their patients within the walls of old (amazing) mansions. It is also interesting to weigh in the formal Nicholas Senn Hospital plunked down within a residential neighborhood.

I would find that within months the hospital experienced its first celebratory births (early on it was noted the hospital didn’t even have a nursery and newborns were put in baskets in their mothers’ rooms, which sounds like a healthy, beautiful solution to me but didn’t they just have multiple-bed wards in those day?) and deaths of their initial patients, successful surgeries and all triumphs known to modern medicine including the completion of nursing classes. Yes, Nicholas Senn had their very own nurses “training school.” They offered an in-house nurses’ training program that many a mother and grandmother of Old Omaha graduated from. More on that later. A fire in the Nichols Senn elevator shaft in April of 1912 quite possibly scared the 35 new patients, let alone all of Omaha. But local stories of medical marvels like the recovery of 1913 tornado victim, Grace Slabaugh, “daughter of Judge W. W. Slabaugh, former high school tennis champion and one of the most promising pianists in the country” would garner a name for the small, private Nicholas Senn Hospital. Poor Graces’ tendons in her right wrist were severed, sustained in the terrifying Easter Tornado of Omaha legend.

Seemingly a Wes Anderson imaginary hospital in pink. Postcard of the Nicholas Senn Hospital labeled 1914.

Postcard of the Nicholas Senn Hospital, incorrectly labeled at “Park Avenue & Harney Street.” I was glad to find this image for it displays the 1914 addition was actually on the east side of the original hospital. There is a new north entrance door shown. The reverse side is postmarked December 17, 1914. The address and message are typewritten; the recipient is Mrs. Emily Schlosser, Dodge, Nebr. Publisher: Omaha Public Library.

For perspective, study this cool shot from 1916. Exterior view of First Baptist Church, photographer facing south. Nicholas Senn Hospital seen directly to the south. Those awnings! Creator: Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). Publisher: The Durham Museum. Date: 1916.

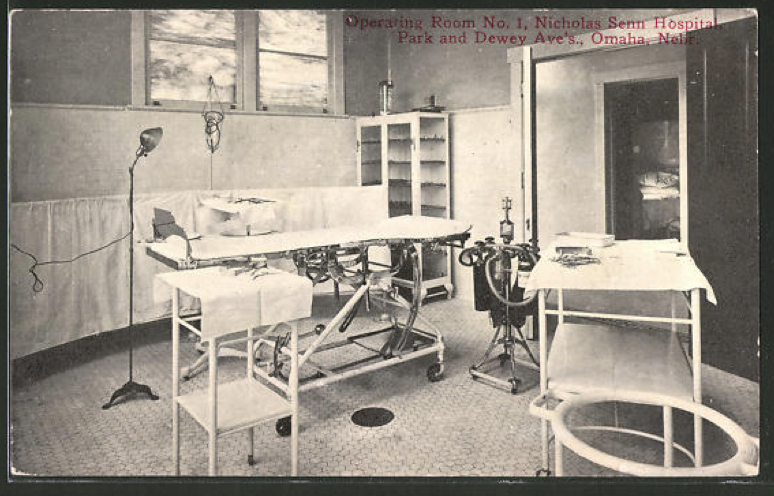

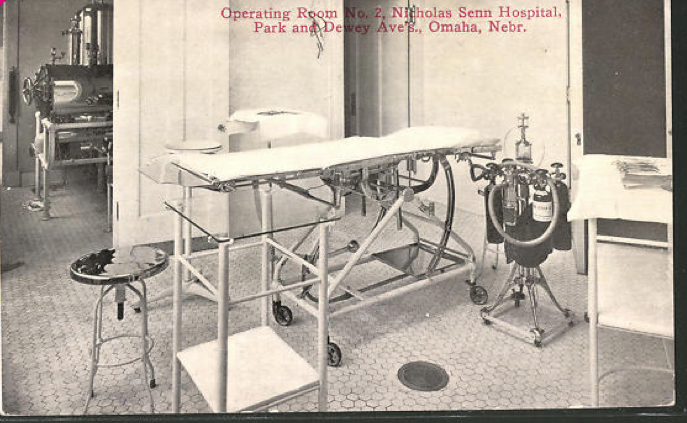

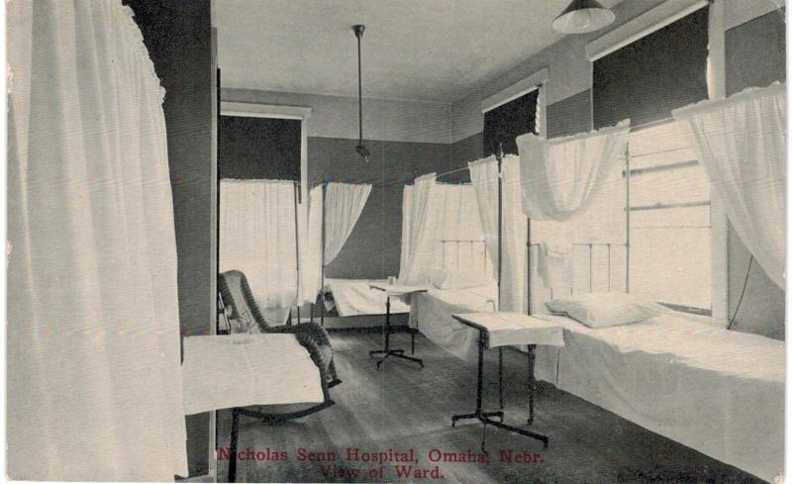

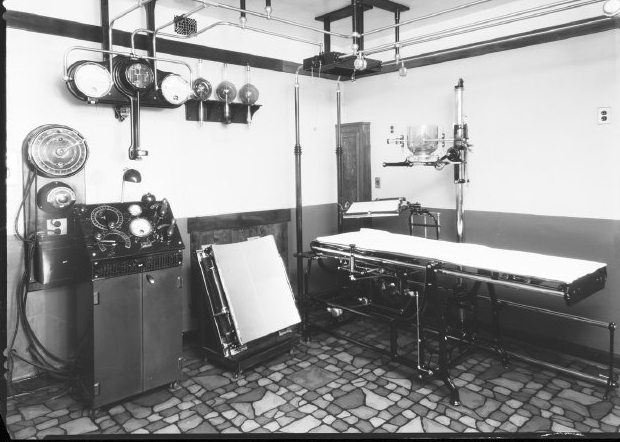

The hospital must have been doing well, for in April of 1914, the Omaha Sunday Bee announced a reception at the Nicholas Senn Hospital. Dr. Condon ‘s newest “four-story addition” was built under the direction of Dr. F. W. Slabaugh and completed at a cost of $100,000, with $50,000 more spent for equipment. “The building is of pressed brick, light colored and mottled with black. It is fire proof, being of interior steel construction, with tile floors throughout, and white enameled woodwork. It is equipped with thirty private rooms and three wards. One of the special features of the Nicholas Senn is the provisions made for the forty regular nurses and those in training. They have their own dormitory in the hospital property. The X-ray room is said to be the most complete of any in the west, equipped with every electrical instrument and piece of apparatus employed in modern surgery.” By the time The Gate City and Douglas County was printed in 1917, the then 60-bed Nicholas Senn “boasted one of the finest x-ray machines in the U.S.”

Assorted Nicholas Senn hospital interiors from postcards found on Ebay. The third one, labeled “View of Ward,” was mailed in 1917.

Although Nicholas Senn Hospital was steadily touted as the innovation of Dr. A. P. Condon, it was his brother, Dr. William Marion Condon, who financed the operation or at least significantly helped get it off the ground. Dr. W. M. was an Omaha dentist and founder of the Creighton College of Dentistry. Twelve years later he would serve as the college’s first dean. Fascinating to find he later gave up dentistry for banking. He was a reputed man of wealth. When the dentist’s wife, Nancy Ottis became ill, the William Condon family moved to California in 1917. That might explain the earlier mentioned warranty deed entry, where William Condon sold the J. I. Redick lots to Albert P. Condon on June 13, 1917.

Dr. Albert Paul Condon

There were many walks around that old hospital I should have liked to stroll with Omaha surgeon, Albert Condon. The information he could have shared about his life, his family, his hospital and the massive home he built would have fascinated me but more than anything I would have liked to take in his personality. For I’ve heard whispers he was rather unusual. (We all are.) I am also terribly interested to know more about his passion for educating nurses, affording opportunity to girls and young women and his steady pattern of patronage to aspiring young people. Born in Indianapolis, Indiana in 1868 to Thomas and Mary Condon, Dr. Condon graduated from Chicago Central College and later Rush Medical School in 1900. We’ve already addressed his fellowship with esteemed surgeon, Nicholas Senn in those years. After studying abroad and then a short stretch in Springfield, Illinois, Albert Condon moved to Omaha in 1902. He was reputedly one of the first Omaha physicians who specialized in general surgery. From a 1927 interview Dr. Condon would reveal that he had studied under Profession Berheim, “the father of modern hypnotism” while he trained in Nancy, France. Bernheim was said to hypnotize 90 percent of his patients. Dr. Condon reflected on his own operations he performed while using hypnotism, which involved the reduction of a fracture of the jaw and a dislocation of the hip. “Hypnotism might be valuable in a case where the patient could not be given ether or gas, but the difficulties involved learning if the patient is susceptible and the loss of time, make its value very small.” By the time of the 1927 interview, hypnotism had largely fallen from surgical practice (probably never a norm) but I found it interesting.

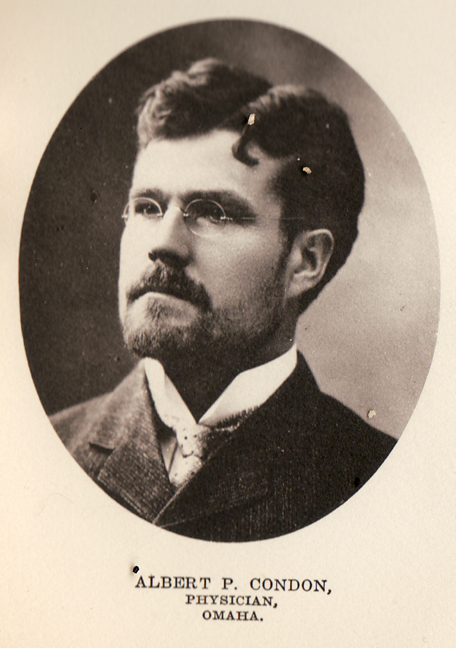

Handsome photo of Albert Condon scanned from my favorite Nebraskans 1854-1904 by Bee Publishing Co. 1904. Part of what I love so much about this book are the historic but contemporary photos. Many photographs in these older books have the people looking so dour. I guess I do enjoy a good severe disposition but more to the point—this particular collection resembles people today. Is it the lighting? Dr. Condon looks like someone I might run into at the Dundee Bank—someone with a very nice jaw and dark curls. But where were we? Ah yes…much like the mentor he named his hospital for, Dr. Condon belonged to the local, state and national medical societies and frequently contributed to medical and surgical literature.

Dr. Lillian

In the summer of 1905 Dr. Condon moved his practice from the New York Life Building to the Bee Building. A marriage certificate, traced through a genealogy site, revealed he married Dr. Lillian Jane Nuckolls that June of 1905 in Clear Creek, Colorado. The license let on that Dr. Nuckolls was living in Omaha, although I would later find she was born in Illinois in 1871 to Thomas Jefferson Nuckolls and Martha Ann Brunk. How exactly Dr. Condon and Dr. Nuckolls met, I am not sure, but Rush Medical School, Illinois and/or the Omaha medical communities might be three strong possibilities. As per usual I was hard pressed to come up with any real details of the female lead in our story. One that I was intrigued by was found in Lillian’s obituary. It stated she was “known to the medical profession as Dr. Lillian Nuckolls.” Curiously, although perhaps telling of the times, her gravestone is engraved “Dr. Lillian Condon.” Oddly the one time I was able to find her name in the papers, other than her obituary, was the auspicious occasion of her Woman’s Club presentation in 1905. This was a women’s social group whereby members could give a talk. Her topic—“Microbes.” I wonder how that went over with the Omaha society ladies? One thing is for sure, Mrs. Condon was a full-fledged doctor, founder, owner and operator of Nicholas Senn Hospital as well as wife and mother, although she was commonly listed in the city directories as “assistant to A. P. Condon.” On that note, if any family member has a photograph of Dr. Lillian Nuckolls that they would be willing to share with this article, we would all appreciate it.

City Directory Clues

Years before the Nicholas Senn Hospital was built, the 1909 Omaha City Directory logged Condon as a “surgeon,” with an office at the 300 Bee Building. Mrs. Condon was listed as “asst to A. P.” I would guess Dr. Condon was granted local hospital privileges allowing him to perform surgeries, possibly with his surgeon’s assistant wife, Dr. Nuckolls.

Dr. Condon had been practicing in the New York Life Insurance Building, later confusingly renamed The Omaha National Bank Building, on the northeast corner of 17th and Farnam Street. Built in 1888, this structure remains one of our most impressive. You can find the perfect view of it while drinking coffee at Culprit Café. On this day in 1922 there was a large American flag hanging over the front entrance with a large statue of an eagle between the two building wings. Creator: Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). Publisher: The Durham Museum. Date: 1922.

Dr. Condon did not have far to move in 1905. I didn’t realize the Omaha Bee Building was one address to the west of the New York Life Insurance Building. The razing of the old Omaha Bee Building—later Woodman of the World Building at 17th and Farnam Street. The Omaha National Bank is on the next block in the old New York Life Building. Creator: Savage, John (1903-1989). Publisher: The Durham Museum. Date: 1966.

The Omaha City Directory auditors entered the Condon residence at 2519 Chicago Street for many years to follow. This address has since fallen off the books. A brief survey of the city map made clear the North Freeway-Interstate 480 ramps now run through this once residential area. I began to dig. 2519 Chicago was built in the late 1800s and was considered a large residence of its day or any day–13 rooms, including a cellar, a laundry room, a vegetable room, a coal room, with large stable and carriage house. W. H. Griffiths, the owner of this massive house, in addition to numerous other properties, apparently operated out the old Karbach Hotel. It would appear that the Condons rented for many years but Griffiths continued to own the house. It later served as an accommodating boarding house for decades to come. Sure enough, in the winter of 1965, a sad little advertisement was run, announcing a “highway vacating sale” of household items. But for their years in the home, the Condons had five children:

Helen (Condon) Greenwalt/Grennwall/Grinewalt Dowd b 1905–

Lillian Marian/Mirian (Condon) Trussel b 1906

Albert P Condon, Jr., (later Dr.) b 1908

Corrine H. (Condon) Gallup Farrell b 1910

Shelley/Shelly Frederick/Fredrick Condon b 1914

I hope you can make sense of my accounting for all of the strange spellings and multiple married names and what not. The Condon children attended Windsor School at 3401 Martha, now defunct.

My Omaha Obsession friend, Diane Hayes, shared this photograph with me. Displayed are three of the Condon children with their “Irish nanny.” I would find this photo is from the Blue Ridge Vintage website: https://blueridgevintage.wordpress.com/2013/11/12/omahas-mermaid-1920s/. The writer of this blog is related by marriage to the Condons. She estimated this photo to be from 1916 but due to the size of the little one, my money’s on 1914.

The Condon Mansion

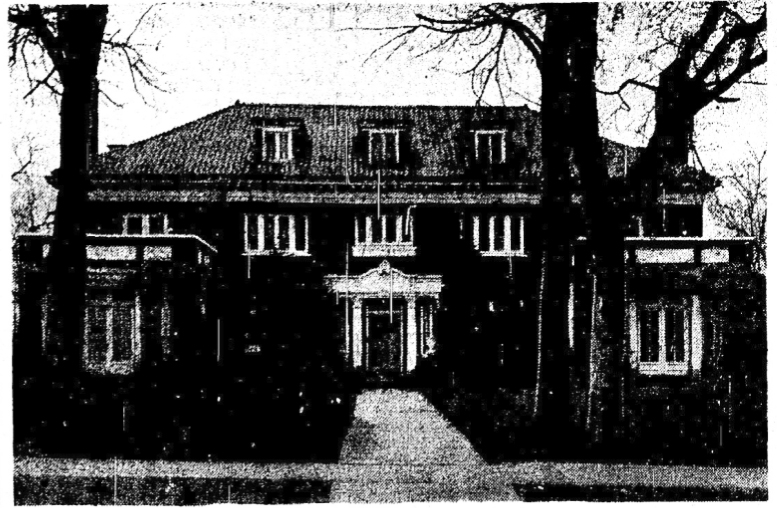

In March of 1916 it was announced for the first time that the Condons had purchased the northeast corner of 37th and Pacific Streets from a Mrs. Martha Stone Adams and planned to build a new residence. “Costing not less than $25,000,” Dr. Condon hoped to have his new home completed in a year. The attractive flat lot faced south toward the Field Club. Interestingly the land had been held in the family of Mrs. Adams for 49 years–the whole block previously owned by Dewey & Stone. I had asked our fellow detectives to jot down The Streets of Omaha clue that Dewey Avenue had been named “in honor of Charles H. Dewey of Dewey & Stone, pioneer Omaha merchants.” And here is where this tip off links up. When the Dewey & Stone pair went out of business, they divided their property, a half going to E. L. Stone. Direct descendant Mrs. Adams had refused to cut up her inherited property. She was waiting for someone to “comport” with those neighboring houses– this stretch of Dewey & Stone Pacific Street proudly known in its day as “The Prettiest Block.” This Condon acquisition represented a fourth of the original Stone parcel at $9,000. When their home was completed, it was assigned the postal address of 3620 Pacific Street. Most all of you with house addictions already know this fine home. I would suggest that the Condon Mansion comported rather nicely.

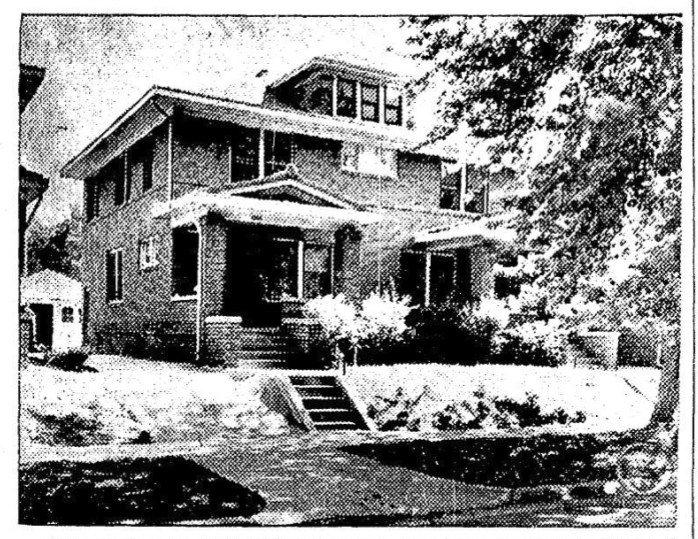

But things did not go smoothly in the upbuild of the new Condon place. Thankfully during the hair pulling trials of their fine mansion, the Condon family lived at 1706 South 32nd Avenue, bordering Hanscom Park, also in the historic Field Club neighborhood. 1706 South 32nd Avenue was built in 1895. A recent sale listed the 3,122 + sq ft single family home as a 5 bedroom, three bath. The 1918 Omaha City Directory exposed the Condons had resided at the 32nd Avenue address longer than expected.

Photo of 1706 South 32nd Avenue borrowed from the Douglas County Assessor’s site. You must do a walk-by to take in its full, divine effect.

The Mansion Plan

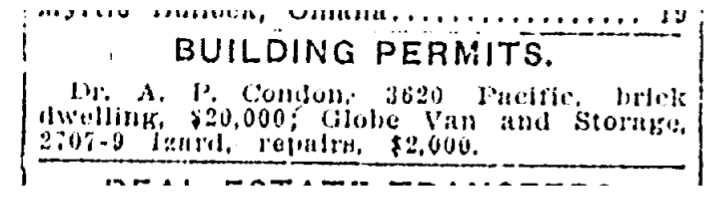

Here we have clue number one. The building permit for 3620 Pacific Street from July of 1917, a while after Dr. Condon’s predicted build date. But things happen and plans change—We get it.

Building permit from July 1917. OWH. Image borrowed from the OWH archives.

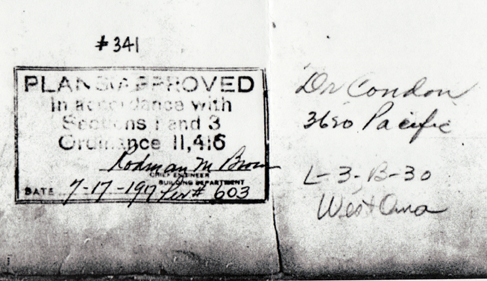

Exhibit two: stamp from the building department on July 17, 1917. At this same time the architect (no name listed on the plans?) had his plans approved by the city. What follows shows an impressive home, with many quirks and family-specific intentional details.

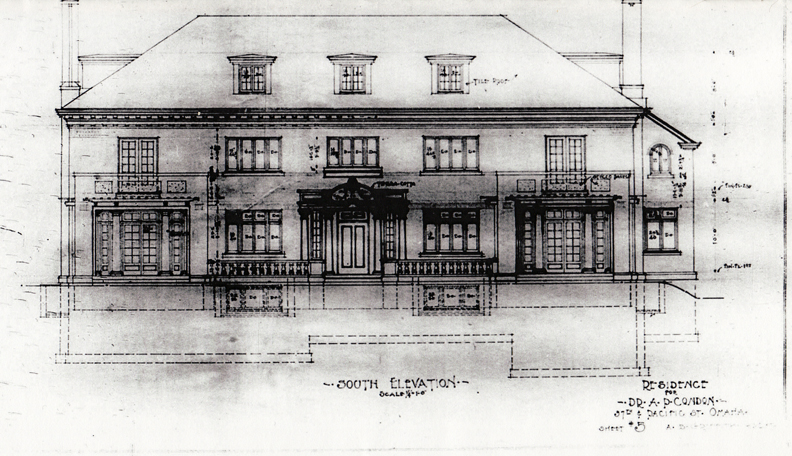

Scan of the architect’s drawing. South elevation. Formal “front” of home at 3620 Pacific. 1917 design.

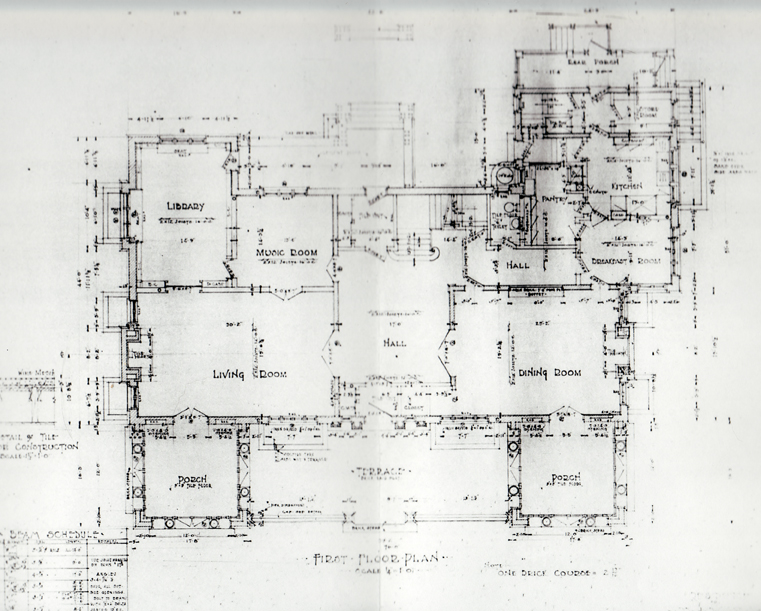

Scrumptious architectural first floor plans. Magnify!

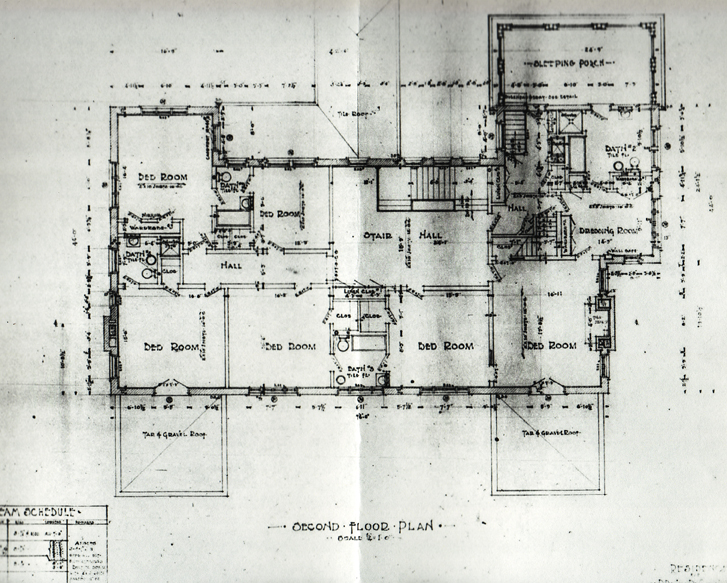

Second Floor plans.

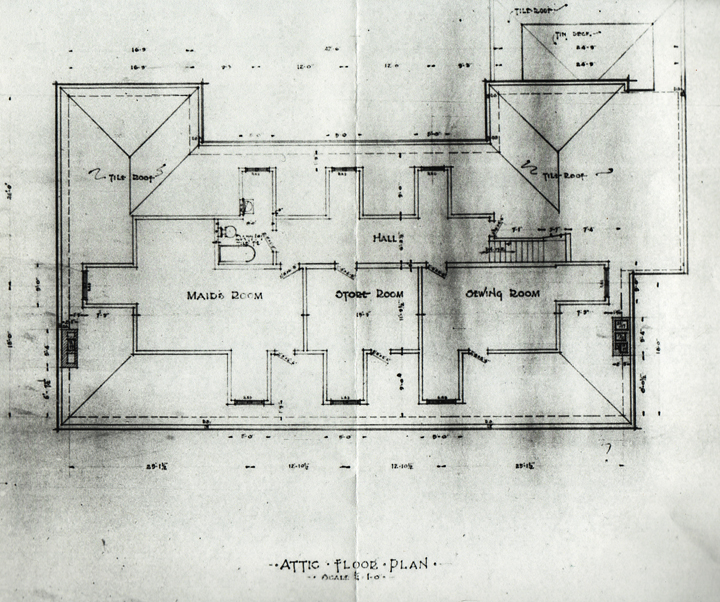

Attic plans. I do love my servants’ quarters. Note the “sewing room.” I found more servants’ quarters in the garage-carriage house. I did not include that scan but the carriage house is pretty splendid. Another garage was added to the property later.

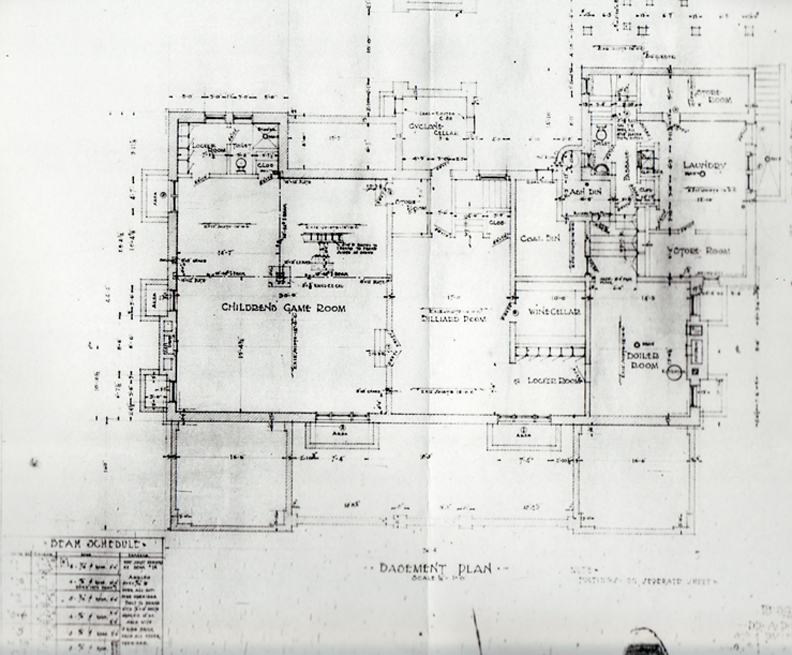

Ooooh the Basement Plans. Would love to have seen photographs of this basement—obviously a gathering place. At least for the Condon children. Note the massive “Children’s Game Room” complete with locker room and shower; “Billiard Room,” with its own locker room; wine cellar; coal bin; cyclone cellar, additional store rooms and a large laundry room. Please linger on this Children’s Game room with locker and shower. This is an area of the house surrounded in whisper to be discussed later.

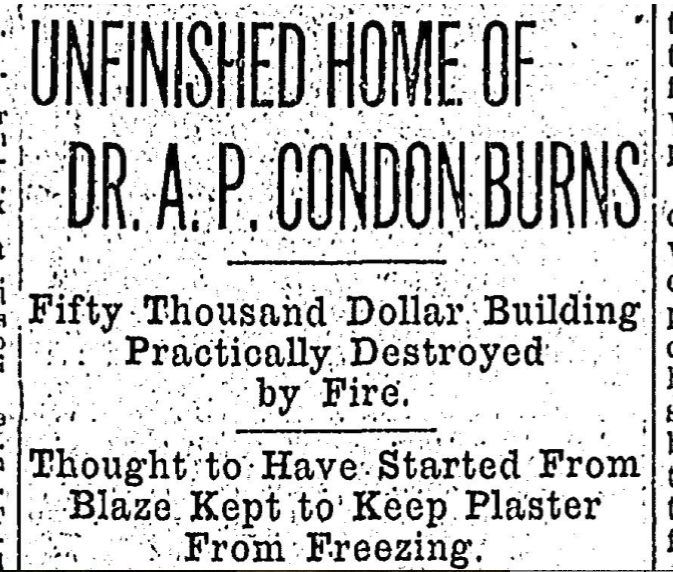

On December 15, 1917 the World-Herald reported that Dr. Condon’s Pacific Street home was “practically destroyed” in a fire. Apparently the yet finished home was started ablaze by a fire “thought to be keeping the plaster warm,” a practice I was not aware of. The neighbors discovered the blaze at 9:17 pm. “The night watchman could not be located last night.” The home, valued at $50,000, “was in process of construction and would not be completed until some time in April.” It was labeled “practically gutted.” The sickening article also mentioned nearby 1004 South 37th Street was damaged after debris was carried by the wind and set fire to the roof. The heartache.

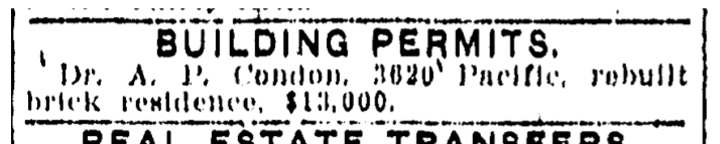

Perfect Clue: By January 3, 1918 the Condon home had another building permit filed with the city. The home was being rebuilt.

The Mystery Architect

I would scour another favorite book, An Inventory of Historic Omaha Buildings, prepared by Landmarks Inc. and Landmarks Heritage Preservation Commission in 1980 and of course they included the wonderful 3620 Pacific in their survey. I was so thankful their registry noted the architect as “A. Griffith” with a completion date of July 17, 1917. They were most likely going off of the date on the architectural plans. There was an additional building noted, perhaps the carriage house, listed as Griffith-designed. By January 2 of 1918 (the rebuild), Griffith was listed as architect and builder. Although we now know (from the above clue) that was the date that the second building permit was filed. I would survey the Nebraska State Historical Society site and found architect Archibald B. Griffith has only two projects listed– one is the gorgeous Condon residence. The Billion Graves site logged Archibald Bulfin Griffith born in 1888 and died in 1965.

Photo of Archibald “Arch” and Mary Griffith borrowed from Find a Grave. Photo added by Jason Dennis on May 29 of 2010.

Mystery Connection—our architect, Archibald Bulfin Griffith and his wife, Mary Louise McClenathan Griffith would name their first son, Paul Condon Griffith. Born in 1919, I assumed baby Paul was named in honor of the Condon doctors but I did think it was odd to name a child after a client. Serendipitously (or planfully) Paul Condon Griffith would go on to become a well-reputed pathologist in Seattle. This sent me on a crazy woman path to find the Griffith-Condon connection. I include my findings, of which I did not write. This is quoted directly from Find A Grave. Although not explained, exactly, this appears to be from the 2006 oral history of Archibald Griffith’s oldest child, his daughter, Adrienne Griffith Birge. Archibald, apparently called “Arch,” attained his architecture degree from the Armour Institute of Technology in Chicago in 1915, “not on the dime of his (Irish) parents, but on the dime of a doctor from Omaha, Albert Condon, who was patronizing his future wife also. Arch would later design the doctor’s mansion, which still stands…Arch was a Mason and could best be described as an agnostic religiously. He smoked, drank, gambled on horse and dog races, and ate steak every night. Not surprisingly, he eventually had a heart attack, which happened about a month before his actual death. He and his wife are buried less than 200 feet from his parents. They raised their four children in a house he designed himself. It was at 60th and Leavenworth, a brand new development at the time, and Arch designed several houses on the block.” Daughter Adrienne also mentioned her father was a longtime government engineer. When I looked into Arch’s wife’s genealogy it would appear that Mary McClenathan ran away from her family home in Iowa at the age of fifteen and “boarded with an Omaha doctor who patronized many people and became a nurse at a hospital he ran. She remained close to her doctor patron until his death.” It became clear that the Dr. Condon and Dr. Nuckolls meant a lot to the Griffith couple and that Paul Condon Griffith was most definitely named in thanks for the Condon patronage. How grateful I was that someone entered Adrienne Griffith Birge’s memoirs on the internet.

The more and more I dug, I just found more interweaving clues, such as the Condon & Griffith real estate team. I believe Griffith designed and built the “Colonial Bungalows” and as a duo of Dr. Condon and Arch Griffith, they marketed the homes “on 59th Street, just south of Leavenworth.” The Arch Griffith family lived at 820 South 59th Street, an address that no longer exists but the whole block remains intact. This is one of the best blocks around. You must drive from Leavenworth to Mason Street on South 59th Street. These are the homes that his daughter made mention of, I am just sure of it.

842 South 59th Street, built in 1921, is in the bungalow style. Dr. Condon sold this home, most likely a “rental” investment, in 1936. Congruent with the architectural feel of this great little pocket of Aksarben-Elmwood Park, I’ve got to assume since Condon owned it since its construction, that 842 South 59th was one of the Condon & Griffith-designed homes. Love this House and her little winking eye! 1936. OWH archives.

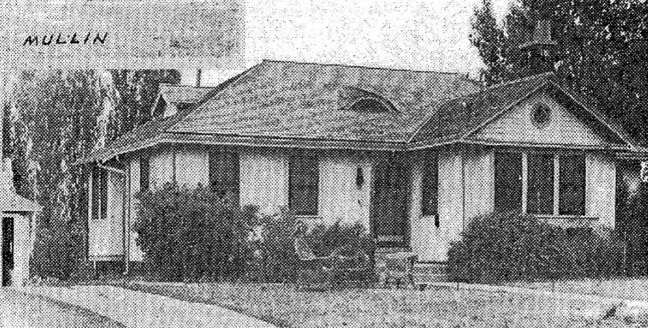

Clues to 3620 Pacific

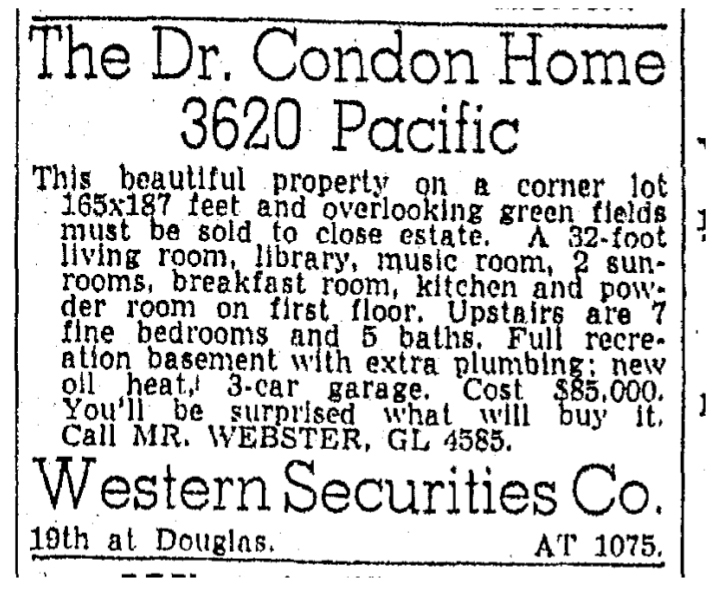

Although oft recorded as being completed in 1921, I would find the Condons living in their 3620 Pacific Street mansion by at least 1919. The expansive dwelling faced south, the Field Club. Early on it was said to border open fields, which we know became a manicured park like golf course. The Condon property itself, in time, was also highly landscaped. Cost of its construction was estimated at 85 thousand dollars, although some would continue to quote its original cost, possibly from the initial building permit, at “twenty thousand dollars.” I have read it contained “19 luxuriously finished rooms and seven baths.” Its elaborate construction was widely marveled for its “nine bedrooms, two sunrooms, large play room, billiard room and wine cellar in the basement. Three-stall garage. There are three fireplaces, in the living room, dining room and the master bedrooms.” When the home was last sold in 2016, it was stated to have 10,000+ sqft. I am not sure if this was the original square footage in 1919. And now I will assert the obvious and possibly in bad form. Those early Nicholas Senn years must have been good to the Condons, for 3620 Pacific was a goodly sight the likes of which Omaha has never seen. She remains one large, dignified gal. While massive, she is of restrained and handsome design. Balanced. I suppose more of a Queen Bee of Field Club…or is she a Matron? (We believe in the anthropomorphism of houses around these parts. Embrace it.) More to the point when 3620 Pacific was completed (born)– sitting at over 10,000 square feet more or less, with three stories and a full finished basement (rare for 1919), in addition to those defining characteristics of luxury, at least in Omaha, lands a home in the Mansion Category and ownership was typically reserved for titans of business, the corporate elite or those of inherited wealth. Did the Condon-Nuckolls have other means? Surgeons, although modern gods in our society, are working medical professionals and we historically did not see a house of this size constructed for physicians in Omaha. Perhaps 3620 Pacific embodied the difference between what a doctor could attain–a medical practice vs. proprietorship of private hospital business. There is also the matter of taste that we cannot discount. Drs. Albert and Lillian had a particular aesthetic view, which possibly explains all of this peculiar beauty. Initial probing experiments were conducted to no avail.

The exterior of the Dr. A. P. Condon home, located at 3620 Pacific Street. Creator: Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). Publisher: The Durham Museum. Date: 1919.

A car parked in the street in front of a house at 3620 Pacific Street. SWANKY. Creator: Bostwick, Louis (1868-1943) and Frohardt, Homer (1885-1972). Publisher: The Durham Museum. Date: 1922. A year after this photo was taken, young Albert Condon, then 16, exchanged shots with a burglar who came to prowl around the family mansion. “Both shots went wild and the burglar escaped.”

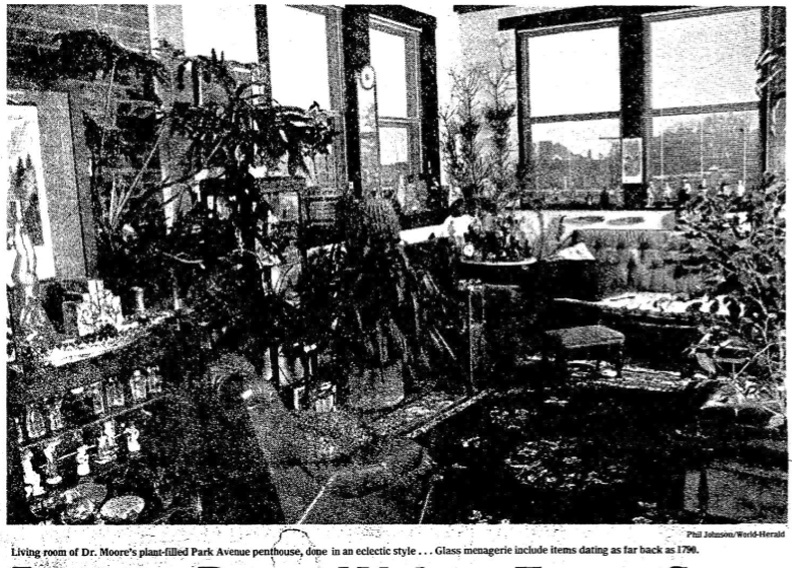

As we continue our investigation through the Condon family history and their Nicholas Senn Hospital, the forthcoming dates will fall into place. I don’t want our years to become all gobbledygooky and only mention these timeline hints as we fixate on the 3620 Pacific residence. Or maybe it is neurotic…you decide, as always. Hopefully you understand my process in these matters. By 1933 the Condons were soliciting lodgers, for 3620 Pacific offered up “three-room suite and single rooms for rent.” We have seen this custom previously in our investigations and have observed large homes graciously adapting their glorious interiors in these thin years of the Great Depression—most evidently for financial reasons. By 1935 the whole house was on the market but only advertised six bedrooms and four baths. Had it been reconfigured into a duplex? I would have to tiptoe down to the W. Dale Clark Library for supplemental info. Drs. Albert and Lillian did indeed live at 3630 Pacific in 1935 but by 1936 they were residing in the Nicholas Senn Hospital. I assumed the Condons’ quarters had been built for doctors working long hours but as my mound of research continued I would find there were other possible apartments built within those hospital walls. When J. E. Riley’s wife went missing back in 1915, it was revealed Riley was an engineer at the Nicholas Senn and the couple lived at the hospital. Because you need to know, Dora Walling Riley was assumed to have drowned herself in Keg Creek in Glenwood, Iowa, despondent over the death of her mother from the previous winter. In 1919 burglars had held up the two Nicholas Senn caretakers, Jens Knudsh and Anton P. Jenson at gunpoint. The caretakers were “sleeping in their room in the basement.” Surprisingly the thieves ransacked three trunks of clothes of the nurses, making off with a silk dress, “a broadcloth suit and street clothes” in addition to Jenson’s watch and $56. The burglars had broken lights in the basement and cut hospital telephone wires, leading suspicion that there had been a larger plan in the works. But where were we? To put a finer point on it, the 1936 Omaha City Directory listed 3620 Pacific as “vacant.” From then on there were no listings of Dr. Condon and Dr. Nuckolls’ whereabouts, which mystified…until a chance encounter with a 1933 article. The article laid out that the couple’s son, also named Albert, had a trained hunting dog, named Juno. Juno was purportedly shot in the leg “at the Condon family farm north of Florence—either by a spent bullet or by someone with malicious intent.” Dr. A. P. Condon operated on Juno at the Nicholas Senn hospital. “Juno occupies a special room it the hospital basement and will be able to leave soon.” Fascinating, really…but from this, I would learn the Condons had a couple of properties out of town, to include their holiday home on Lake Manawa, in addition to homes in the city, which I figured were rentals. It began to make sense that they still operated their hospital but didn’t necessarily live in Omaha proper. At the time of 3620 Pacific’s 1940 sale to local insurance man, Lawrence E. Johnson, “as an investment,” the Arthur C. Storz family had been renting the Condon Mansion. I would verify this using the city directories and found the Storzes rented from 1937-1940. Because of the sale, this family was thought to take up quarters at the Storz “home place,” the mansion of Gottlieb Storz at 3708 Farnam.For more on this house, please read I Have a Ballroom in my House.

February 1940 listing. Happy for the descriptors. OWH archives.

3620 Pacific is sold. Its 1940 sales price was not revealed. OWH gloomy and wonderful photo from April 28, 1940.

From what I could sew together, Johnson was suspicioned to formally split 3620 Pacific into a duplex in this April of 1940 time period. The newspaper would lead me to believe that by 1941 the home had been listed as separate rental apartments but the City Directory showed the house in the Lawrence E. and Albert W. Johnson names only. Clearly by the late 40s-early 50s, the Condon mansion had been broken up into 6-7 distinct apartments. They have been rental flats ever since.

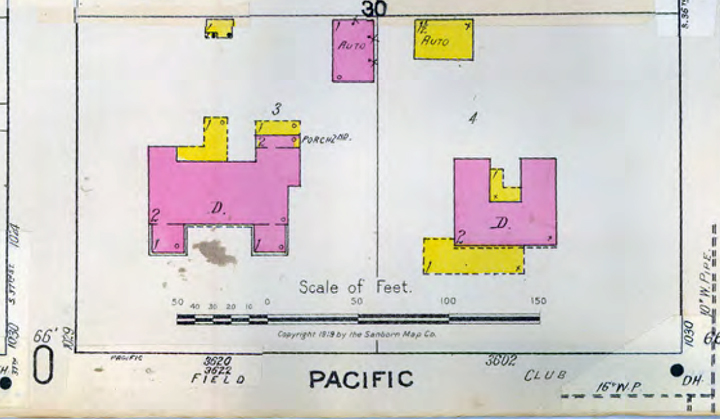

Trina Westman is now an architect at Alley Poyner Macchietto Architecture but when My Omaha Obsession first encountered her, Ms. Westman was employed with the Omaha Planning Department. So very long ago she unearthed the Sanborn Maps from the Field Club area. I am not 100% of the year of this particular map but this is a detail of the 3620 Pacific footprint and its beautiful neighbor to the east, 3602 Pacific. The pink “AUTO” building behind the Condon Mansion was the original carriage house (photo upcoming). The little yellow building displaying a “1” behind the house was an additional garage, I believe added in the 1940s. If you squint, you can see that 3620 also had an additional address added—3622 Pacific. (This is common with the Sanborn Maps—presumably made to be altered over time.) Of course you know I obsessively spun down that cobwebbed hole with my dull potato peeler. 3622 Pacific was most definitely functioning within the Condon property site, likely as a portion of the duplex. I first found it in the papers and also the city directory in 1942. A scouring of the 1942-1962 Omaha City Directories revealed the large home’s postal address actually changed to 3618-22 Pacific, apartments A-F in 1952. So from those clues, I would date this Sanborn Map from 1942-1952. Confusing or delicious? Image magnified from the original Sanborn Maps of the Field Club Neighborhood.

At that time, Detective Westman was also able to dig up these Planning Department survey photos of 3620 Pacific for me and I’ve had them filed away all these years just waiting for today. I believe these images are from the 1970-1985 period. I am not sure of the photographer to credit. I thank you, Trina Westman!

Youthful Detour

When the Condon Mansion was for sale years ago (2016, I believe), I acquired Architect Griffith’s original floor plans. This was a real delight to me, as I had been in the house a handful of times in the late 1980s. I had a trio of girlfriends living in an apartment on the second floor. Like a small band of hoaxers, they were by far the youngest tenants, whereas all of the other renters appeared to have real adult lives and careers to match. At the time, none of us had seen dignified accommodations quite like it—a stately brick mansion overlooking a golf course. It was all so glamorous! Just walking across the formal terrace up to the front door stole my breath away. The entrance hall. The windows. I still remember tiptoeing up the giant, beautiful staircase to their apartment door. I believe there was a little sitting area outside their door. My girlfriend, Kristin Crouchley Burke in particular was the teen queen of décor, (still is, but we are no longer kids), and of astoundingly good taste for her age. More from the Edith Wharton school than the fruit and milk crate aesthetic the rest of subscribed to. What theater she could create with accent lamps and furniture placement! The girls’ living room seemed so grand. The décor was of a posh style, at least to my young eyes, seemingly harmonious with the architecture. Kristin just reminded me her “posh” living room was actually furnished with her parents’ castoffs–avocado green 1970’s high wingback chairs! She reminisced about the beautiful hardwood floors, large windows, incredible woodwork and crown moulding throughout. There were French doors leading out onto a black tar roof “deck,” that seemed a real luxury to Kristin, although she feared she might fall through with each step. I can now see, this patio must have been atop the downstair neighbors’ sunroom. The girls’ dreamlike living room had a fireplace, which impressed me greatly. Their glorious mantel held a number of candles, to memory, and a framed photograph of Oliver North, an Of The Times conversation-piece contribution by another of the roomies. I now recognize this “living room” must have originally been the master bedroom or a fine sitting room with its own fireplace. I remember trying to imagine the mansion as a single-family home and it gave me great shivers of pleasure. I guess it still does.

The Swimming Pool Rumors

Somewhere along the line, the Condon Mansion lore expanded to include tales of a swimming pool in the basement. This was most intriguing! My Omaha Obsession detective, Diane Hayes, currently lives in the mansion as a renter. She wrote me years ago about coming over to investigate and in the exchange mentioned the home “at one time had a swimming pool in the basement.” I have another girlfriend, Megan Malone, who rented for two years at the Condon Mansion a while back. She shared that she too had heard the swimming pool story. “Whoever built it put an Olympic training pool in the basement because his daughter had interest in swimming.” (We will get into the swimming daughters). Megan estimated the Condon mansion basement had oddly high ceilings, almost 16 to 20-foot high ceilings, to her recollection, so the rumor seemed plausible to her. When I pressed to see if she had actually seen signs of a pool, Megan said she never saw the pool remnants. She remembered touring the basement apartment when she was looking to rent. “The realtor loved the building and just showed me around. I was under the impression it had long been converted into an apartment.” In different apartment rental listings for 3620 Pacific Street one will find these clues and tasty phrasing: “Unit G is on the lower level of the home and was once the indoor pool and gymnasium! Makes for ornate windows, high ceilings, and one of a kind originality!”

I am not so sure of this mysterious pool storyline, however, to date, I have no hard evidence that pool did not exist in the Condon basement either. Weirder things have happened and not been documented by the papers. Here is what we do have: The original floorplans did not include a pool, however there was a “Billiards Room”—perhaps mistaken by a realtor or described through word of mouth as a “pool room.” Those floorplans did include a “Children’s Game Room” with an adjacent locker room with shower. We’ve got solid evidence of Dr. Condon building a swimming pool and solid evidence of where the Condon girls did swim regularly, upcoming. Perhaps the simultaneous building of that Condon pool was misconstrued over the years? There was no mention of the Condon private basement pool in any historic information I could find, to include the 1940 sale and the 1983 Field Club tour of homes of which the 3620 Pacific home was included. But the 1940 advertisement mentioned a “full recreation room with extra plumbing” in the basement. If the private swimming pool was added to the home originally but had not made it in the floorplans, it would be a splendid curiosity. The mansions of Long Island’s Gold Coast were filled with private indoor pools, some in basements that could be covered at a moment’s notice with hydraulic flooring for parties and such. So it isn’t the basement pool idea that I am leery of. Now I’m pretty ignorant to these matters but hear me out—if an indoor basement swimming pool was installed at a later date, what would this have meant engineering wise? The Condon Mansion certainly had the ceiling height and underground space for it but I am wondering about the filtration and the ventilation of an enclosed basement area in those early days structurally speaking, considering the family home in the floor above. Stepfather of Miss Cassette, an engineer through and through, was consulted on this gnawing conundrum. He suggested that digging into the ground beneath the Condon Mansion would not be the concern, rather structural containment is typically the issue—the coping around the pool, the cement around the pool within the walls of the home. He also talked at length (you know how engineers are) about what measures would have been taken to ensure there were appropriate sewer lines for water drainage, if it was indeed after the original construction. He too was concerned for the ventilation if a pool was added at a later date, in addition to potential wood damage incurred by water or steam in this finished basement. Off handedly he suggested that this Condon pool may have been an above ground tank—something I had not considered but perhaps, was much more manageable than I was thinking of. For what it’s worth, my friends renting in the 1980s had not heard of this basement pool, although that was a lifetime ago and we can’t remember everything. My girlfriend did describe the 80s basement as being a dank, dark, and scary place that she wouldn’t go to by herself when she had to make trips down there. For storage or laundry? Omaha is a wonderful and mysterious place and I just know someone is sitting on information regarding the Condon Mansion basement pool. I hope that they will share with us!

Nicholas Senn Hospital Makes Headlines

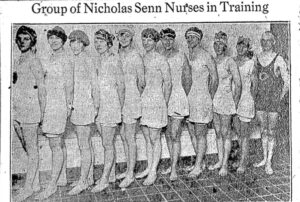

Okay…so, for those of us still huddled here, let’s check in with our notes. I will effect the necessary re-introductions as my assistant, Mr. Cross, serves a very mild cocktail to those who are interested. Obviously I have been drinking iced coffee throughout our tour and am highly vibrational at this point. I am jittering in the clouds. No matter. Let’s refresh: The Nicholas Senn Hospital opened its doors in 1912. From what I could make out, the hospital was reputed and fairly conventional in its early years, although its growing nurses training was a real feather in their cap. The Condon Mansion was completed by at least 1919. This was also the year that Nicholas Senn became known for another offering, an unforeseen advantage and one that would dovetail with their nurses’ program. I lay particular emphasize on this year to arouse a frenzy of curiosity.

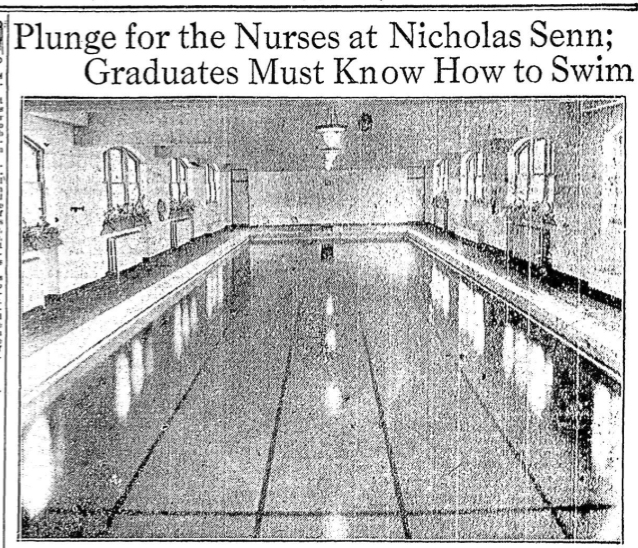

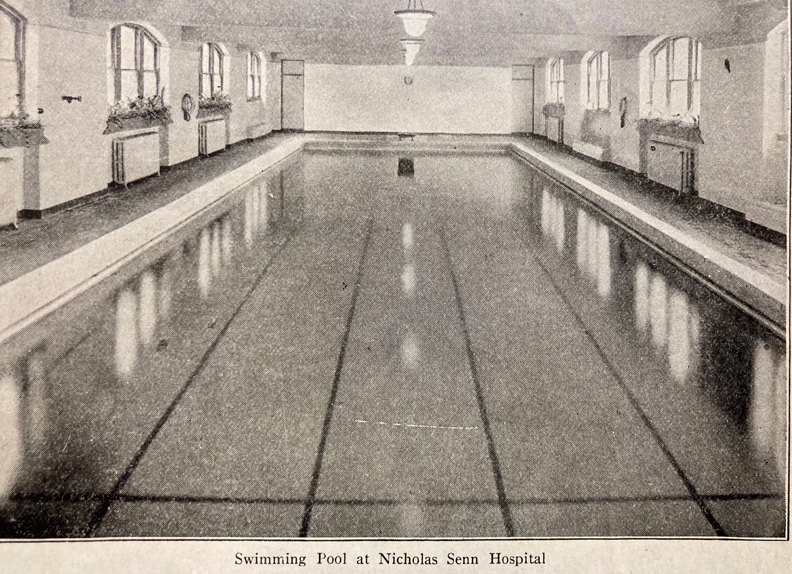

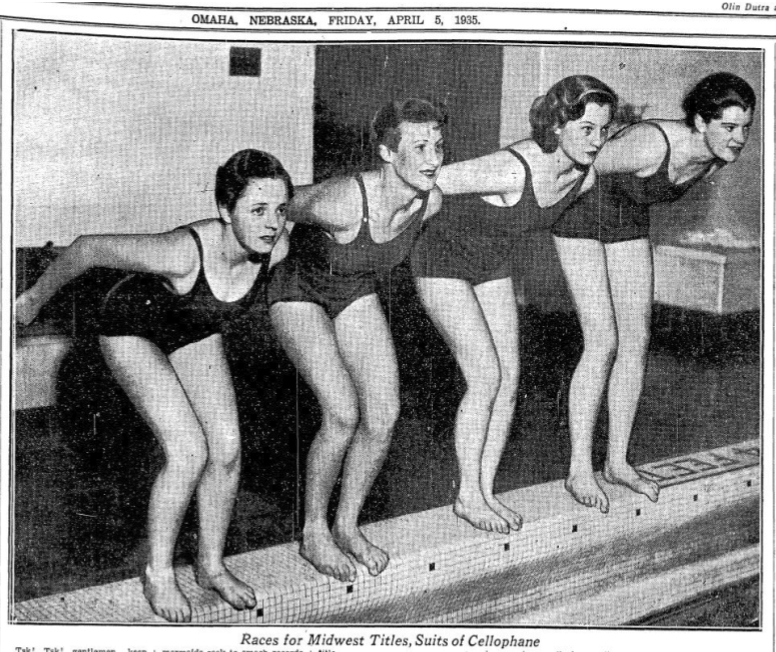

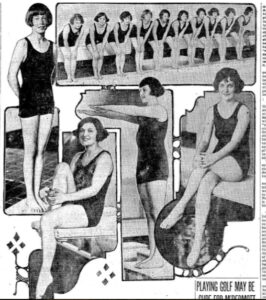

In May of 1919 a new wing of the hospital was opened and was said “to fit in with the older part of the building, providing room for the comforts as well as the complicated medical appliances.” I believe this was the southern wing. By June of 1919 the Nicholas Senn Hospital publicly announced they had built a swimming pool.

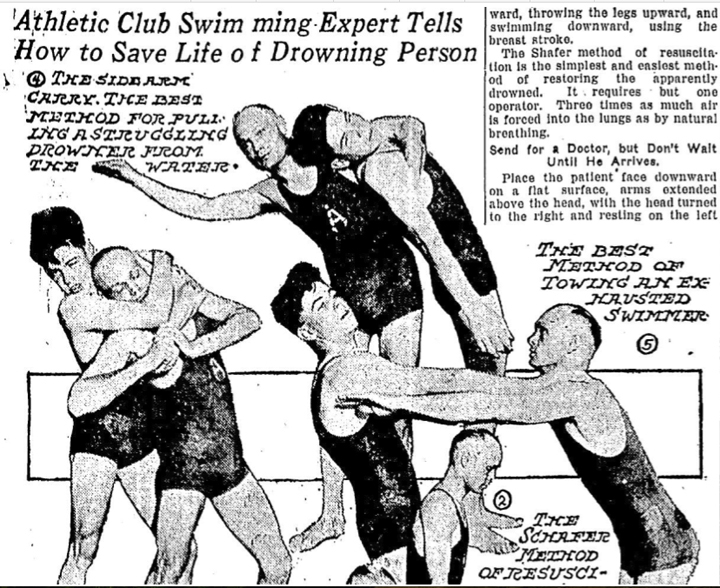

I would dig and dig to find the interesting news that Dr. Condon’s protégé, Architect Archibald Griffith, had designed the Nicholas Senn swimming pool in addition to the Condons’ Field Club mansion. Numerous sources made mention that Condon spent $25,000 in equipping the pool, also called an indoor tank, in this 1919 expansion. Hospital pools were sometimes found decades later across America in the promotion of health and wellness for patients but in 1919 this hospital pool concept was thought unusual, at least by Midwestern standards. To put this hospital “natatorium,” as they were called, into perspective, I would do some additional surveying. “Plunges” were few and far between in this time. It really wasn’t until the 1930s that nicer hotels even began to offer swimming pools to their guests. The late 1920s through the 1930s revealed more municipal pools springing up but women and men swam on different days. The Nicholas Senn Pool was a marvel. Even stranger still (and we do embrace strange around here), Dr. Condon wanted the pool for his nurses’ program, not for patient use. “Graduates must know how to swim. Every graduate nurse must pass in swimming as well as her studies and experience in order to get a diploma.” I was fascinated.

June 1919. OWH archive. Behold.

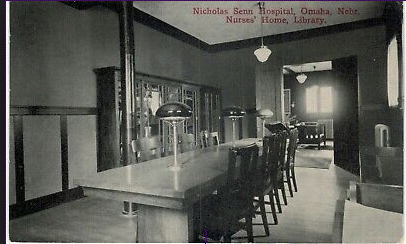

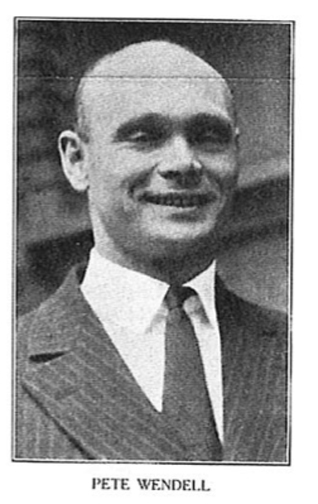

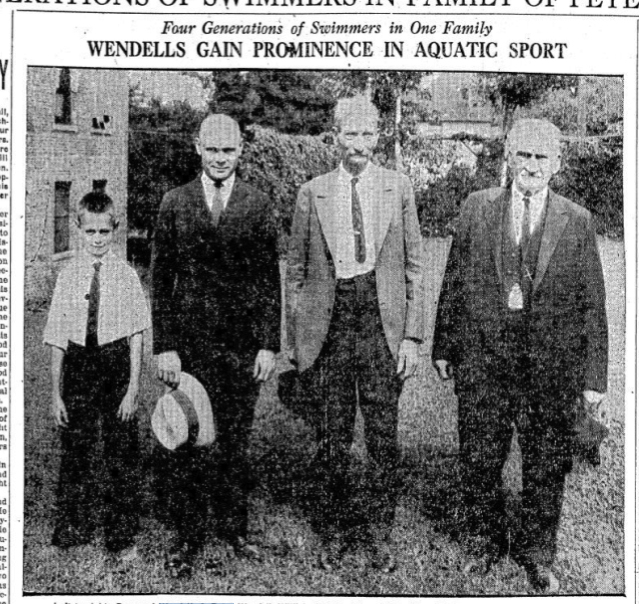

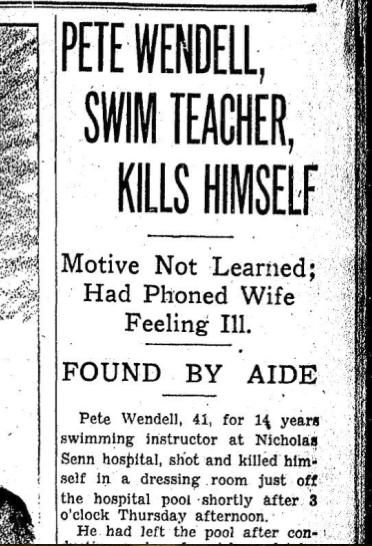

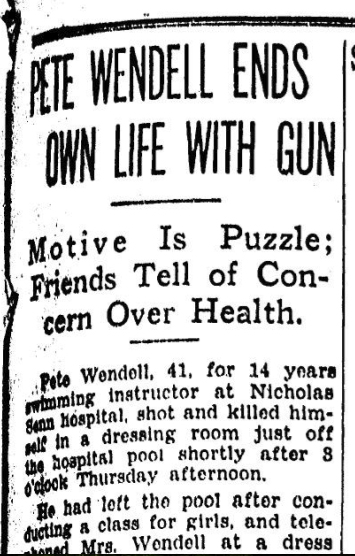

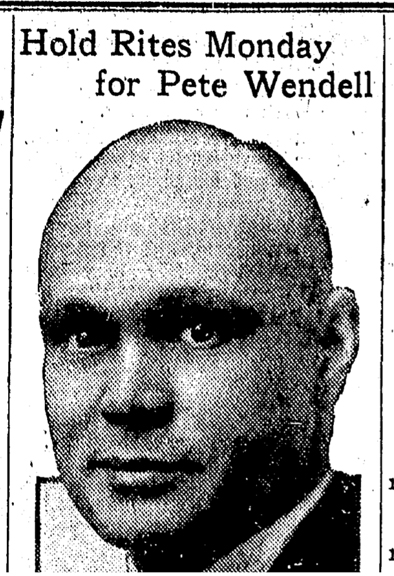

Condon’s program had fifty nursing students who lived on site, while they studied and worked in the hospital gaining on the job experience. This arrangement was something Father of Miss Cassette has said was commonplace by the 1960s. The Nicholas Senn nurses’ quarters were said to feature a gymnasium, tennis, show baths, library (see the darkly intriguing postcard below) and rest rooms but the “big hit with the nurses” was the new pool—described as almost identical to the one at the Omaha Athletic Club, offering the same width but fifteen feet shorter in length. “Three times a week Pete Wendell, Athletic Club waternaut, conducts swimming classes there. The pool is lit up at night with bulbs under the water. It is completely renovated every twenty-four hours with violet ray and filter, making the water clear as glass. ‘Dr. Condon put this pool in because the nurses went so often to the YWCA and talked about the pool there so much,’ said Dr. C. H. Newell. ‘They get a lot of good out of it and this is part of the equipment plan which we believe will make the nurses more comfortable and contented and necessarily more efficient. Tennis courts are now being built. Entirely aside from its scientific and medical equipment, it is a first class, up to date home where cleanliness and comfort for the nurses as well as the inmates are made easy.’”

Great Nicholas Senn Nurses’ Home Library postcard.

In trying to piece together what prompted Dr. Condon’s pioneering aquatic philosophy, I would later find that he had unfortunately witnessed the 1918 drowning of Miss Betty Elkins, a schoolteacher. Condon apparently tried every method to revive her. Examination would later reveal that her lungs were not filled with water, but that she had died of heart trouble. I cannot be sure if this event contributed in part to his conviction. Again this is just my obsessive folly in trying to make connections for my own understanding. One of the many things I would have asked the good doctor if I could have spent time with him. By all accounts Dr. Condon seemed to care deeply for his nurses’ emotional and physical well being. If one were “down or moody,” he was known to rearrange their shift work and send them out for fresh air or “to play.” He encouraged them to play tennis and be active in the out of doors. (As an aside: These healthy activities were of high importance, however, I did find there was an equally high-minded prominence placed on morality and proper ladylike behavior. For instance, in 1921, shockingly, twelve Nicholas Senn student nurse were “discharged for alleged infraction of hospital rules.” The nurses broke the rules by stealing out at night, taking automobile rides and attending dances!) Interestingly the Condon family would organize musicales and performances for their nurses. I would also marvel at Dr. Condon’s same ground-breaking whole health doctrine animated in his young daughters’ athleticism. Perhaps inseparably, Dr. Albert Condon’s dear brother, the wealthy dentist turned banker, who helped launch the Nicholas Senn Hospital, Dr. William Condon, drowned in 1920 after being caught in a rip tide while “surf bathing” with his daughter, Nora and brother in law at Condon’s home of Long Beach, California. The ill-fated swim in the Pacific Ocean no doubt confirmed our Dr. Condon’s passion for aquatic lessons when it became evident young Nora Condon “escaped death as a result of being a good swimmer.”

Women and Swimming

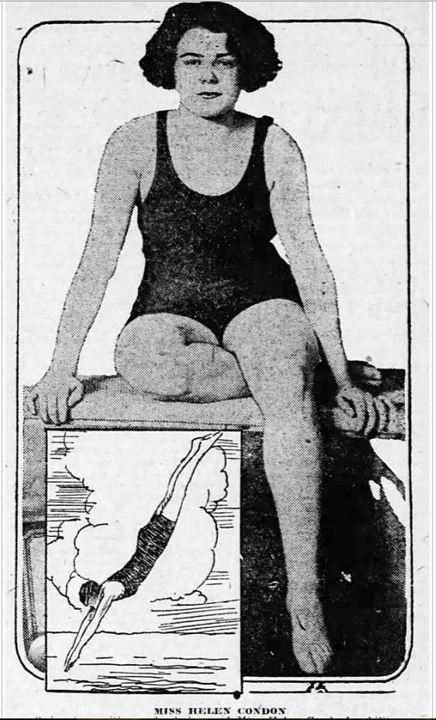

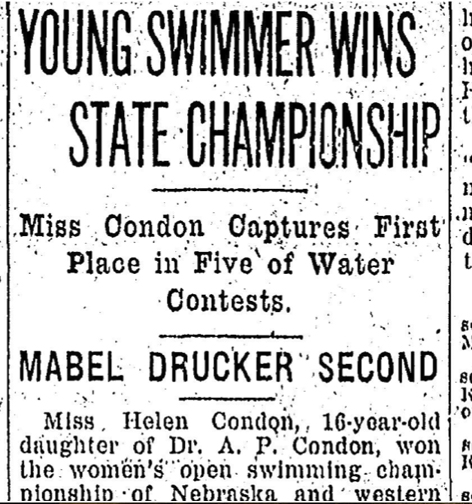

The large tiled, modern pool was initially built for the use of the Nicholas Senn nurses but by 1920 it was decided the private pool would be opened to the public. Pete Wendell, the swimming instructor of the hospital pool, along with Helen Condon, the daughter of Drs. Condon and Nuckholls, and “a corps of nurses,” began taking in aquatic pupils. The hospital offered free swimming school for girls between 14 and 18 in June of 1921. Dr. Condon sponsored the school. The lessons would expand to mothers and their children. Condon would often share the pool with other female organizations, such as Brownell Hall girls school. I thought it odd that so much focus was placed on the nurses, women and girls. Why did the nurses specifically need to learn to swim rather than the medical staff as a whole? When they expanded to the Omaha public, why not teach little boys and adolescent males? I would find hints that Omaha did not have public swimming pool where females could learn to swim, although, apparently, the nurses had been swimming at the YWCA, per their report. There were also a handful of private clubs where I discovered women had special swimming hours. The Nicholas Senn tank appeared to fill a need in town.